September 2012 Biblical Studies Carnival

Tim Bulkeley has the latest “Biblical Studies Carnival” up and links to a number of interesting articles. We’d like to thank him for referring there to us here as “the kind people at BLT.”

But we also are grateful to Tim for introducing, in the intro of his post “September: Spring comes to Biblical Blogaria,” several new bloggers. Yes, it’s Spring, and so he starts:

Among the first signs of spring we expect the first of the season’s crop of new blogs, as the northern hemisphere returns to work after their long lazy summer. Among the first to appear this spring The Jesus Blog, features Anthony Le Donne and Chris Keith. The handsome design includes an array of portraits of the great man (Jesus, I assume, not Ant hony or even Keith). Another from Francesca Stavrakopoulou of the University of Exeter first appeared late in the month, it began with a sort of brief manifesto for the innovative Liberal Arts program Francesca directs. Margaret Mowczko’s New Life (though it is not new) was new to me, she focuses on reading the Bible as a woman and has interesting thoughts on The Portrayal of Women in the Bible and Biblical Inspiration.

I think you’ll notice how he doesn’t only or even mainly feature male bloggers, which is quite refreshing. Nonetheless, it’s not “The End of Men” in the Biblical Studies Carnival by any stretch; and some of us kind people may have to say more on this soon.

You should have your say too; so for the next Carnival (the October 2012 one), we invite you to write and also to nominate the best Biblical Studies posts of next month. We are happy to follow Tim’s hosting and will be highlighting your posts in that next carnival here at BLT.

Do go read the rest of the September 2012 Biblical Studies Carnival at Tim’s Sansblogue.

Translation makes us fall in love.

Tomorrow is International Translation Day. Here, then, are “10 Ways Translation Shapes Your Life” as Nataly Kelly has identified them:

10. Translation makes us fall in love.

9. Translation feeds the world.

8. Translation tests our faith.

7. Translation entertains us.

6. Translation fuels the economy.

5. Translation creates jobs.

4. Translation elects world leaders.

3. Translation keeps the peace.

2. Translation prevents terror.

1. Translation saves lives.

Kelly elaborates these actions of translation in her co-written book (with Jost Zetzsche), Found in Translation:

And to give a bit of a pre-view summary, Kelly has written her thought provoking essay (mentioned), “10 Ways Translation Shapes Your Life,” which you can read fully here.

Not Only A Father: not only a book

Tim Bulkeley has written a book. The title is Not Only a Father: Talk of God as Mother in the Bible and Christian Tradition. You can buy it in traditional printed book format

if you are so inclined.

But he has also done some other interesting and perhaps radically innovative things with it.

He’s made it available online – in a format that not only allows but encourages comments to be left and conversations to take place in the margins of the book.

Is this the future of publishing – or at least, of scholarly publishing?

The above is the announcement James F. McGrath made in a blogpost at his blog, Exploring Our Matrix. James there gives his opinion about what this possible “future of publishing” might allow (so go read what he suggests); but he also gives an extra link to Tim’s book (online with the public margin commenting option) and then invites readers to return to the blog to share their comments there.

In more private conversation, Tim has said: “I want to explore how authors and readers can engage more and at greater depth through using online communications.” He calls what he’s doing an “experiment.” And he may be working out a few things before his own public “launch” will be made.

I’ve already begun reading Tim’s book, and I will review it. But note that my review will be right on site, online, at his book, where I’ve written already a few comments. I see another commenter also has already done this as well. This is a bit different from Kindle ebook formats, which does crowd source the most highlighted lines of books in the digital format. Tim’s format allows for overhearing and for participating in conversations with other readers and with the book’s author. Look for more on this here perhaps. And do feel free to leave comments at the blog, to dialogue here about this with us. But do go read (and write) for yourself:

PS: Tim is blogging the next blogger Biblical Studies carnival, and it’s still not too late to send him suggestions for that here –

http://bigbible.org/sansblogue/digital-life/blog/biblical-studies-carnival-warning-notice/

Jesus’ Wife had no PreNup, so he Got Even

This is the gospel according to Donald Trump, Michael Cohen, Jerry Falwell, and Johnny Moore:

Jesus had a wife. (Okay, that’s another gospel too because we all assume she didn’t die and, therefore, he cannot be a widower.) He never intended to divorce her, but she had a good lawyer. The point is he never got her to sign a prenuptial agreement. Jesus’s wife had no prenup. So, when the marriage dissolved, she, and her lawyer, took him for all he was worth. At first, he went the extra mile, turned the other cheek, lost his shirt and gave up his coat too, and settled … for nothing. But then he hired Moses. And so he got even.

Yom Tov

Yom Kippur, which concludes the ימים נוראים, the Days of Awe, begins at sunset tonight.

In 2006 I went to my first (and only) Yom Kippur service. My friend Adam took three of us goyim with him to a local congregation’s service. That year he wrote a remarkable piece about it, which we refer to in my 2008 interview of him that, in a strange way, neatly incapsulates our friendship.

Adam has graciously allowed me to repost his Yom Kippur essay below. I’ll follow it up with a few notes of my own.

Yom Kippur as Manifest in

an Approaching Dorsal Fin

by Adam Byrn Tritt

It is Yom Kippur. A Monday. I have taken the day off work to walk, meditate, think. I have taken the day off work so I could go to temple the night before and not worry about the time, the hour, how late it was getting, when I would need to get up.

We asked our friends to go with us. In our back yard, playing with clay, our conversation set on cognates and religion. I mentioned the Buddha of compassion, Amitabha, and the other name for him, Amida. How the Amidah is the name of a prayer of compassion recited during the Yom Kippur service. How it relates to almonds, as the ancient Hebrews saw the almond as a symbol for watchfulness, promises, and redemption. How the part of the brain which we know to be the seat of our ability to see things in a global, compassionate way is called the amygdala, from the Greek amugdale, meaning almond. Craig started talking about the Kol Nidre prayer and, being Craig, translated it for us and we sat, transfixed, as often we do listening to Craig. Lee, Evanne, Beth and I, listening to Craig.

Of course we listen to Craig. He, translator of dead languages. He, who juggles biblical text back and forth from language to language, from meaning to meaning as though the passages are but palm-sized bean bags. He, of the three books of translations. Yes, we listen when he speaks.

As we talked, we discovered he had never been to temple, had never actually listened to the Kol Nidre. Neither had Beth nor Evanne and that, of course, was not a surprise, growing up in the Midwest: Ohio and Nebraska, Methodist. Right then, we asked if they’d like to go with us this Yom Kippur, to the Kol Nidre service—the only one we go to.

They were surprised. Craig said he was honoured. Evanne agreed with a clear look of shock on her face. Beth asked if we’re sure it was OK and told us how special it was to be asked, how appreciated it was.

That was months ago. We asked the small, local temple if we could come and bring three guests. No problem. May we have their names and do they have any departed they would like Yizkor candles for? Yes. We were set to go.

Erev Yom Kippur arrives. Lee is under the weather and cannot go. She asks that I go anyway and I resist but she does not want to disappoint our friends.

Evanne worries whether she should have her hair covered. Beth is concerned she looks like a “goy.” Lee tells her, jokingly, that she should proudly announce she is a shiksa. I suggest against it and let them know it is an honor that they are going and the congregation would be overjoyed they are there.

They are worried. No need to dress well; not for this congregation. But they do and Beth’s high heels put her so high above me she has to bend over and I must tip myself up on my toes to kiss her on the cheek.

Both wear black, notice their shoes are made of leather, point out they have worn black and now discover the color of the holy day is white. No one will be following all these rules. No one will notice.

Evanne, married, wears a scarf on her head, long and flowing, tied into her hair, nearly as long, nearly to her thighs. She could be Golda and Tevye’s shorter, forgotten daughter. She could be from the shtetle. No one will guess she isn’t Jewish. Beth actually looks Jewish and no one tells her this. How to explain what that looks like?

Craig fits in perfectly but is wearing shoes for the first time in, perhaps, more than a year. [Note from Craig: I live in Florida, and I am usually barefoot. When I must wear shoes, it’s sandals.] I offer him one of my tallit (prayer shawls) and a kipa I think will fit him well, gold and silver. He tells me he is honoured to be invited and I am privileged to give him my tallis to wear.

We arrive, are greeted, take prayerbooks and I search for a large print version, find one, enter, find a place in the pews close to the front. Myself, Evanne, Beth and Craig. I leave space to my right, where Lee would sit, where I would be able to see her.

We talk, discuss translation, Craig notices the Kol Nidre is not translated literally and, a game of telephone, shows me the text clues by showing Beth who shows Evanne who shows me, differences in font, serif versus sans serif, that tell a careful reader what is a translation and what is a paraphrase.

This congregation, Mateh Chaim, has, as yet, no home. And yet we have been welcomed even though we swell their ranks and available room. Even though there are non-Jews among us who need not be here. The congregation is growing and hopes to have one, but there is, in thoughtful congregations, a balance between the need for a building and the needs of community; the understanding an edifice takes money many of the people here tonight don’t have. It is the only congregation in Palm Bay. It meets tonight in a Methodist church. Behind the portable ark, containing the Torah, is a twenty-foot cross. It is not the building that makes a congregation.

I do not mind this so much. We talk, quietly, as we would before any service. Evanne tells us she is glad to see me misbehaving as usual as it puts her at ease.

“Misbehaving?” I ask. She answers that I have said “ass” twice since sitting down in the pews. She says it like this: “You said a-$-$ twice since sitting your a-$-$ down.” Silly. Anglo Saxon not allowed for a Methodist?

I think, momentarily, of our Yom Kippur in North Carolina. We were alone. No one around us had an understanding. I listened to Kol Nidre on Internet radio.

Joel Fleishman had a similar experience on the television program Northern Exposure in an episode called “Shofar, So Good” (1994) when, on Yom Kippur, he was visited by Rabbi Schulman. Our program opens with Joel, physician to Cicely, Alaska, carbo-loading in preparation for his day of fasting. He is attempting to explain Yom Kippur to the ever-interested residents as they eat at The Brick, the inn and tavern, and has little success. This is mostly because he has only a tenuous, superficial understanding himself. He knows the words, he knows the rules and proscriptions, takes care to keep the fast, not wash, not to care for personal convenience, to give the day up to feeling keenly, sharply one’s place in the world and relationship to God and our fellows. He sees the holiday as a noun with a set of rules, not a verb with a set of tools. To Joel, it is no longer a living tradition and he does not know what to do with it. On top of this, he is lonely for those who know his tradition.

Our Good Doctor Joel, while in the midst of his fast, was visited by the Good Rabbi Schulman who, as surprised as Joel, was lifted by a shaft of light and deposited in Cicely to help Joel understand what Yom Kippur is really about, and Dr. Fleishman begins the process of making amends. It is a journey, a Hebrew Dickensian vision quest, which starts with the Good Rabbi occupying the space of the top head of a totem pole. Jews, after all, are tribal too.

Not too surprisingly, the members of the town who understand Yom Kippur best are the shamans.

But tonight I am not alone and I revel in this. Craig tells us the history of the Kol Nidre. The actual translation, the “Kol Nidre Controversy” surrounding just what the proper place and ramification of the prayer is.

Kol Nidre means “All Vows” and it absolves us of vows and promises made that we needed to make to survive but knew were wrong. It apologises and gives release from the many times we said Yes when we wanted to say No, but did not because our jobs, food on the table, roofs over our heads, our safety, our security meant we had to say one thing, do one thing, when another was what we knew was proper.

He explains that my teaching middle school is my Kol Nidre. My giving grades, requiring students to do what they have no desire to, that is my Kol Nidre. When I teach them to pass a test when they want to learn creativity. That is my Kol Nidre. When I do that which I must to put bring food and security, when I do not call those around me on their actions because I must protect my job, that is my Kol Nidre. When I do not, can not, must not act in accordance with my true self; my Kol Nidre. When I do something I must instead of write and create. Kol Nidre.

Evanne points out that is exactly what the abbot at the Thai Buddhist temple told me, that I was doing what I needed to, and need only recognize that the needs of fitting into our community and of survival are taken into account in the realm of Karma.

Yet even those vows I take seriously. I uttered them. And so the Kol Nidre also protects us from ourselves; we make this prayer because we take vows so seriously we consider ourselves bound even if we make them under duress or in times of stress when we are not thinking straight.

The Rabbi, Fred Natkin, walks up to the bima (stage) and we look around. No fashion show here. Women in pants, men in dungarees, vests. Hats instead of kipas. I have done this as well as it is more comfortable, does not fall off, shades my eyes when reading. Many women have tallit and that is a sure sign of a rather liberal welcoming congregation.

The service starts and it is with great participation of the congregation, coming up to the bima, sitting down again after hugs and kisses. Always each moment, each prayer ends with hugs and kisses among all those on the bima. Evanne asks me if this is important. Among many liberal congregations, this is common, important, this contact and affection. I say it is a fitting way to end a prayer to love each other and who are we to argue, and I lean over and kiss Evanne on the cheek.

The congregation prays, meditates, responds, the rabbi sings, chants.

The time has come for the sermon. The rabbi speaks of science fiction. Reads a letter written by him to the neighbouring Moslem congregation offering aide and friendship after a shooting into the mosque this week. He is offering for the descendants of the two sons of Abraham, the children of Isaac and the children of Ishmael, to make peace and fight together for justice. This year the Jewish high holy days and Ramadan started on the same day. We have the same goals. The president of the congregation writes his thanks, appreciation and friendship in a letter to the newspaper, thanking the rabbi and congregation. He reminds us we must make the world the heaven we wish it to be. It is our job and what we are chosen to do. That we do not pray for peace, but pray to be peace. That Judaism is a religion of verbs. The prayers re-commence.

The Kol Nidre is sung. There are two tunes for this prayer. I was taught by a rabbi there is magic in the tunes themselves, in the music, so, if one does not know the words, hum, dai de dai, la la la, and that is good and will do the trick. But I want to sing and this is the other tune, the one Lee knows. It is the Sephardic tune, I believe, the one from the Mideast and not the Ashkenazic tune of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. I do my best. Craig knows the words but does not sing, unfamiliar with the tune even more than I. Evanne, somehow, reads more loudly than others, seems to fit, sounds clear, and I am frequently amazed by this.

More prayers, meditations, the Amidah and call for compassion. I feel this prayer as I did the Kol Nidre and look for my wife, see the empty space. I think of my own Yom Kippur Prayer. And when I have trouble following along with the official version, I recite mine to myself:

We open our mouths to proclaim how beautiful the world is, how sweet life is and how dear to us you are, Lady, Mother of All Living.

We stand here today to remind ourselves that we are all part of this web of creation. We are all linked, so that what any of us do affects all of us, and that we are all responsible for the Earth, and each other. We have chosen to be here today as a symbol of our commitment, our awareness of this connection.

Even so, we forget our promises and our duties.

We gossip, we mock, we jeer.

We quarrel, we are unkind, we lie.

We neglect, we abuse, we betray.

We are cruel, we hate, we destroy.

We are careless, we are violent, we steal.

We are jealous, we oppress, we are xenophobic.

We are racist, we are sexist, we are homophobic.

We waste, we pollute, we are selfish.

We disregard the sufferings of others, we allow others to suffer for our ignorance and our pride.

We hurt each other willingly and unwillingly.

We betray each other with violence and with stealth.

And most of all, we resist the impulse to do what we know is good, and we do not resist the impulse to do what we know is bad.

All this we acknowledge to be true, and we do not blame the mirror if the reflection displeases.

Lady, help us to forgive each other for all we have done and help us to do better in the coming year. Bring us into harmony with the Earth and all Her ways.

So mote it be!

In this prayer, we admit we are not perfect and proclaim we will make good on our mistakes even if we are not aware we have made them. We all make such mistakes. Such is the friction, the dukkuh as the Tibetans call it, of life. And we must have the compassion for others to apologise, to make amends, person to person. If we do not, we cannot go into the new year. If they do not accept, the guilt is on their heads if, and only truly if, we have honestly done our best to make amends.

We must also have compassion for ourselves and the ways we have transgressed against ourselves. Such is the message of the Amidah and Kol Nidre; we can start over and do better. Such is the message from Amida, Amitabha.

And we are cognizant we have made mistakes we are unaware of individually. For these, we say a prayer and ask forgiveness not of God, but of each other and offer our forgiveness as well.

More meditations, kisses, hugs. The Mourner’s Kaddish is said, and I quietly remind those with me this is what they gave those the names of the departed for. I think of those I have lost and feel keenly the empty space next to me, where my wife should be, and move slightly over more, closer to Evanne, leaving more room for my absent wife as though I was looking to be able to see her as I sang, but could not find her. I am missing her and think, sadly, at some point this space will be open, open and empty and not fillable. Thus says this prayer.

And with this, service ends. Craig mentions how so many of these prayers have been taken, nearly without change, for Christian services. Beth feels the continuity with the Methodist services she is familiar. We exit, putting our books back as we do, and head back to the house.

Lee greets us outside, still not feeling well but wanting to be social to a degree. I am grateful, and tell my friends so, that I was able to go to temple with those I love even when my own dear was at home. I was able to share this evening with them, this prayer, this holy day. I am grateful to them and happy.

They had said it was an honour to be asked. That night they repeated their gratitude and surprise. It is I who am grateful. It is I who am honoured. It is I who am, again, surprised, amazed and smiling. I hold them both and say thank you, then smile as they drive away.

* * * * * * *

Today I stay home for Yom Kippur. I do not go to temple, however. I plan to write, run, walk, meditate, remain quiet.

I get ready to go to the beach. On days like this I am reminded of some of the perks to living in Florida. It is October and I am going for a run on the beach. My ancestors would already be cold, wearing thick coats, and would have long collected the winter wood. I will be running by the waves wearing as little as I can get away with. I say to Lee, listening, that it is too hot to wear dungaree shorts, the only kind I have. I have two swimsuits, both old, hardly worn but seeming worn, nonetheless, the elastics having given up their ability to stretch, become brittle.

I have not purchased any in years and told myself I would not until my weight was down to where I wanted it. I might have to go back and revisit that idea. They were too small for years and I would not go to the beach. Now that they are too big and are unfit, do not fit, I put on the one with the best elastic. My wife shakes her head. No? Why not? Does it have a lining? No. She tells me I have lost weight and that will lead to needing a lining if I am planning on going running. She does not want me to be uncomfortable or, worse, injure myself, telling me the fat I use to have kept some things in place and, without that weight, I’ll want that lining as I go jangling up and down. I put on the other suit and it falls off. It has a cord, I pull it tight. It still hangs a bit and I’ll need a new suit soon.

I go off to Melbourne Beach and leave everything, including my sandals, in the car. Keys, wallet, glasses. I put about fifty cents in the meter and get one hour and fifteen minutes for my coins. I did not take sunscreen so I leave my shirt on, planning to take it off if I get too hot.

It is bright, clear, brilliant and the beach is quiet and nearly empty. I head to the shoreline and walk, briskly, south.

I practice an exercise as I go called the Walk for Atonement. At-one-ment, removing separation. Becoming one with what is around me, with the world and all that is in it. With time and space. If we felt at one with all things, who would we, who could we, hurt?

What is our place in this world? What is our place, in context to all that is? I walk. With my steps, I contemplate spans of time. A day. What does a day feel like? What does it feel like to exist a day? A year. How does a year feel? Ten years. Can I feel ten years? How plastic I am. How much one can change in ten years.

I do this every year. From then to one hundred. This year, I add fifty years. Fifty years. I am approaching that and can feel it. It is not far beyond my span now and I can understand that in a personal context. One hundred years. What does that feel like? I has and have relatives nearly that old. One thousand years. I can understand this historically but what does it feel like? I am uncertain. My place in it is, or can be, nearly a tenth. But how much a part do I actually play? My grasp on it is tenuous. Ten thousand years. Again, historically, I have an idea. Personally, it is too vast, too long. I have no context. What is my place in that span of time? Nearly none. One hundred thousand? None. None at all. A million?

As I reach a million, I see something I have never seen but which is astonishingly familiar in the water a scant twenty feet from me: a triangular dorsal fin, a triangular tail fin, both moving gracefully in the water so close if I wanted to, if I were fool enough, I could walk out to it and barely have my calves half covered by ocean. This is amazingly close for a shark.

I stand and watch. This is an interruption in the flow of the meditation. Or is it? A shark comes so close as I contemplate a million years that this seems like a message. It feels like a hello from distance of time and I can see, now, what that million years looks like. I cannot go to it so it, instead, has come to me. Today.

I am aware of a person next to me, fewer than a few feet away. “Is that what I think it is?”

What else could he be asking? It is safe, I imagine, to answer in the affirmative. “Yes.”

“I was going to go swimming.”

“Still going to?”

“I just moved here. This is my first time at the beach. Are they out there all the time?”

“Are you asking me if there are always sharks out there, or if death is always fewer than twenty feet away and swimming around us?”

He stares at me.

“The answer is yes to both. You’re just getting to see it today. Welcome to Florida. If you plan on hiking instead, remember, we’re the only state with all four kinds of venomous snakes.”

He walks off.

I continue my walk. With each step I think of a person I have wronged. I apologize. With the next step, I forgive myself as well. I do this until I can think of no more people, but I am human and I must have hurt more people than I think by simply the act of living. I apologize with each step, contemplating the many ways we hurt each other and never know it, cannot help it. And, when this is done, forgive myself.

As I continue to walk, I think of each person I know who has hurt me. I forgive them. It no longer matters. In the span of time, what could it matter? If they have not admitted guilt, what does it matter? I forgive them. I forgive them all. If I have thought badly of them for the wrong they have done, for this, even, I apologize and forgive myself.

Why carry guilt? Why carry anger? Why carry a careless word? Of what use is it in the span of years? A million years and how long am I here? There is a shark in the water.

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha. Gone, gone. Beyond gone. Past beyond gone. There is enlightenment.

I start to run. Barefoot I pad the sand beneath me. Step by step following the mean line of the surf. If the waves come in further, I lift my legs higher, pull up my knees, splash as each sole descends. This varies my running, changes the muscles used, increases my activity.

With each footfall, I think of a year of my life. A year. Each time I pad the sand beneath me: grains millions of years in creation, millions in erosion. Each step, a year. I run out of years quickly, in a matter of half a minute. I think of my potential lifespan and run them out in another half minute.

I think then of the people I love and run them out, each step a year of life. My family, less than a minute each, like the blink in time they are, we are. My friends, a minute. I think of those I know, enjoy the company of, gone in minutes and I do this consecutively but I know it is all concurrent, all gone, more or less, in the steps it takes me to run out mine. I think of those I don’t like. All gone too. No different. All the same. We are a set of footprints. We wash away.

I wish all people happiness and the root of happiness. I wish all people freedom from suffering and the root of suffering. Even those I don’t like. Especially. Now, before I become invisible among the sands. Now, before I wash away.

I have run out of people. I have not run out of beach. I continue, watching the evannebirds skitter the foamline as I splash and make impressions which are instantly gone behind me as the tide washes out. I run and am not tired. How much further?

I expected to run for a few minutes. I thought, how long can I run before I need to turn back? How far can I go before I know I am half-spent and turn around to run back or all spent and must walk my way back? But neither point comes. I run.

I run easily, no pain, barely sweating, my heart slow, my breathing calm. It was not long ago I would run five minutes and be exhausted. I would run and walk and run and walk in alternate minutes. Now I am easy and feel free and comfortable, open. How long have I been running?

I choose a point in the distance: a home among the many but different in colour than most, and decide to run to that, then turn around. On the return I can sense no reason to be heading back but my desire to return to my writing. Still, I am not tired, not worn, my breathing slow and full.

I see the salmon-hued building that signals where I started. There is the boardwalk, invisible behind the sea oats and dunes. I run up to the ramp and there I stop.

Once to my car, I look at the meter. I have been gone more than an hour and a quarter and it flashes at me. I have run for much of that time. I have run for nearly an hour. It is not a marathon, but it is an amazement, an accomplishment, and I have a sudden keen sense I have not eaten anything today but half a cup of milk. I am not fasting. I cannot fast. It is bad for my health and is, therefore, forbidden by Talmudic law. Certain people and people under certain conditions, according to the Talmud, may not fast. I have brought nothing by way of food with me and across the empty street is a Coldstone Creamery.

I get my things from the car, brush off my feet, put my sandals on, put another quarter into the meter and walk over. What could make this day more perfect than adding an ice cream?

There is a Starbucks on one side of it and a Bizarro’s Pizza on the other. There use to be café here Lee and I ate at once; had lunch with Jeannie, Joseph, and Connor on our first visit to Melbourne. It left with Frances or Wilma or one of the September storms to visit in 2004. The building is still empty, partial.

I walk into Coldstone. It is slightly after twelve and it feels as though there have been few customers today. I ask the young lady behind the counter for plain ice cream with no fat and no sugar. They have ice cream with no flavouring; simply the taste of milk, crystalized, thick and solid. No sweetener. Why would milk need sugar? She is happy to oblige and what size? One cup. A small.

Would you like anything in that? No. Wait, yes.

Please, if you would, some almonds.

Michael Weiss has written an excellent article in Slate discussing the “Kol Nidre Controversy.” I wrote a piece about it too, but it seems to have been lost in the mists of time, or perhaps in a hard drive crash.

For me, it’s not atonement or absolution that gives one a new start, but this abjuration of everything to which one has committed oneself out of necessity or by mistake—this stripping off of falsehoods and limitations in favor of truer garments—that empowers one to move forward. Yom Kippur reminds me to decide, tonight and tomorrow and every new day, who I am and what my greater truth is. To declare it and allow it to make me stronger and freer.

I think of the empty space next to Adam at the service that night, where Lee should have been, and the empty space she has left in our lives now that she’s gone. Though of course she isn’t gone. She fills the space we leave for her, and we are enriched.

Gut yontiff, friends.

The Quest of the Historical Pythias

This blogpost will make its quest of the historical Pythias a bit crookedly. I’m excited about a new book, so more on that below.

I think it’s easier to start elsewhere, in more familiar territory for most. When it’s “the quest of the historical Jesus,” then we all know which particular Jesus is meant by that. Never mind that his name was probably pronounced as יְהוֹשֻׁעַ Yĕhôshúa’ and, as such, could easily have been confused dozens of others whose namesake is the post-Pentateuch Ἰησοῦς of the “Book of Joshua.” Yes, even this character may be more fiction than fact, if the source is simply, what William H. Propp, Baruch H. Halpern, and David Noel Freedman conclude is “the book of Joshua,” or “a literary creation, a historico-theological fiction, whose primary sources were the already exiting literature of Israel.” So we look back. There are allusions and perhaps disambiguated confusions before Joshua and the book of Joshua. These are in Torah, very specifically with reference to this name, in bəmidbar Sinai. For example, in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, particularly in Numbers 13:16, we read of this historical moment: “And Moses called Hoshea the son of Nun Joshua.” Well, I’m now quoting from the 4 century old King James Version, which renders Matthew 1:21 as follows: “And she shall bring forth a son, and you shall call his name JESUS: for he shall save his people from their sins.” One story draws from another, one history from another, one fact or fiction from another. The remarkable thing about the quest of the historical Jesus is that we all understand who the quest is about. We don’t really have to start with fact or with fiction just so long as we all agree on which Jesus is, or is not, the historical one. So let’s say there was a real Jesus in history. Yes, that one. What, then, do you or I require of him?

As I start this post, I’m trying to get at the fact that good “historical” literature is not only burdened by “faith.”

It is so very much the case, nonetheless, that religious literature — that the Gospels of Jesus, the various ones of them — do make the case for faith. Our BLT co-blogger Theophrastus reminds us of this in a recent comment after an earlier post: given the faith burdens put on religious historical literature by Protestant readings of the gospels in particular, “it must be a fact that Moses received the Torah at Sinai, Jesus physically ascended into heaven, Mohammad visited Jerusalem, Moroni gave Joseph Smith the plates, Buddha was enlightened under the tree (perhaps the same tree from which the apple zonked Isaac Newton), Krishna advised Arjuna, etc.” I’m tempted to suggest that “faith” in the Protestant hermeneutic is somewhat literary or, vice versa, that what’s literary sometimes really looks like Martin Luther’s Glauben.

Moving along in this post, I’m trying to get at the fact that good “historical” literature is not only burdened by “faith.” History writing and history reading is burdened with going beyond the facts if it’s to be real history. History making and the reception of history really is about good story telling too. There’s an a-religious belief in it, or else it’s not, well, believable.

Aristotle, even the historical one who wrote The Poetics supposedly, said something like “It was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic, yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.” Yes, I get the fact that, in English, originally, this was the historical Samuel Taylor Coleridge saying these words that sound so much like our Aristotle. All this reminds me how Catherine Elgin (in her book, Between the Absolute and the Arbitrary) talks about what has happened, through history, when we try to speak of our historical figures; she writes about us as we talk (or write) about Aristotle:

Aristotle, of course, was not named “Aristotle”; the name he went by had a different pronunciation and a different spelling. So the claim that our use continues the chain that began with his being baptized “Aristotle” needs refinement. Then there is the worry that chains that originate in a single stipulation may later diverge. In that case a term has two different reference classes despite its link to a single introducing event…. Ambiguity occurs because correction… allows for alternative continuations of the causal chain…. Each continues the chain, but the two uses of the word… are not coextensive. Nor do we always succeed in referring to what our predecessors did, even when we intend to do so.

Well, then. Let’s just back up. We must agree that “fake” history can be written. We want to agree that that’s “not history”; it’s not real history anyway. Let’s also agree that when Jesus tells a fable, aka a parable, in one of the Greek gospels, it might not co-incide with facts of history. None of us wants to be duped. Nobody reading true truth or real reality or historical history wants to make it only believable as a matter of religious faith. And yet readers of the Greek gospels can and do get into discussions of whether a certain Lazarus in the bosom of a certain Abraham or a certain Jonah or a certain Adam were historical for the Jesus about whom the Greek gospel writers wrote. What does it matter?

So what I’m trying to come to is our agreement that good history written (or told) works like fiction in most cases. None of us really asks for “just the facts.” Philip Yancey, writing his history of Jesus (aka The Jesus I Never Knew) gets at some of this reading another historian:

Pulitzer Prize winning historian Barbara Tuchman insists on one rule in writing history: no “flash-forwards.” When she was writing about the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, for example, she resisted the temptation to include “Of course we all know how this turned out” asides. In point of fact, the Allied troops involved in the Battle of the Bulge did NOT know how the battle would turn out. From the look of things, they could well be driven right back to the beaches of Normandy where they had come from. A historian who wants to retain any semblance of tension and drama in events as they unfold dare not flash-forward to another, all-seeing point of view. Do so, and all tension melts away. Rather, a good historian re-creates for the reader the conditions of the history being described, conveying a sense that “you were there.”

Anyone who has seen the film Titanic twice may still get that twinge of hope, while watching the second time, that maybe not all will be lost in the end. There’s something in the literary, in the literature of history, in what some like to call historiography, that goes beyond facts. That something never necessarily goes against the facts. But the story telling of the history is most believable when it’s not just a timeline of verified “fact checked” facts.

Historian and feminist and rhetorician Cheryl Glenn knows that even the factual writing of good history requires more than just the facts. (Again, we’re not talking about blind religious faith or any sort of gullibility). Glenn looks at how men through the ages, since Socrates, have been willing to fill in around the facts, to rely on stories, say, written by Plato and by Xenophon and by Aristotle as if factual. The best histories of Socrates do not reduce to facts. Nobody writing about Socrates since Plato, Xenophon, and Aristotle has just offered only the facts. (Again, we’re not talking about merely religious fancy either). Glenn gives her defense then for writing a history of Aspasia, based on stories by Plato for example. Men write histories about Socrates, and so her history of Aspasia, I will claim here, is as good as any written. Glenn’s method? Just as good as anybody’s:

We must risk, then, getting the story crooked. We must look crookedly, a bit out of focus, into the various strands of meaning in a text in such a way as to make the categories, trends, and reliable identities of history a little less inevitable, less familiar. In short, we need to see what is familiar in a different way, in many different ways, as well as to see beyond the familiar to the unfamiliar, to the unseen.

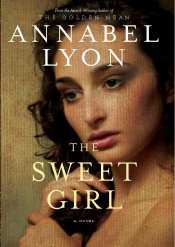

I’m taking an awfully long time to say something I really want to stress. There’s an exciting new book out about a woman, a woman of history. It’s written by a woman who seems to put a lot of herself in the history. The historian and the subject of her history even look the same. Here’s the author of the history (a photo) and her book cover (an artist’s painting of the one about whom the history is written). Notice the resemblances:

I really don’t know if that’s to make the one more realistic, more believable, or not. What I’ve been reading is that the author has had to go on a lot of imagination in her quest of the historical Pythias.

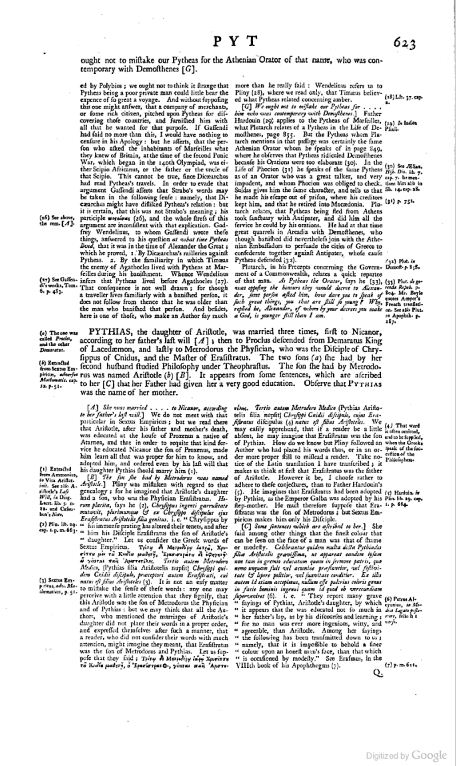

When we say the quest for the historical Jesus, then we all know which Jesus we’re talking about. But when we say Pythias, we don’t have much to go on. Which one? The wikipediaists still haven’t added this one whom this new history has been written about: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pythias_disambiguation. Here’s a half page from an old encyclopedia:

Here’s a bit of a close up view (updated spellings and some footnotes elided); this is from that old encyclopedia that men in history (namely Pierre Bayle, John Peter Bernard, John Lockman, Thomas Birch, George Sale) wrote —

PYTHIAS, the daughter of Aristotle, was married three times, first to Nicanor, according to her father’s last will;then to Proclus descended from Demaratus King of Lacedæmon, and lastly to Metrodorus the Physician, who was the Disciple of Chrysippus of Cnidus, and the Master of Erasistratus. The two sons she had by her second husband studied Philosophy under Theophrastus. The son she had by Metrodopiricus, was named Aristotle.It appears from some sentences, which are ascribed to her [C] that her Father had given her a very good education. Observe that Pythias was the name of her mother.

[C] Some sentences which are ascribed to her] She said among other things that the finest colour that can be seen on the face of a man was that of shame or modesty…i. e. “They report many grave sayings of Pythias, Aristotle’s daughter, by which it appears that she was educated not so much in her father’s lap, as by his discourses and learning; for no man was ever more ingenious, witty, and agreeable, than Aristotle. Among her sayings the following has been transmitted down to us; namely, that it is impossible to behold a finer colour upon an honest man’s face, than that which is occasioned by modesty.” See Erasmus, in the VIIIth book of his Apophthegms.

Notice how this Pythias, this historical one, is written in relation to men. Even the words we have of her in our histories are “by his discourses and learning,” that is by her father’s discourses and learning, by Aristotle’s discourses and learnings (according to Erasmus). Notice how I’ve ranted about this before. I’ve insisted that we can’t really do the quest of the historical Aristotle without really doing the quest of the historical Pythias:

But what do we know of Phaestis (Aristotle’s mother), Erpyllida (the foster mother), Arimneste (the older sister), Pythias (the first wife who bore their daughter), Pythias (the daughter), Herpyllis (the second wife who bore their son Nichomachus, the namesake of Aristotle’s father)? Who are Aristotle’s grandmothers, and what do we know of them, and what did he know because of them? Does anyone still hear the voices of these women who Aristotle, likely, could not help but hear?

And I’ve ranted about this before:

And he names his most famous treatise on ethics after his father and his son, both named Nikomachus; but he never does anything like that for his mother Phaestis or his concubine (second wife) Herpyllis who bore him his son or his wife Pythias who bore him only a daughter, whom he named Pythias after her mother. Then, again, he studied males and females very carefully and concluded by his logic that females are defective males.

Aristotle might laugh at the book I’m about to tell you more about. We imagine, he might laugh, this historical factual Aristotle.

But the historian is an archaeologist, a forensic scientist, a forensic anthropologist. Today, according to one reviewer, this historian actually learned from the methods of a forensic anthropologist:

To conduct such research, [this historian] journeyed to Greece in May 2010 with a group from Carleton University’s department of classics.

“I’m so glad that I did because there’s so much that ended up in the novel that wouldn’t have occurred to me otherwise,” she said.

Those elements include the types of food the characters eat in the story, the tools they use, and their ancient practices, one of which is burying dead babies with puppies.

[The historian] learned of that practice from a forensic anthropologist.

“She’s like ‘CSI: Ancient Greece’ woman,” [the historian] said with a laugh. “She would examine bone remains and figure out how people had died. … Some of the work that she had done and written about was excavating these old dry wells from ancient times and they were full to the brim of these bones of babies and of puppies.”

Experts concluded some of the babies were born with physical deformities and were likely victims of mercy killings by midwives who buried them with puppies so they had companions as they moved on into the next world.

[The historian] also learned about the magic women practised in those days to try to control their fertility and love lives, among other things.

“When we think of ancient Greece, we think of centaurs and Zeus throwing thunderbolts and stuff, but we don’t think of these women trying to take some kind of control of their lives,” said [the historian] .

Well, the book is fiction. It’s a history. It’s about as much as we know factually of the historical Pythias, in our quest. It’s by Annabel Lyon, blogger, novelist. It’s getting some good reviews. I’ve already ordered my copy and have read the book’s opener available online free. I hope this opens up more conversations about our quests, our histories, our stories, and our suspensions of our disbeliefs. I hope we learn more about Pythias, just as we can easily learn more about Joshua and Aristotle and Jesus.

Jesus speaks of his wife: Now That She’s a Fake

Now that fellow bloggers are asking – and answering – “Is the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife a Fake?“. . . ,

Now that somebody is finally calling into question “the Academy’s and Church’s continued exclusion of single persons” – and blogging at least – “Two of the best responses” to the brouhaha . . . ,

It’s time for the perfect elegy. Jesus said to them (that is, to his disciples), “My wife” . . . ,

And, then, since they were arguing so typically about so many other things (these men), he turned and said to her (or perhaps still to them):

NATURE’S lay idiot, I taught thee to love,

And in that sophistry, O ! thou dost prove

Too subtle ; fool, thou didst not understand

The mystic language of the eye nor hand ;

Nor couldst thou judge the difference of the air

Of sighs, and say, “This lies, this sounds despair” ;

Nor by th’ eye’s water cast a malady

Desperately hot, or changing feverously.

I had not taught thee then the alphabet

Of flowers, how they, devisefully being set

And bound up, might with speechless secrecy

Deliver errands mutely, and mutually.

Remember since all thy words used to be

To every suitor, “Ay, if my friends agree ;”

Since household charms, thy husband’s name to teach,

Were all the love-tricks that thy wit could reach ;

And since an hour’s discourse could scarce have made

One answer in thee, and that ill array’d

In broken proverbs, and torn sentences.

Thou art not by so many duties his—

That from th’ world’s common having sever’d thee,

Inlaid thee, neither to be seen, nor see—

As mine ; who have with amorous delicacies

Refined thee into a blissful paradise.

Thy graces and good works my creatures be ;

I planted knowledge and life’s tree in thee ;

Which O ! shall strangers taste? Must I, alas !

Frame and enamel plate, and drink in glass?

Chafe wax for other’s seals? break a colt’s force,

And leave him then, being made a ready horse?

Oh. Right. That wasn’t Jesus complaining about his wife, his lover, (that woman) in Elegy VII. It was John Donne (whole poem, fragmented poet, “fake” exposer).

May the hair on your toes never fall out

I think it may be a promotion by the publishers; but still I want to give a hearty greeting to everyone celebrating Hobbit Second Breakfast today (in celebration of the 75th anniversary of the book). My mother first read the Hobbit to me when I was just a little tyke, and I remember liking it a lot; and I still like it today.

There are zillions of editions to choose among, but my preference is for editions with Tolkien’s illustrations. I can recommend the green leatherette slipcased edition, which is elegant, but not pretentious, and printed in a way that either an adult or older child could enjoy. Also worth noting is the annotated edition (I learned from it); the boxed set with The History of the Hobbit and the new book The Art of the Hobbit (US edition, British edition – the British edition is slipcased and better]).

Thomas Shippey has an insightful article today in the Telegraph:

What has made the book such an enduring success? There are lots of reasons why one would not have expected it to be. Too much poetry! No female characters at all! (How will Jackson get round that one?) A lot of professorial quibbling over words!

But maybe Tolkien’s boldest defiance of accepted children’s-fiction practice was that he offered no child figure for the reader to fix on. It’s true, the hero Bilbo Baggins is “only a little hobbit”, so he’s a kind of surrogate child, but he’s put in positions no child could be expected to identify with.

Like finding himself alone, in the dark, playing riddles for his life with a creature who means to eat him, or being trussed up by a giant poisonous spider, or — worst of all, alone and in the dark once again — being sent down a tunnel at the end of which he can hear a dragon snoring. Tolkien presents a very cold-blooded image of courage, and expects it to be understood.

He adds to it the element we call moral courage. Bilbo decides (on his own again) that his dwarf companions have got it wrong in their greedy defence of the dragon treasure, and so secretly gives away the greatest treasure of all, the Arkenstone, to his friends’ besiegers, to use as a bargaining point. And then he goes back to be exposed, in the end to confess, because they’re his friends still.

Anyone could have told Tolkien this is not kids’ stuff. Nor, for instance, is the death of Thorin Oakenshield. An American lady told me once that she read the whole book to her sons, aged seven and ten, and when they got to this scene, she saw the tears rolling down their cheeks.

Not very politically correct stuff, but interesting literature need not be politically correct at all. I would certainly be distressed if all children’s literature lacked female characters, but for a tale told in “Icelandic style” it hardly seems a strike against the book. (One can make similar remarks against many children’s books – except for a brief appearance by Mrs. Hawkins, there are no female characters in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, for example.)

There is another brief opinion piece by Corey “The Tolkien Professor” Olsen in the Wall Street Journal. Olsen has some great podcasts, and I bet his book [which I have not yet read] is much better this excerpt (apparently placed by the publishers.)

I should mention briefly the forthcoming PeterJackson films (apparently, this short film is becoming a film trilogy). I cannot fathom how the movie can possibly compare favorably with the book. (The Lord of the Rings movies were exquisite from a technical point of view, but I think that most people who knew the books well found them disappointing, since they did not convey the many genres and “complete description of a world” effect that Tolkien’s adult sequel to the Hobbit had.)

Kinship terms in Hebrew

Dana asks,

Is adelphoi used at all in C1 literature to indicate sibling-by-blended-family or cousin?

To answer that, one needs to start with Hebrew kinship terms, at least I do. It’s as close as I can get to Aramaic, the language spoken by those who feature in early Christian literature. The first thing to realize is that no Bible translation (that I am familiar with) even begins to provide insight into Hebrew kinship terms. Some pretend to.

The Hebrew word אח means “brother, sibling, fellow.” It can refer to a boy who has the same parent as you do, any sibling, or someone, male or female, who belongs to the same group or nation. “Fellow Hebrew” or “Fellow Christians” are perfectly acceptable ways to translate this word. It communicates the meaning much better than the word “brothers” which sounds in English like a male cabal, bent on no good!

But how then does the Hebrew language refer to one’s cousin? A quick search of various Bible translations may suggest that there is a Hebrew word for cousin, but that is a trap. Here is an example. I have chosen the ESV, as the English translation, since it claims to be literal.

or his uncle or his cousin may redeem him, or a close relative from his clan may redeem him. Or if he grows rich he may redeem himself

אוֹ-דֹדוֹ אוֹ בֶן-דֹּדוֹ, יִגְאָלֶנּוּ, אוֹ-מִשְּׁאֵר בְּשָׂרוֹ מִמִּשְׁפַּחְתּוֹ, יִגְאָלֶנּוּ; אוֹ-הִשִּׂיגָה יָדוֹ, וְנִגְאָל

Now this verse clearly refers in Hebrew to the uncle, specifically one’s father’s brother, and the son of one’s father’s brother. This expression, בֶן-דֹּדוֹ , is not a word for cousin. It does not refer to the son of one’s mother’s brother or sister, or to a daughter or any other sort of cousin. It is specific to the Hebrew kinship system. In Jeremiah 32, the same Hebrew term is used.It is specifically the son of one’s father’s brother.

So the ESV is just pretending that there is a Hebrew word for cousin. There isn’t one that is used in Biblical Hebrew. I suggest that this is not a passage about male authority but about prior responsibility in this kinship system. Anyone can redeem the poor person, any relative at all, so of course a wealthy woman could do so. But the father’s brother, or his son in his stead, has a prior responsibility in this cultural context. This responsibility does not confer any authority. The idea is to rescue a poor relative and set them free.

Curiously, in this passage in Leviticus 25, the ESV translates the plural of אח as “brothers” when it is clear that either a woman or a man could be the “poor relative” that is referred to here. So the real meaning is lost. But then the phrase בֶן-דֹּדוֹ , which means the “son of the brother of one’s father,” is translated as “cousin.” Once again meaning is lost. So frustrating!!

Here is the passage in the ESV,

47 If a stranger or sojourner with you becomes rich, and your brother beside him becomes poor and sells himself to the stranger or sojourner with you or to a member of the stranger’s clan, 48 then after he is sold he may be redeemed. One of his brothers may redeem him, 49 or his uncle or his cousin may redeem him, or a close relative from his clan may redeem him. Or if he grows rich he may redeem himself.

And here it is in The Contemporary Torah,

If a resident alien among you has prospered, and your kin, being in straits, comes under that one’s authority and is given over to the resident alien among you, or to an offshoot of an alien’s family, [your kin] shall have the right of redemption even after having been given over. [Typically] a brother shall do the redeeming or an uncle or an uncle’s son shall do the reeeming – anyone in the family who is of the same flesh shall do the redeeming; or, having prospered, [your formerly impoverished kin] may do the redeeming.

The Contemporary Torah translates the word אח as “kin” since it clearly refers to any relative, not just a male sibling. And it correctly translates בֶן-דֹּדוֹ as “uncle’s son” to emphasize who typically has the first responsibility. But no family member is restricted from redeeming a relative. This is not a restriction to only “the uncle’s son” but an indication of what was normal practice in that kinship system.

So, the upshot is that there is no generic Hebrew word for “cousin.” Could the word אח then mean “cousin?” My guess is that the Hebrew would typically say “the children of my mother’s brother” or some such expression, but I am not sure.

In Greek there is a word for cousin, and here it is in Col. 4:10 – καὶ Μᾶρκος ὁ ἀνεψιὸς Βαρναβᾶ. I have not answered Dana’s question. I don’t know the answer for sure. I am still thinking about it. I really do think that Jesus had actual brothers and sisters. Why not?

And yes, I highly recommend The Contemporary Torah as a way to gain insight into the original Hebrew.

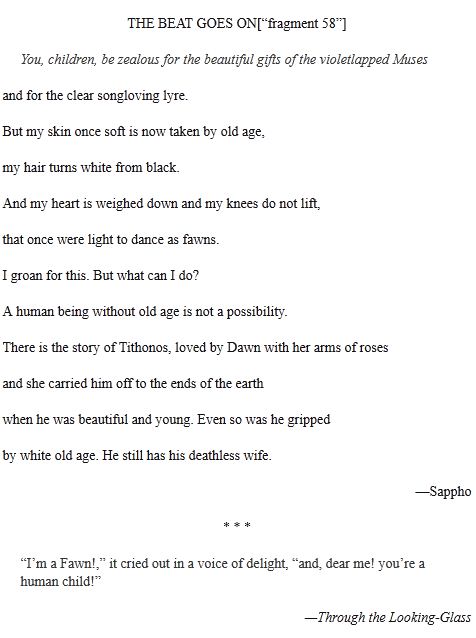

The Gospel of Tithonos’ Wife: The No News of a New Fragment of Text

What good news does a new fragment of text bring? Did Jesus Christ have a wife? Doesn’t this constitute a new gospel? These are questions many many are asking and answering now that Karen L. King of Harvard Divinity School has shared publicly a new fragment of text that somebody anonymously shared with her.

What I’d like to ask is why the news of Tihonos’ Wife wasn’t as big as this Jesus’ Wife news. Why wasn’t that news at least a little bigger? Is “no news” really “good news” and “new news” really gospel? Why if it hints of “biblical” a “whole fragment” gets so much more attention than if it hints of “classical”? Or, why the hype now? Why not then?

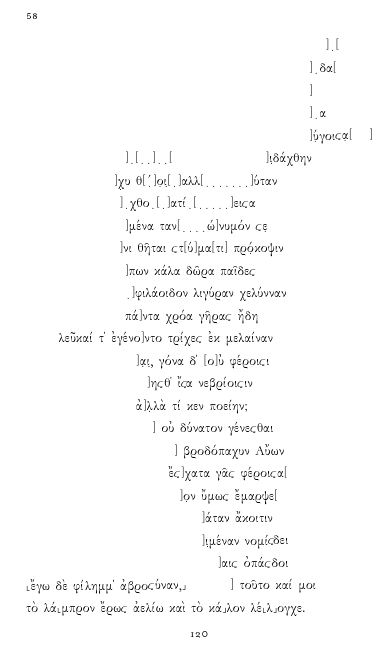

You know who I’m talking about, right? You know I’m talking about the public sharing of that “new text” of fragment 58 of a poem by Sappho. Yes, that’s right. It made that big splash on the 24th of June 2005, when Martin West announced in The Times Literary Supplement the following:

[T]he identification of a papyrus in the University of Cologne as part of a roll containing poems of Sappho. This text, recovered from Egyptian mummy cartonnage, is the earliest manuscript of her work so far known. It was copied early in the third century BC, not much more than 300 years after she wrote.

The TLS even reproduced an image of the new fragment, which looks just like this:

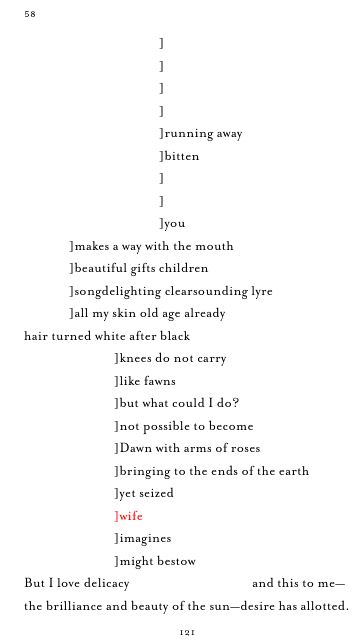

Many got to work, even at Harvard, and reconstructed the lines of the poetry of Sappho, so that it is more readable, like this:

So what was new? And so what? What questions remained? And what was really new? And why not more hype, since this confirmed a man had his wife?

Well, Fragment 58 that contained the lines of poetry by Sappho had once looked more like this:

And this provided much cause for speculation. Was Sappho a lesbian? Why did Plato call her the tenth muse? And who had the wife?

Well, translator Anne Carson, the best translator Sappho’s ever had, said things like this (in her fragmented translation, whose book cover is that image immediately above here):

Sappho’s fragments are of two kinds: those preserved on papyrus and those derived from citation in ancient authors. When translating texts read from papyri, I have used a single square bracket to give an impression of missing matter, so that ] or [ indicates destroyed papyrus or the presence of letters not quite legible somewhere in the line. It is not the case that every gap or illegibility is specifically indicated: this would render the page a blizzard of marks and inhibit reading. Brackets are an aesthetic gesture toward the papyrological event rather than an accurate record of it. I have not used brackets in translating passages, phrases or words whose existence depends on citation by ancient authors, since these are intentionally incomplete. I emphasize the distinction between brackets and no brackets because it will affect your reading experience, if you’ll allow it. Brackets are exciting. Even though you are approaching Sappho in translation, that is no reason you should miss the drama of trying to read a papyrus torn in half or riddled with holes or smaller than a postage stamp — brackets imply a free space of imaginal adventure.

Here are the pages, then, of Fragment 58 by Sappho and then of its translation by Carson:

And beyond the brackets, far from the implications of that free space of adventure so imaginal, Carson refused to venture. She, in fact, talked of others who would conjecture, who would make Gospels out of nothing, nothing but fragments. And so she added this word of observation, of caution:

A duller load of silence surrounds the bits of Sappho cited by ancient scholasticists, grammarians, metricians, etc., who want a dab of poetry to decorate some proposition of their own and so adduce exempla without context. For instance, …. [s]ome shrewd thinking of Sappho’s about death is paraphrased by Aristotle:

Sappho says that to die is evil: so the gods judge. For they do not die.

–Aristotle Rhetoric 1398b = Sappho fr. 201 VoightAs acts of deterrence these stories carry their own kind of thrill — at the inside edge where her words go missing, a sort of antipoem that condenses everything you ever wanted her to write — but they cannot be called texts of Sappho’s and so they are not included in this translation.

And then the new text was discovered. Carson was right to be patient for it, not to overstep. And she, then, at that time, at that very right moment, rightly made her confession. She wrote:

I confess I used to like fragment 58 in its incorrect form. It had fawns wandering through the middle and an uncontainable ending so packed with abstract words it read like Wittgenstein on one of his hooligan days. I made a little book about it once years ago, with paintings of fawns and much analysis of the ending, now obsolete. Funny how time carries things out of sight.

And she explained, then:

The text printed in the TLS by Martin West is not exactly a “new Sappho” but a more nearly complete and more correct version of a text that had been numbered fragment 58 in most editions. By collating the old and new versions of this fragment, scholars are able to say for sure where the poem begins and ends, what almost all the words are, how to understand its metrical form, and how to read its mythical exemplum. Now the fawns are relegated to a simile and the flash ending belongs to a different poem. It is a quieter composition. But poetically indisputable in the way that Sappho’s poems are.

And then she offered her translation of the newly discovered text, entitling it as a continuation of the old:

What Carson, the Greek reader of Sappho and her English translator, maintained was this:

“Sappho is not trying to startle her audience with inventions semantic or figural. Her material is facts (Tithonos is a mythic fact), not metaphor, not décor, not afterthought.”

To me, this is one of the most important lessons of this new old text. That is, Carson let Sappho’s text be Sappho’s text and not more. When more information finally came out about the original text, likely, then the translator still did not invent more than the poet does. And, even though Carson conjectured early on that “scholars are able to say for sure where the poem begins and ends,” the fact is that scholars continue to debate this very point. The fragments, old and new, do not settle all.

William Harris, on this very text, on the new understandings of the poem, can only conclude this:

You have a readable poem here as it stands, but questions and arguments in the halls of Academe will go on for a long time. First there are problems about reconstruction of the text where lines are damaged. Then they may be sub-meanings of what Sappho was trying to say whether in a socially conscious framework, or a Lesbian mode or from a Feminist point of view. But for the literate reader of poetry, the poem is sufficient to stand on its own metrical Feet. It has come through the decay and attrition of a hundred decades and that, beside the wording of this lovely and triste poem itself, is miracle enough.

I wonder if biblical scholars and bible bloggers and bible hobbyists and religious Bible types will recall that story of Tithonos, the material of facts of the myth. There may be more truth therein than in whether Jesus Christ, the historical, had a wife from what appears partially penned by someone once upon a time.

The Clements and the literal Phoenix(es)

Yesterday, while many of us were mused by the wife of Jesus, our BLT co-blogger Victoria was elsewhere (at her own blog) giving us her Impressions of First Clement. She makes this wonderful comment:

The most unusual argument here was his appeal to the phoenix as an argument for the resurrection of Christ: he does not seem to discuss it as a legend, but as natural history about this remarkable creature that lived in Arabia. One wonders whether this was one of the reasons this letter didn’t make it into the canon — Richardson notes that other writers of the time were not so credulous of the story of the phoenix. I’m not sure if I wish it had; I can’t help but wonder how that would have shaped the debates over biblical literalism!!

Some years ago, one Taylor Marshall posited where Clement of Rome must have found this whole notion:

Was Clement nuts or was he speaking from a valid tradition?

As it turns out, the tale of the phoenix is actually found in the Bible’s oldest book – the book of Job. Job 29:18 reads,

Then I said: ‘I shall die with my nest, and I shall multiply my days as the phoenix.’

Clement’s idea that the phoenix dies and its nest and the returns for a length of days has its origin here.

The Hebrew translation is debated. The Hebrew word chol is typically translated in one of three different ways:

1. sand

2. phoenix, as in the mythical bird

3. palm tree

Well, now we have to take this mythical bird literally. Or so it would seem. We may just want to fast forward from Rome, from the Clement there, to Alexandria, to the Clement of Alexandria. In the later Clement’s Protrepticus, or Exhortation to Heathen, or literally his προτρεπτικὸς πρὸς Ἕλληνας, or his chiding of the Hellenes, that is, the Greeks, there are these two phrases:

1. τὴν κεφαλὴν τοῦ νεκροῦ φοινικίδι

2. τῶν τὴν Φοινίκην Σύρων κατοικούντων

And if we fast forward from the Hebrew Job to Herodotus’s histories (before we get to the Greek Job invented in Alexandria), then we find not only the Greek historian’s literal allusion to this mythical bird, but we also find a second thing, the river Phoenix:

1. τῷ οὔνομα φοῖνιξ

2. ἔστι δὲ ἄλλος Φοῖνιξ ποταμὸς

Well, this is all Greek to me. Let’s get it into some English.

Clement of Alexandria wants his readers to know these two things at least:

1. If you wish to inspect the orgies of the Corybantes, then know that, having killed their third brother, they covered the head of the dead body with a purple cloth, crowned it, and carrying it on the point of a spear, buried it under the roots of Olympus.

2. Nor shall I forget the Samians: the Samians, as Euphorion says, reverence the sheep. Nor shall I forget the Syrians, who inhabit Phœnicia, of whom some revere doves, and others fishes, with as excessive veneration as the Eleans do Zeus.

And Herodotus has written to his readers about two things at least:

1. the bird called Phoenix

2. the river by the same name

And all through the Alexandrian Septuagint we find such references, even in the Pentateuch proper. And into the New Testament (even Luke’s book of Acts) there are Phoenix places (such as that port of Crete, which is still to this very day so named as it was in Acts 27:12).

So part of the confusions is attributable to the ambiguities — in Greek — in this word. It’s used by Hesiod and by Homer and by Herodotus and by Isocrates and by Plato’s Socrates and by Plato’s student Aristotle and by oh so many Greek playwrights such as Euripides and Aristophanes. It seems to mean purply-red or reddish purple and appears to have been often associated with peoples living by water, and then of course, with this bird. Of course, in translation into English and such, there are these confusions. Here’s the Liddell and Scott entry on the bird word:

φοῖνιξ 1

I. appellat. a purple-red, purple or crimson, because the discovery and earliest use of this colour was ascribed to the Phoenicians, Hom.2. as adj., ὁ, (also φοίνισσα as fem. in Pind.), red, dark red, of a bay horse, Il.; of red cattle, Pind.; of fire, id=Pind., Eur.:— φοῖνιξ and its derivs. included all dark reds, from crimson to purple, while the brighter shades were denoted by πορφύρεος, ἁλουργής, κόκκινος.II. the date-palm, palm, Od., Eur., etc.III. the fabulous bird phoenix, which came from Arabia to Egypt every 500 years, Hdt.:—proverb., φοίνικος ἔτη βιοῦν Luc.

The Gospels of Jesus’ Wife // and of Jesus’ literal Mother and Jesus’ literal Brothers // !!!

Today, many are reporting Karen L. King’s report of what she’s calling the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.”

Here, hear King telling us for yourself (and listen to her on this video starting around second 20 all the way to 30). Listen to what she says,

The most exciting line in the whole fragment, however, is the sentence “Jesus said to them (to his disciples that is), Jesus said to them, ‘My wife’//…”

Now, look for yourself at King’s own website:

The most exciting line in the whole fragment, however, is the sentence ‘Jesus said to them (to his disciples that is), Jesus said to them, “My wife’//…”‘ — Karen L. King

——–

This news of the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” based on the fragment is just as exciting as the news of that “Gospel of Jesus’ Mother and Brothers” based on other fragments of text. Specifically, we might recall the “whole fragment” from the 1894 Scrivener New Testament (TR1894), more specifically Minuscule 705:

Here’s that transcription:

ειπεν προς αυτους μητηρ μου και αδελφοι μου// !!!

Here’s the translation:

(Jesus) said to them (to his disciples that is, Jesus) said to them, “My Mother and My Brothers…”// !!!

And to view the video, Please View

View Minuscule 705 and over 3,000,000 other topics on Qwiki.

What this surely implies, however, is that Jesus was actually talking about his mother literally and actually also about his brothers literally. Yes, it’s a whole fragment. However, does it have to imply that Jesus was referring to anybody else? Surely not!! Pure excitement!

—

Today’s Secondary Sources:

Harvard Professor Finds Scrap of Papyrus Suggesting Jesus Was Married

A reference to Jesus’ wife?

Mr. and Mrs. Jesus? What did the earliest Egyptian Christians believe?

A Faded Piece of Papyrus Refers to Jesus’ Wife

The Inside Story of a Controversial New Text About Jesus

4th century Coptic text fragment mentions the wife of Jesus.

Coptic Text Mentions Jesus’ Wife

And the day’s not even over yet!

Esther and Joseph: beautiful people

Rachel Held Evans has commented on Esther, and wishes a different interpretation than Driscoll’s. Here is one Jewish interpretation,

In particular, the author of the book of Esther in part modeled his heroes on Joseph, as if to say: we can survive in the Diaspora if we act like our forefather Joseph. The plot of his story contains numerous parallels to that of Joseph’s story. Consider the following:

In case these parallels were lost on any particularly obtuse readers, the author included a few lines guaranteed to bring the Joseph story to mind. read the rest here

But in addition to this we read that Esther was יְפַת-תֹּאַר, וְטוֹבַת מַרְאֶה beautiful in form and fair in appearance, while Joseph was יְפֵה-תֹאַר וִיפֵה מַרְאֶה beautiful in form and beautiful in appearance. This he inherited from his mother who was יְפַת-תֹּאַר, וִיפַת מַרְאֶה also.

Esther had this in common with Joseph that her beautiful appearance made her vulnerable to the desire of a foreigner. Joseph was beautiful and desired by Potiphar’s wife. Esther ended up in the king’s harem while Joseph landed in prison. Both subsequently achieved power through their intelligence and were able to serve their own people.

Others who were labeled as beautiful in the Hebrew Bible are David, Absalom, Abigail and Tamar. For Absalom and Tamar this lead to an unhappy ending, but for David and Abigail it was perceived as a good thing. For Joseph and Esther beauty brought them to the attention of the powerful, and although this lead to misfortune, they were able to survive the initial misadventure and live to see a positive resolution.

Perhaps Driscoll and co. would not like the Hebrew Bible very much, since heroes are sometimes beautiful and sometimes strong, or both; and heroines are the same, sometimes beautiful and sometimes strong, and sometimes both.

Perhaps we will soon be able to read on Rachel’s blog a rabbi’s response to Driscoll’s interpretation.

150 years since Antietam

22,717 killed, wounded, or missing after one day of vicious battle – the bloodiest day in the history of the United States.

Lincoln at Antietam.

“Bloody Lane”

Casualties near the church of the pacifist Dunker sect (Sharpsburg, Maryland)

First page of Emancipation Proclamation. According to Richard Sltokin’s Long Road to Antietam, the Union victory at Antietam created the political climate that allowed Lincoln to issue the Proclamation.

Catholic Priests in Poland Launch Magazine Focused on Exorcism

From AFP report:

Exorcism boom in Poland sees magazine launch

WARSAW — With exorcism booming in Poland, Roman Catholic priests have joined forces with a publisher to launch what they claim is the world’s first monthly magazine focused exclusively on chasing out the devil.

"The rise in the number or exorcists from four to more than 120 over the course of 15 years in Poland is telling," Father Aleksander Posacki, a professor of philosophy, theology and leading demonologist and exorcist told reporters in Warsaw at the Monday launch of the Egzorcysta monthly.

Ironically, he attributed the rise in demonic possessions in what remains one of Europe’s most devoutly Catholic nations partly to the switch from atheist communism to free market capitalism in 1989.

"It’s indirectly due to changes in the system: capitalism creates more opportunities to do business in the area of occultism. Fortune telling has even been categorized as employment for taxation," Posacki told AFP.

"If people can make money out of it, naturally it grows and its spiritual harm grows too," he said, hastening to add authentic exorcism is absolutely free of charge.

Posacki, who also serves on an international panel of expert Roman Catholic exorcists, highlighted what he termed the "helplessness of various schools of psychology and psychiatry" when confronted with extreme behaviors that conventional therapies fail to cure.

"Possession comes as a result of committing evil. Stealing, killing and other sins," he told reporters, adding that evil spirits are chased out using a guide of ritual prayers approved by Polish-born pope John Paul II in 1999.

"Our hands are full," admitted fellow exorcist and Polish Roman Catholic priest Father Andrzej Grefkowicz, revealing exorcists have a three month waiting list in the capital Warsaw.

Priests performing exorcism also work with psychiatrists in order to avoid mistaking mental illness for possession, he said.

"I’ve invited psychiatrists to meetings when I’ve had doubts about a case and often we’ve both concluded the issue is mental illness, hysteria, not possession," he said.

According to both exorcists, depictions of demonic possession in horror films are largely accurate.

"It manifests itself in the form of screams, shouting, anger, rage — threats are common," Posacki said.

"Manifestation in the form or levitation is less common, but does occur and we must speak about it — I’ve seen it with my own eyes," he added.

With its 62-page first issue including articles titled "New Age — the spiritual vacuum cleaner" and "Satan is real", the Egzorcysta monthly with a print-run of 15,000 by the Polwen publishers is selling for 10 zloty (2.34 euros, 3.10 dollars) per copy.

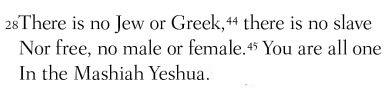

Gal 3:28 – Poetry (and Translated Poetry) and Play

………………………………..οὐκ

ἔνι Ἰουδαῖος οὐδὲ Ἕλλην οὐκ

ἔνι δοῦλος οὐδὲ ἐλεύθερος οὐκ

ἔνι ἄρσεν καὶ θῆλυ· πάντες γὰρ

ὑμεῖς

….εἷς

ἐστε

ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ

………………,…………………….………..Not

instances of Jews, not Hellenes, Not

instances of slaves, not freeds, Not

instances of boy and girl. After all, each

of you all and every one of

….you

is

in the Anointed, in this one Joshua

—-

Play seems to be what Paul is doing with his words. His lines are poetic, creative, constructive. Play, in English, is open, is almost full of frivolity or laden only with lightness and engaged fully in effortlessness — as in child’s play.

Play, nonetheless, can be ambiguous. Beyond mere playfulness, wordplay can leave it to the reader to interpret. Or play with words can be suggestive to the reader of new possibilities. And multiple ones, unconventional ones. How about we play with some would-be technical phrase for this phenomenon? How about we make it less poetic sounding and use technical Greeky and Greekish language, like “hermeneutic wiggle room” for this interpretive meaning of play?

Play, likewise, can be powerful, as in a well-performed play. As actors, players, might perform and interpret what a playwright has written, so audiences must and do respond. The theater is a place of social construct, of deconstructionism in a safe place that mirrors the real world but that insists on real change on the stage that might also transform life beyond it. How many of us have heard, even perhaps in Shakespeare’s play, from some actor’s mouth, from one Jaques or another, these lines? and how many of us have believed them for our own world as if that’s all there needs to be?

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;