Year of Biblical Womanhood

I wasn’t going to read this book, at least not right away – but that was before Kathy Keller and Mary Kassian reviewed it. How could I know if their reviews were honest. So, yes I have read it, and enjoyed it.

First, to complain about the hermeneutic in the book seems a little strained. There isn’t a lot of that, and it appears very late in the book. And yes, I felt a little uncomfortable at first when Rachel settled in to a Martha Stewart cookbook early on. But the story grew on me. And when Rachel failed to sew a dress, I groaned inwardly. This was my life, my upbringing, to bake bread, to make jam, to can peaches. I also sewed all my own clothes, and most of those of my children, from the age of 12 to 32. So, at first, I felt a little uncomfortable with some pages of the book. I thought to myself, perhaps she doesn’t know how much time some of us invested in sewing all our clothes, in baking our own bread.

However, Rachel’s engagement with the project quickly grew on me. I was fascinated with the other women she interacted with and I saw her personal growth as she went to Bolivia, as she read Kristof and WuDunn. I was particularly touched at the scene where she mourned for Jephthah’s daughter. I was impressed with the way she wove together contemporary expressions of biblical womanhood, stories of lesser known women in the Bible, and the real lives of Amish, Jewish, Bolivian women and second wives.

In short, there could be many valid several reasons why Keller and Kassian wrote the kind of reviews they did. The obvious one is that they are both complementation, and not egalitarian, as Rachel is. Although they disagree with the “hermeneutic,” I think the real reason is that they see this book as having enormous influence in demonstrating that a Christian couple can be happy in an egalitarian marriage. It’s really about “Team Dan and Rachel.”

If you could be a full partner in a marriage, and be loved by your spouse, why would you want the experience of Kathy Keller,

My first encounter with the ideas of [male] headship and [female] submission,’ she writes, ‘was both intellectually and morally traumatic.’ Yet Keller came to adopt the view that men and women have different roles in marriage and ministry, and that fulfilling such roles pleases God and leads to greater personal fulfillment.

I think what Rachel demonstrates is that one can have great personal fulfillment without the trauma. I am not sure that trauma ought to be an essential part of a Christian marriage. I experienced a lot of trauma, and I don’t believe that it pleased God in the tiniest way. Nor did it fulfill me in any way.

So, in my view, it is not the hermeneutic, but the sense of purpose, commitment and personal fulfillment which exudes from Rachel Held Evans,that makes this an important book for complementarians to rebutt.

Steiner’s thoughts about us, in his “Poetry of Thought”

Some time ago, we announced that George Steiner’s book The Poetry of Thought: From Hellenism to Celan was on its way to bookstores everywhere. Yesterday, I quoted a bit in a comment after the blog post from the Preface of that book. Today, I would like us to see a longer quotation up through the penultimate page of the book. It’s a quote of Steiner’s thoughts about us.

But first I’d like to say how odd I find it, how ironic, that those who praise poetry tend do so with prose. Remember Sir Philip Sidney’s The Defense of Poesie? And then a new acquaintance of mine lent me William A. Dyrness’s Poetic Theology: God and the Poetics of Everyday Life, which starts: “This book seeks to connect poetry and theology. It probably ought to have been written in poetry. But if it were, the poets would not read it because it was theology, and the theologians would not read it because it was poetry. And so it is written in the pigeon-toed prose of theology — a dog barking at the moon.” And quite frankly, this writer would actually elevate himself with this metaphor, because the book is worse than a howl if you ask me. And talking about its style.

Style is what Steiner gets at. Yes, he’s writing prose. Yes, it’s not so poetic and is often blunt, prosaic. “The point I have been trying to clarify is simple:” That’s the first line of page 214, the page where I find the quotation that I’m about to share with all of us below. On the same page, he has gone on: and he says, speaking of “Thought in poetry, the poetics of thought,” that “Their means, their constraints are those of style.” Steiner’s own style, which we ought to be paying attention to when he’s thinking and writing about that for us to read, reminds me of David Markson’s in Reader’s Block. There are so very many many quick little biographies, human stories, near name dropping for the informed. Given Steiner’s obvious interest in people, won’t we find it interesting then that he seems to be paying attention to us? Yes, that’s right. Watch what he writes as we pay attention to how he writes about his book’s “readers” and fascinatingly about readers of “the anti-rhetoric of the blog”:

I have suggested that this conception of language as the defining nucleus of being, as the donation, ultimately theological, of humaneness to man is now in recession. That neither in its ontological status nor in its existential reach the word retains its traditional centrality. In many respects this little book, the interest and focus it hope for from its readers — statistically a tiny minority — the vocabulary and grammar in which it is set out, are already archaic. They relate to the monastic arts of attention in, say, the early Middle Ages or the Victorian library. They accord poorly with the reduction of literary texts on screens or the anti-rhetoric of the blog. The mere survival of an essay depends on its availability online. The future of uncontrollably overcrowded, costly storage in public and academic libraries is increasingly questionable.

The new technologies pluck at the heart of speech. In the United States, eight- to eighteen-year-olds log about eleven hours of daily engagement with electronic media. Conversation is face-to-face. Virtual reality occurs within cyberspheres. Laptops, iPods, cell phones, email, the planetary Web and Internet modify consciousness. Mentality is “hard wired.” Memory is retrievable data. Silence and privacy, the classical coordinates of encounters with the poem and the philosophic statement, are becoming ideologically, socially suspect luxuries. As the critic Crowther puts it: “The buzz inside and outside your head has murdered silence and reflection.” This could prove terminal, for the quality of silence is organically bonded with that of speech. The one cannot achieve full strength without the other.

This does not mean that fine poetry and poetry of an intellectual, even explicitly philosophic concern is not being produced. Geoffrey Hill’s sensibility is profoundly consonant with the values of theology and political philosophy. Anne Carson’s experiments, at once forbidding and poignant, work northwards of Celan….

They don’t snitch, don’t sue, don’t destroy our democracy

When Women Take Over Democracy: A Humorous Page on How Men Imagine that Reversal

from Aristophanes’s play, “Women in Parliament” or Έκκλησιάζουσαι (also known as “The Assembly Women”), Written 390BCE, Translated by George Theodoridis ©2004

454

Chremes:

And he went on and on about all this, praising them. Gave a whole eulogy on them! They don’t snitch, don’t sue, don’t destroy our democracy… lots of other great virtues.

Blepyrus:

And what did he propose?

Chremes:

That the city be turned over to the women. It was thought that this was the only thing the city hasn’t ever tried.

Blepyrus:

And this proposal passed?

Chremes:

My words exactly. Absolutely!

Blepyrus:

And these women are now in charge of everything that we were in charge of?

Chremes:

Yep. Exactly right. They’re in charge.

460

Blepyrus:

So… instead of me going to court, from now on it’ll be my wife?

Chremes:

Nor will you be raising your children any more. Your missus will be in charge of that.

Blepyrus:

So… I won’t need to moan and groan every morning, worrying about our daily bread?

Chremes:

By Zeus, no! Oh, no, mate! From now on, it’s the wife who’ll be doing all the worrying. No need to moan, groan or worry about a thing. Just stay home and…

Blepyrus farts.

…fart all day!

Blepyrus:

Hmmm. I… I fear for us, you know? I fear that for men of our age, when these women take over they’ll force us… they’ll force us to… well, you know, to…

Chremes;

To do what?

http://bacchicstage.wordpress.com/aristophanes/women-in-parliament-2/

religious USA election day blogposts

Rachel Barenblat has up “Election week Torah” asking, “Does this bit of Torah [Deuteronomy 17:14-20] have any bearing on how you think about our government today?”

And she offers “A [Torah] poem, and a few links, for Election Day.”

Rachel Held Evans writes “Let us put away our swords and our sound bites,” making a “Call to worship,” sharing a “Prayer for the election,” giving an “Invitation to the table,” and sharing a “Communion liturgy.”

And she asks, “What thoughts and prayers are on your hearts today?”

Brian LePort wants to know “Is Christ divided on Election Day?”

He posts a Brian Zahnd riff of I Corinthians 1:13.

Balinese Citrus, Greek Virgins, Hebrew Dogs: Part 2

In Parts I and III of this III-part series of posts, I wanted to emphasize the fact that languages (such as ordinary Indonesian and biblical Hebrew) are translatable. But “translation” need not be reduced to the either/ or binary of “formal equivalence” vs. “dynamic equivalence,” a reductive essentializing that allows for no other options. Rather, the translator as another human being, can overhear what’s going on in the Indonesian culture and in the Jewish culture, for example. And the translator can use words that mark her or his translation as understanding or getting the points of the Indonesian flavors or the Jewishnesses of the expressions. Thus, “jeruk Bali” although it refers to a fruit that most know as pomelo when speaking English gets the locality of Bali and the culture of the Balinese there.

Hence, although “כלב” around the temple may be understood in the context as some sort of counterpart to a “זנה”, the former phrase suggests a lowly dirty canine, a mere dog. And English expresses “dog” aptly and ably.

—

Now in this Part 2 of the series, let’s consider something else. Let’s consider how English language translators often impose their own limitations on the translated language, say classical or LXX or New Testament or post NT Greek.

Most texts of the ancient world (of old old old Greece) use context well enough to point to meanings and to references of specific words. This allows those lexical items to carry vast ranges of meaning or, to say it another way, to have multiple and even all-related meanings. Lots of words also have gendered and sexed and sexualized meanings as part of their, if you will, single meaning. In other words, the Greeks had play in their words. (By “play” I also have play in my English: play can mean playfulness, and interpretive wiggle room, and performance as in what a playwright and a director and an actor and set makers and the chorus and the orchestra and the audience all perform together.) English translators of Greek words have tended to reduce the Greek words that appear much in sexualized context to only sexualized meanings.

I’m thinking now of English translators of the Greek-language translation of the Hebrew of “The Book of Isaiah ( ספר ישעיה).” The Greek word παρθένος is chosen by Jewish translators some 5 times for 2 Hebrew phrases. And most English translators of that reduce the Greek, in English, to something related to virginity, to sexually chaste and sexually pure sexual girls, to virgins. Granted, the Greeks before their word is appropriated by, say the writer of the gospel of Matthew, were not part of any Jewish/ Christian translation difference. “Isaiah prophesied of a maiden. No, Mother Mary is the Virgin of Virginity.”

But it’s not just Bible translators from Greek to English that have trouble. For example, when translating the play Hecuba by Euripides, translators from Edward P. Coleridge (1891) to George Theodoridis (2007), have reduced παρθένος to “maiden,” when the word refers twice to Polyxena (who is Multiplyforeign). Well, at least they haven’t reduced παρθένος to some religious sexual matter, to “virgin” of virginity. And yet, the story, the context, the Greek lore, the vast culture of Homer and Homeric epics is fraught with sexuality. To see Polyxena as she’s being stripped and sexually exposed and publicly humiliated and abused by the unsheathed sword of a man, to see her in contrast to her sister, to Hecuba’s other daughter, is to see how stressed is her virginity. The word παρθένος is vast. In the play, it has much play.

And so when we read what English translator Anne Carson has to say, how she ably and aptly translates this vastness, we get the fact that the Greek “Virgin” is not all a girl is. Carson notes the profundity, the vastness, of humanity in the Greek. And, in her Preface to her translation of Euripides’s play Hippolytos, she writes of the stress on sexualization and on objectification and essentialization of words, but she notes the agency of the Greek and the play of their language. And she reminds us readers that our English may be as vast or at least as capable as the old Greek of conveying the depths and the width:

Aidos (“shame”) is a vast word in Greek. Its lexical equivalents

include “awe, reverence, respect, self-respect, shamefastness, sense

of honor, sobriety, moderation, regard for others, regard for the

helpless, compassion, shyness, coyness, scandal, dignity, majesty,

Majesty.” Shame vibrates with honor and also with disgrace, with

what is chaste and with what is erotic, with coldness and also

with blushing….

Shame is a system of exclusions and purity that subtends Hippolytos’

religion. Interesting, then, to notice the presence of a bee

within his private religious space. For there is some evidence that

the bee, in its role of busy pollinator, was associated with Aphrodite’s

cult. And you will hear the chorus make a direct comparison

between Aphrodite and the bee later in the play, in a choral

ode celebrating the unavoidability of Eros (580–636/525–564). So

you might begin to wonder about Hippolytos’ simplicity….

And the fact that in epic poetry the word aidos is used in the plural

(aidoia) as a euphemism for the sexual organs (Iliad, 2.262).

These sexual and erotic strands form only part of the word aidos,

but it is a part that Hippolytos edits out. He edits Artemis too.

Her sexlessness reminds him of his own chastity; he idolizes it.

Her prestige as mistress of the hunt coincides with his favorite activity;

he makes it a form of worship. Her epithet parthenos (“virgin,

maiden, girl”) is used by him as if it named Artemis to a different

species than the female race that he denounces (“this counterfeit

thing—woman?” [684ff/616ff ]).

So picture, with me, going to the Parthenon in Athens. And then strolling a few steps over to the Erechtheion. Let’s have a seat and ponder. Are these representations, statues, of perpetual viginity? Or might these Greek girls, okay Hellene maidens if we must, might these Greek girls be vastly more than sexual objects in relation to not men? And is our English so limited, for translation, that they are merely virgins of Greece?

—

So just to summarize as if to make clear:

Part I of this series suggests that English is powerful enough to go beyond our familiar word “pomelo” to describe how Indonesians and many Malays see the Balinese fruit.

Part III sends us over to the analysis of Harry McCall, who shows us that English really does best when it carries across a biblical phrase as “dogs.”

Part 2 challenges English translators who reduce a Greek noun for girls to their would-be necessary virginity whether for religious or for male-sexual purposes. If the vastness of other Greek words can be conveyed by English words such as “shame,” then the vastness of the Greek word parthenos can be so conveyed as well.

Balinese Citrus, Greek Virgins, Hebrew Dogs: Part III

Suzanne, co-blogging with all of us here at BLT, made me aware of an interesting post on translating dogs from biblical Hebrew into English. It includes good examples of how Dynamic Equivalence translation sacrifices Hebrew culture just to make English readers feel like they’re getting the text in their own not-so-Hebrew culture. Are Hebrew dogs really humans, men, male prostitutes?

Blogger Harry H. McCall, CET calls the result a mistranslation and gets the credit here. The comment thread so far is interesting, although nothing yet about σκύβαλα.

—

Balinese Citrus, Greek Virgins, Hebrew Dogs: Part I

Growing up in Vietnam, I enjoyed eating and sometimes just playing with the big bưởi that grew on and fell from trees in the yard near my friend’s house. But when I moved to Indonesia in my mid teens, I learned that bưởi are actually called jeruk Bali. Later, as a college student in the USA, I discovered that the English term for this fruit is pomelo, which is likely what was crossed with the mandarin or the tangerine, to make the orange, which my Dutch friends don’t refer to this same fruit by a color (i.e., orange) but by a place (i.e., China), and so the Hollanders call the fruit sinaasappel. But in North America the Chinese apple is the pomegranate, which is neither an apple really nor much of a pomelo. And the blood orange, which is not orange in color but is closer in color to the pomegranate is a mutation of the orange, likely.

So how do we translate these terms from one language to another? What if “orange” in English doesn’t mean the color when referring to the fruit? What if “blood” in English doesn’t mean the body fluid that carries oxygen and nutrients to bones, brain, organs, and flesh and that washes away diseases and germs; what if it simply means the red color of such a fruit?

What if translators are led astray by the same words with different referents and various absolutely undynamic, unequivalent meanings? What if they’re Bible translators? “Such words usually mean completely different things,” warns Joel Hoffman when noting how “How Similar Words Lead Bible Translators Astray.” The word “bank,” he says, in “river bank” is not the same word that’s in “money bank.” Nor, he goes on, does it help that “the ‘nuclear’ in ‘nuclear family’ and in ‘nuclear energy’ comes directly from the word ‘nucleus’.” And so we remember that the mandarin that one eats is not the Mandarin that one speaks.

What I’d like to say late in this post is that there’s an alternative to Bible translators either being led astray by “similar [same] words” or not being led astray.

When translators pay attention to culture, to insider plays on words, on words like “jeruk Bali,” then there’s no temptation to rob the words of their play in translation. Let me give an English text to translate and then a Dutch one. Let’s imagine translating the English to Vietnamese and the Dutch to Hebrew. Whether you know English well or Dutch at all (or Vietnamese or Hebrew), I think you can get what I mean.

Here’s the English bit from page 82 of The proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, Volume 14, Part 1, published in Sydney in the year 1890 for information collected up through 1889:

Notice how the author(s) call the fruit in English “pimplenose.” This is their alternative, funny word, for “pomelo.” Now how would you say any of that, plus “jeruk Bali” in Vietnamese? Would you call the three words all “bưởi”? They all are the same. They’re all the same just as “money” is the same for “money bank” and for “money bank.” But because, in English, the fruit is given different names, and because one is descriptive, as the Indonesian word is, then why shouldn’t the Vietnamese translation be as descriptive? Well, there’s no reason the Vietnamese language couldn’t handle these funny distinctions (i.e., “pimple” and “nose” and “jeruk” and “Bali”). In fact, if the translator just ignores the word play, the adjectival variations, well, it’s no longer a real translation of English and of Indonesian at all. The culture of metaphor gets lost. The Vietnamese reader or listener to just bưởi might “understand” clearly which fruit is being discussed, and yet all the peculiarities of the English fruit or the Indonesian fruit would be squeezed out.

Ready for the Dutch? It’s from the 1895 book by C. J. Leendertz entitled, Bali en de Balineezen: Een en Ander over Land en Volk:

In de nabijheid der erven worden vele vruchtboomen aangekweekt. Zoo heeft men hier den mangga, den manggistan, de voedzame pisang, maar bovenal de pompelmoes (djeroek bësar), welke op Bali eene bijzondere grootte heeft en uitstekend van smaak is. Deze vrucht wordt als vorstelijk geschenk aangeboden en is dan tevens een teeken van vredelievende gezindheid.

Ook de sirih behoort tot die planten waarmede de bevolking hare langage des fleurs spreekt. Zoowel mannen als vrouwen maken van de bladeren van deze klimplant gebruik en dragen die steeds in een zak welke boven den buikband om het lichaam gebonden is bij zich Bij het afleggen van bezoeken is het steeds gebruikelijk bij wijze van welkomstgroet de sirih aan te bieden Het is van alge meene bekendheid op welke wijze dit genotmiddel wordt gebruikt. De zoogenaamde pruim bestaat uit een sirih blad een weinig zuivere witte kalk en een stukje pinang noot of gambir. Als toegift en om den mond te reinigen wordt een kleine hoeveelheid fijngesneden tabak gebruikt. Gedurende het pruimen wordt het speeksel bloedrood welke kleur zich ook aan de lippen en het tandvleesch mededeelt. Vorsten en ho0ggeplaatste personen laten zich dan ook steeds een kwispedoor tëmpat loedah nadragen dat bij enkelen van goud d0ch bij de meesten van koper.

Now, if you read Dutch, then you know that I’ve given separate paragraphs, the first on the bưởi, aka the pomelo. But writer Leendertz calls the fruit “pompelmoes (djeroek bësar)” and goes on to explain that it’s “(large citrus), which in Bali has a special size and has an excellent taste.” (Use google translate if you will. But then you’ll discover that some call “pompelmoes” in English “grapefruit.” And then we have that problem of this not being “grape” if it is “fruit.” So we just go on, knowing that the English plays this way but that google translate avoided being “led astray” while nonetheless lost the potential fun of the languages, the culture of naming.) When you read that second paragraph, you may understand that it’s a discussion of something called “sirih,” which under certain circumstances yields something that’s “bloedrood.” (But you may have gathered that this is no sinaasappel, or Chinese apple in Dutch, which in English is called an orange, or even a blood orange.)

I do want to show you now what I had early this morning for breakfast. Here in Texas it’s a Texas ruby red grapefruit.

There’s no need to worry the translator with the fact that it can still be a Texas citrus even in, say Minnesota or Hawaii or Maine or Oregon or Vietnam or China. Or that it’s not really a “ruby” or not precisely “red” all the time (my iPhone flash helped some); it’s actually orange on the outside though not an orange in size. Or not a grape though still fruit. The point is that “Texas ruby red grapefruits” are not “pompelmoes” either but may be something like them. And translators need not worry about teetering between the either / or of being led astray or not if they will get the culture, the distinctive naming peculiarities, the necessary wordplay among the culture of North Americans called Texans.

And djeroek Bali are not bưởi or pomelos or pimplenoses. Jeruk Bali are Balinese Citrus.

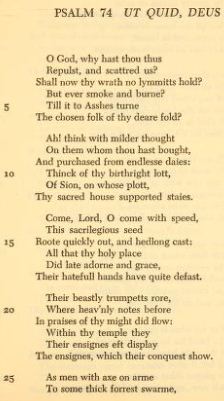

Psalm 74 translated by Mary Sidney Herbert

Of all the Sidney Psalms of Sir Philip and of Mary the Countess of Pembroke, one that stands out is Psalm 74. It deserves to be read. It calls for careful study. The entire poem is given below.

Notable lines and stanzas by Mary Sidney here, written in the world of men, are the following. Whereas the King James Version translators have:

Thou brakest the heads of leviathan in pieces,

and gavest him to be meat to the people inhabiting the wilderness.

she makes the senses of possession and of consumption a bit more embodied and explicitly so:

Thou crusht that monsters head

Whom other monsters dread,

And soe his fishy flesh did’st frame,

To serve as pleasing foode

To all the ravening brood,

Who had the desert for their dame.

She has the psalmist questioning God in English this way where the “seed” is “sacrilegious”:

The chosen folk of thy deare fold?

Ah! think with milder thought

On them whom thou hast bought,

And purchased from endlesse daies:

Thinck of thy birthright lott,

Of Sion, on whose plott,

Thy sacred house supported staies.

Come, Lord, O come with speed,

This sacrilegious seed

Roote quickly out, and hedlong cast:

All that thy holy place

Did late adorne and grace,

Their hatefull hands have quite defast.

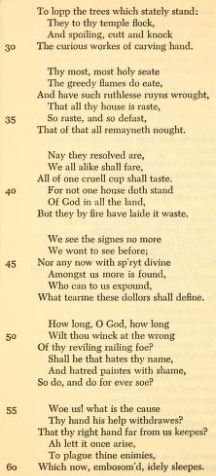

And look where she finds the hand of God, hidden, idle, asleep:

Woe us! what is the cause

Thy hand his help withdrawes?

That thy right hand far from us keepes?

Ah lett it once arise,

To plague thine enimies,

Which now, embosom’d, idely sleepes.

Hear the hierarchical language, the violence in it and the vulnerability crying out beneath it:

Thou then still one, the same,

Thinck how thy glorious name

These brain-sick mens despight have borne,

100 How abject enimies,

The Lord of highest skies,

With cursed taunting tongues have torne.

Ah! give noe hauke the pow’re

Thy turtle to devowre,

Which sighes to thee with moorning mones:

Nor utterly out-rase

From tables of thy grace

The flock of thy afflicted ones.

But call thy league to mynd,

For horror all doth blind,

No light doth in the land remayne:

Rape, murther, violence,

Each outrage, each offence,

Each where doth range, and rage and raigne.

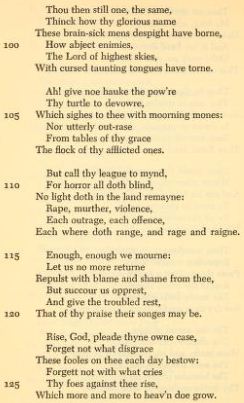

Again, how differently did the men translating for King James think. Here’s the whole Psalm (and below it a link to one place all the Sidney Psalms may be found and read and studied).

http://archive.org/stream/psalmsofsirphili00unse#page/174/mode/thumb

Robert Pinsky on the poetic biblical translating of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke

Anthologists, eager to compensate for patriarchal societies, sometimes appear to scrape up women for inclusion in their books. No apology is required for Mary Herbert’s accomplished, inventive work as a translator. Her version of “Psalm 52” uses rhyme— that barbarous, jangly departure from classical dignity—as part of an angry, urgent music. Interestingly, “Psalm 52” denounces those who are great and prominent, but false: a phenomenon that the Countess of Pembroke was well placed to observe.

Her version is less compact than the other great translation of her time, and more performative. The King James prose version has the force of simplicity and compression, a clinching denunciation. Mary Herbert makes the psalm into more of a song: an inspired rant, extravagant yet disciplined. (In her final line, “annoy” has become a weaker word in contemporary English than its root, which indicated hatred.) Comparing and appreciating the two translations, prose and poetry and appreciating both, can be a lesson in writing.

–Robert Pinsky, translator poet in Slate Magazine (the rest here)

Paul’s Beatitudes and Absence

In this post, I’m interested in language. Yes, language sometimes conveys reality, fact if you will. And yes some language is for fable. Surely most language mixes the two. Whenever somebody writes with language of power, of one’s authority over the other, especially to establish as reality the authority of the one over the other, then postmodernisms have taught us to pay attention. This is the hermeneutic of suspicion. Feminisms, likewise, get us noting when language is imbalanced, when it sexes the body fe-male making the male the default and the other sex, well, the other, the wo-man, the one different, aberrant, naturally deviant or mutated and therefore logically less than the male. This is the history of much of the language of the West.

So I’m interested in The Acts of Paul and Thelca. Maybe we would do well to pay attention to its language, to the implications of its language. Suzanne has done this in her post Assault and virtue. And Victoria has in her post Sexual Assault and Women’s Agency, or, Desire and the Disrupted Mob: The Story of Thecla and Trifina.

In reading “The Acts of Paul and Thelca” and Victoria’s post and another, Suzanne gets us paying attention to how girls (not so much boys) get Othered, even in how differently they are spoken of when victimized sexually:

[I]n challenging those who bewail the virtue of the young girl who was a victim of sexual assault, I ask you to consider the real pain of a child trauma victim, whether it is a boy or girl, raped, injured or invaded by instruments.

Victoria gets to some of the shock of the old story:

“To whose privy-parts” they did what?!?! This is some real sexual nastiness here: apparently, being killed by bulls who’ve had red-hot pokers applied to their balls is seen as a fitting end for an uppity emasculating bitch.

So I just want to get back to the language of the “flesh.” It’s such a crucial part of the imbalanced, unequal Acts of Paul on the one hand and of Thelca on the other. Early in the story, we readers understand that Titus does not know yet what Paul looks like. So the Greek story teller tells of the following: “τῇ εἰδέᾳ ὁ Παῦλος· οὐ γὰρ εἶδεν αὐτὸν σαρκὶ ἀλλὰ μόνον πνεύματι” or “a description of Paul’s personage, they as yet not knowing him in person, but only being acquainted with his character” or “what manner of man Paul was in appearance; for he had not seen him in the flesh, but only in the spirit.” When they do see him, they can’t decide whether this not really so handsome man is, well, a man like them or an angel. (I’ll spare you the description so you can just read it for yourself.)

But this angel language seems to come into play soon after, when Paul pronounces blessings in the house of would-be enemies. He says:

Μακάριοι οἱ καθαροὶ τῇ καρδίᾳ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ τὸν θεὸν ὄψονται.

μακάριοι οἱ ἁγνὴν τὴν σάρκα τηρήσαντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ναὸς θεοῦ γενήσονται.

Μακάριοι οἱ ἐγκρατεῖς, ὅτι αὐτοῖς λαλήσει ὁ θεός.

μακάριοι οἱ ἀποταξάμενοι τῷ κόσμῳ τούτῳ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ εὐαρεστήσουσιν τῷ θεῷ.

μακάριοι οἱ ἔχοντες γυναῖκας ὡς μὴ ἔχοντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ κληρονομήσουσιν τὸν θεόν.

μακάριοι οἱ φόβον ἔχοντες θεοῦ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἄγγελοι θεοῦ γενήσονται.

1:12 Blessed are the pure in heart; for they shall see God.

1:13 Blessed are they who keep their flesh undefiled (or pure); for they shall be the temple of God.

1:14 Blessed are the temperate (or chaste); for God will reveal himself to them.

1:15 Blessed are they who abandon their secular enjoyments; for they shall be accepted of God.

1:16 Blessed are they who have wives, as though they had them not; for they shall be made angels of God.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

Blessed are they that keep the flesh chaste, for they shall become the temple of God.

Blessed are they that abstain (or the continent), for unto them shall God speak.

Blessed are they that have renounced this world, for they shall be well-pleasing unto God.

Blessed are they that possess their wives as though they had them not, for they shall inherit God.

Blessed are they that have the fear of God, for they shall become angels of God.

(6.) Μακάριοι οἱ τρέμοντες τὰ λόγια τοῦ θεοῦ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ παρακληθήσονται.

μακάριοι οἱ σοφίαν λαβόντες Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ υἱοὶ ὑψίστου κληθήσονται.

μακάριοι οἱ τὸ βάπτισμα τηρήσαντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἀναπαύσονται πρὸς τὸν πατέρα καὶ τὸν υἱόν.

μακάριοι οἱ σύνεσιν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ χωρήσαντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἐν φωτὶ γενήσονται.

μακάριοι οἱ δι’ ἀγάπην θεοῦ ἐξελθόντες τοῦ σχήματος τοῦ κοσμικοῦ, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἀγγέλους κρινοῦσιν καὶ ἐν δεξιᾷ τοῦ πατρὸς εὐλογηθήσονται.

μακάριοι οἱ ἐλεήμονες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ ἐλεηθήσονται καὶ οὐκ ὄψονται ἡμέραν κρίσεως πικράν.

1:17 Blessed are they who tremble at the word of God; for they shall be comforted.

1:18 Blessed are they who keep their baptism pure; for they shall find peace with the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

1:19 Blessed are they who pursue the wisdom (or doctrine) of Jesus Christ; for they shall be called the sons of the Most High.

1:20 Blessed are they who observe the instructions of Jesus Christ; for they shall dwell in eternal light.

1:21 Blessed are they, who for the love of Christ abandon the glories of the world; for they shall judge angels, and be placed at the right hand of Christ, and shall not suffer the bitterness of the last judgment.

6 Blessed are they that tremble at the oracles of God, for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are they that receive the wisdom of Jesus Christ, for they shall be called sons of the Most High.

Blessed are they that have kept their baptism pure, for they shall rest with the Father and with the Son.

Blessed are they that have compassed the understanding of Jesus Christ, for they shall be in light.

Blessed are they that for love of God have departed from the fashion of this world, for they shall judge angels, and shall be blessed at the right hand of the Father.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy and shall not see the bitter day of judgement.

Μακάρια τὰ σώματα τῶν παρθένων, ὅτι αὐτὰ εὐαρεστήσουσιν τῷ θεῷ καὶ οὐκ ἀπολέσουσιν τὸν μισθὸν τῆς ἁγνείας αὐτῶν· ὅτι ὁ λόγος τοῦ πατρὸς ἔργον αὐτοῖς γενήσεται σωτηρίας εἰς ἡμέραν τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ, καὶ ἀνάπαυσιν ἕξουσιν εἰς αἰῶνα αἰῶνος.

1:22 Blessed are the bodies and souls of virgins; for they are acceptable to God, and shall not lose the reward of their virginity; for the word of their (heavenly) Father shall prove effectual to their salvation in the day of his Son, and they shall enjoy rest for evermore.

Blessed are the bodies of the virgins, for they shall be well- pleasing unto God and shall not lose the reward of their continence (chastity), for the word of the Father shall be unto them a work of salvation in the day of his Son, and they shall have rest world Without end.

I’m reading the Greek, and the translation Victoria gives (from Jeremiah Jones), and the English translation from M.R. James with considerations from variant texts including Coptic fragments of the story.

Go see again what the reference to angels (and men) is. And pay attention to the bodies of the virgins at the end of Paul’s Beatitudes.

Now we fast forward to one of the points in the story that Victoria points out. And I’m including what B. Diane Lipsett says about the Greek language at this point and how it can be translated. Notice how she points out that Paul is absent at this point in the story. And notice how the language goes at this point:

Αἱ δὲ γυναῖκες ἄλλων θηρίων βαλλομένων φοβερωτέρων ὠλόλυξαν, καὶ αἱ μὲν ἔβαλλον φύλλον, αἱ δὲ νάρδον, αἱ δὲ κασίαν, αἱ δὲ ἄμωμον, ὡς εἶναι πλῆθος μύρων. πάντα δὲ τὰ βληθέντα θηρία ὥσπερ ὕπνῳ κατασχεθέντα οὐχ ἥψαντο αὐτῆς· ὡς τὸν Ἀλέξανδρον εἰπεῖν τῷ ἡγεμόνι Ταύρους ἔχω λίαν φοβερούς, ἐκείνοις προσδήσωμεν τὴν θηριομάχον. καὶ στυγνάσας ἐπέτρεψεν ὁ ἡγεμὼν λέγων Ποίει ὃ θέλεις. Καὶ ἔδησαν αὐτὴν ἐκ τῶν ποδῶν μέσον τῶν ταύρων, καὶ ὑπὸ τὰ ἀναγκαῖα αὐτῶν πεπυρωμένα σίδηρα ὑπέθηκαν, ἵνα πλείονα ταραχθέντες ἀποκτείνωσιν αὐτήν. οἱ μὲν οὖν ἥλλοντο· ἡ δὲ περικαιομένη φλὸξ διέκαυσεν τοὺς κάλους, καὶ ἦν ὡς οὐ δεδεμένη.

9:10 Yet they turned other wild beasts upon her; upon which they made a very mournful outcry; and some of them scattered spikenard, others cassia, other amomus [a sort of spikenard, or the herb of Jerusalem, or ladies-rose], others ointment; so that the quantity of ointment was large, in proportion to the number of people; and upon this all the beasts lay as though they had been fast asleep, and did not touch Thecla.

9:11 Whereupon Alexander said to the Governor, I have some very terrible bulls; let us bind her to them. To which the governor, with concern, replied, You may do what you think fit.

9:12 Then they put a cord round Thecla’s waist, which bound also her feet, and with it tied her to the bulls, to whose privy-parts they applied red-hot irons, that so they being the more tormented, might more violently drag Thecla about, till they had killed her.

35 Now the women, when other more fearful beasts were put in, shrieked aloud, and some cast leaves, and others nard, others cassia, and some balsam, so that there was a multitude of odours; and all the beasts that were struck thereby were held as it were in sleep and touched her not; so that Alexander said to the governor: I have some bulls exceeding fearful, let us bind the criminal to them. And the governor frowning, allowed it, saying: Do that thou wilt. And they bound her by the feet between the bulls, and put hot irons under their bellies that they might be the more enraged and kill her. They then leaped forward; but the flame that burned about her, burned through the ropes, and she was as one not bound.

—

One of the things I’m hoping we notice here is how unequal the language, how it exacerbates and highlights the difference between males and their counterpart fe-males. In the Acts of Paul and Thelca, the one certainly seems less marked and more powerful than the Other.

Assault and virtue

Two memorable posts. First, Victoria has written at length about Thecla in Sexual Assault and Women’s Agency, or, Desire and the Disrupted Mob: The Story of Thecla and Trifina, concluding,

It’s so frustrating that Thecla’s story, like that of most of the Christian women saints, gets read as if it is all about virginity as a woman’s greatest (only) treasure, and sexual purity as a woman’s greatest (only) virtue. This story is about so much more than that! I’d read before that “virginity” in these ancient and medieval stories was a concept that functioned for the women in question more like agency and autonomy does for modern Western women today, because of the way that marriage worked in those days. But this is the first story I’ve read that made me really get it.

There’s more to Thecla’s story that I didn’t summarize here: there’s basically a happy ending, as she preaches both on her own, and with Paul, in various places. Then there’s an epilogue that has her going off to live as the local holy woman and monastic in the latter years of her life; until the devil stirs up another sexually-tinged plot against her among the doctors of the town (who are losing business because she’s a healer, too), and there’s a miraculously happy ending to that story too, as she is translated to heaven.

Her feast day is September 23rd (in the West, 24th in the East), and the Orthodox church reveres her as St. Thecla the Proto-Martyr, Equal to the Apostles. Although I don’t find these on any official lists, I think of her as the patron saint of women clergy, preachers, and missionaries; persons who suffer from sexual assault and all forms of sexual violence; and uppity women.

Trifina is not officially considered a saint, but she too shines as a figure of faith in this story. I think of her as a patron saint of those who protect and speak up for the vulnerable and the stranger, especially those vulnerable to sexual violence; of widows; of bereaved mothers; of adoptive mothers; and of converts.

In a post on a contemporary crime, Shirley writes,

A young girl was abducted at a bus stop and raped in a large city this past weekend. It probably happens every day but I want to tell you about this story because of what was said, and the meaning it conveys.

A group from the neighborhood tried to find the perpetrator, as it was apparently one of their girls who suffered this rape. “This is the worst thing you can do to a young girl,” one said, “to take away her virtue.”

It is, indeed, a very bad thing. It is traumatic. It is something that will change her life forever. However, they meant something far deeper than that. They meant that her worth had been taken away from her. A woman, or a young girl, is worth much more than that. She has worth far beyond her sexual organs, and her sexual being.

It is good to protect women, just as it is good to protect any other human being. But we can’t own them. American girls have rights over their own bodies. That right cannot be given to anyone else. It is hers alone.

A rape is a tragic thing, and we, too, hope the perpetrator is caught. We also hope that the girl is not devalued further because she has lost her virtue.

Men and women, little children – both boys and girls, can be victims of violence. But I think only females can lose their virtue. What a lot of nonsense!

I have been reading a lot on trauma, necessary for my job, and relevant to my own past. I work with children who have often experienced multiple surgeries and medical intervention. In some cases, a child can experience invasive surgery as a hostile assault. This can cause ongoing trauma. They are always relearning to trust adults. Or not.

I sat across from the parent, silently reading the diagnosis of autism, the useful and advantageous diagnosis that brings funds. But I also had to record the medical diagnosis. The next section refers to behaviour. Behaviour typical of autism? Not exactly. Its a glib response, to read that into everything. So I asked. What is the medical diagnosis, what about surgery? The story poured out. The slow descent into rebellion and withdrawal.

(In an aside, not all children experience medical intervention as violence. Some don’t. It’s hard to know what makes the different. Another pint-sized student at our school went to hospital today. She is the cheeriest little girl you could possibly meet.)

However, in challenging those who bewail the virtue of the young girl who was a victim of sexual assault, I ask you to consider the real pain of a child trauma victim, whether it is a boy or girl, raped, injured or invaded by instruments. Still, there is a case to be made for a certain kind of assault being particularly damaging. In the case where a close and trusted adult assaults a child, the betrayal may be worse even than the physical trauma. The child may also feel that by-standing adults are the real perpetrators of the assault – after all, they are allowing it.

In order to help trauma victims, it helps to understand trauma, what it really means, and not rant on about little girls losing their “virtue” – what a pile of crap. May God forgive those who hold such views. It is bad enough to suffer trauma, but to have that trauma endlessly misconstrued is no great blessing either. Physical trauma crosses gender boundaries. What is happening to the little girl that Shirley writes about is that certain people are retraumatizing her by saying that she has lost her virtue. That trauma is specific to girls. The retraumatization of females who are victims of assault occurs when they are in some way rejected by virtue of being victims of assault. Not that this can’t happen to males as well. Let’s stop retraumatizing victims, male or female. You would think that Christians could do better than this.

Carnival coming soon

I am in touch with friends and relatives in New York City, but only intermittently. Some have power at work but not at home, and others the other way around. Some have candles and wine, but no way to cook. Others haul gallons of water in their cars from home to work to be able to flush toilets. But they are running out of gas. Some are sitting in their cars near coffee shops, picking up on increasingly overtaxed wifi networks and others are metering out their cellphone minutes carefully. So we have decided to wait a few days to post the carnival.

Limiting access to the Sistine Chapel

From BBC:

There is an argument that it should be made as easy as possible for any pilgrim coming to Rome to see this room that has such a significant place in the Catholic world. And just a matter of weeks ago, in a newspaper article, [Vatican Museum director] Mr. [Antonio] Paolucci said it would be as “unthinkable” to limit access to the Sistine Chapel as it would be to limit access to the famous shrine at Lourdes.

But [Italian literary] critic, Mr. [Pietro] Citati takes a darker view, arguing that it is all about money. The Church makes a significant amount out of visitors to the Chapel and the other delights of the Vatican Museums. Everybody in the long queues in St Peter’s Square is paying more than 15 euros (£12.50) for a ticket. But it is possible though to avoid the masses if you can spare close to 220 euros for a private tour. Each involves about 10 people who are allowed into the Chapel outside the standard opening hours….

Writing shortly before his recent death, the art critic Robert Hughes recalled reading of the German writer, Goethe, visiting the Chapel 200 years ago. Back then the Sistine was “a place where one could be alone, or nearly so, with the products of genius,” Hughes wrote. “The very idea seems absurd, today; a fantasy. Mass tourism has turned what was a contemplative pleasure for Goethe’s contemporaries into an ordeal more like a degrading rugby scrum.”

a performance event: on defining “rape”

What sort of thinking has “sought to manipulate the definition of rape, introducing such terminology as ‘legitimate rape,’ ‘forcible rape,’ ‘honest rape,’ and more”? There was a poem, a sonnet, that answered the preceding question and also the following political statement/ rhetorical question before they were even asked: “Every candidate I know, every decent American I know condemns rape. OK, so why can’t people like Stephanie Cutter get over it?”

What “embodied, time-based events in word, sound, and movement, [whose] sonnets, moreover, represent opera as a performative text through which writing and reading, listening and looking, doing and un-doing, meaning and mis-understanding decline to the same verb”? And what active verb might that be? Listen, watch, and read. This is a performance event that seeks to undo the manipulation of the definitions:

Triple Sonnet of the Plush Pony

Part I

Do you think of your saliva as a personal possession or as something you can sell?

What about tears? What about semen? Linguists tell

us to use the terms alienable and inalienable

to make this distinction intelligible.

E.g. English speakers call both blood and faeces alienable on a normal day

but saliva, sweat, tears and bowels they do not give away.

Bananas and buttocks, in Papua New Guinea, belong to the inalienable class

while genitalia and skin of banana are not held onto nearly so fast.

Such thinking will affect how a word like rape is defined

or how sorcerers aim their spells or how you feel in your mind

when you address animals. Of course cows and cats,

sheep, pigs, donkeys, dogs and rats

depend on their owner to keep or dispose.

But your pony you cannot sensibly classify with those.

Lot’s daughters

A typical beginning PECS [Picture Exchange Communication System] user is a young individual who has not developed spoken communication and whose motivation to communicate is based on a preference for accessing tangible outcomes rather than social outcomes. In Phases 1 and 2, students learn to exchange a single picture with a communicative partner (CP) and to be persistent at getting and maintaining the CP’s attention.

the PECS user should be a persistent communicator in that she or he initiates the communicative interaction rather than waiting to be prompted to communicate and he or she persists in engaging the attention of a CP until the interaction is successful. ASHA

The unity and harmony, joined here with clear lines of authority and submission, defy the instincts of contemporary culture … Relations of authority and submission, lived out in unity and harmony – this is the model set for us by the Trinity Father, Son and Holy Spirit

Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up. 2 He said: “In a certain town there was a judge who neither feared God nor cared what people thought. 3 And there was a widow in that town who kept coming to him with the plea, ‘Grant me justice against my adversary.’

4 “For some time he refused. But finally he said to himself, ‘Even though I don’t fear God or care what people think, 5 yet because this widow keeps bothering me, I will see that she gets justice, so that she won’t eventually come and attack me!’”

6 And the Lord said, “Listen to what the unjust judge says. 7 And will not God bring about justice for his chosen ones, who cry out to him day and night? Will he keep putting them off? 8 I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. However, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?” Luke 18

The action of the daughters of Lot was an act of love and faithfulness to their father and to the need to give life, an honorable, even heroic act. In the ancestor stories in Genesis, in which God explicitly controls the opening and closing of wombs, the pregnancy of the daughters of Lot and the birth of Ammon and Moab are a reward for their extraordinary actions. Frymer-Kensky

When working with children who are non-verbal, one must decide whether the model relationship is that of authority and submission, or that of request and response. Is the adult/teacher the one who initiates and engages obedience and conformity, OR is the adult/teacher the one who stands by and happens to have what the child wants. The child must initiate a request or demand spontaneously, without prompting by the adult. The adult then responds by providing the desired item or action. If the adult responds by meeting the request, the child then learns that the request was functional, it got her what she wanted. It works. The child then learns to persist.

Which model for human relations best honours the humanity of the child, authority and submission, or initiation and response? In the PECS system, it is not only “initiation and response” but it is also “persistence.” If the adult is not paying attention, or is at a distance, the child must learn to persist.

If we work on the premise of Frymer-Kensky that the narratives about women are not about women, but are “a paradigm for understanding powerlessness and subordination” then we can look at what women in the bible did and see if it models the relationship of authority and submission, or that of initiation and response. Therefore, each and every time that a woman initiated a plea to God for a child, and was able to bear a child, it displays the proper relationship of initiation and response. The powerless initiates a request spontaneously and without prompting, and the Almighty rewards the request. This is the fundamental relationship between two persons or entities of differing power, that of initiation and response, initiation of a request by the less powerful, and response and reward granted by the more powerful.

This week, I spent time with the grade 6’s discussing the discovery of a planet in the Alpha Centauri system, one on one time reading with a grade 1 student, time training a team of support workers, time developing our website, and downloading apps, time with the consultants, who drop in and out, AND I spend time lying on the floor playing with the train.

In this model, there is no task too low, no level to which the person in power will not descend, there is no staying off the floor. The floor is something which I experienced in a relationship of authority and submission, unwanted contact with the floor, but now it is the level to which I will descend to play with, to respond and to grant a request. Sometimes, I even break off from a meeting with a group of support workers and consultants to lie on the floor and sort out the track, to provide the right pieces and model different ways of assembling track. They laugh at me, why am I on the floor?

Note: For those working with non-verbal children, we do have a wide variety of activities for these children, ranging from equipment for physical activities, a shopping and cooking program, computers, iPads, games and puzzles, pets, and so on. The train set – the train set really is there, but when I write, the train set becomes the metaphor for my interaction with the children. In reality, we find out what they love, what is their desire, their taste, their choice and attempt to offer a stimulating and varied program. These children are integrated into a regular class in a regular school and my room, which is lined with books, is also equipped to appeal to the non-verbal. It really doesn’t matter to me whether the child has a two word vocabulary, or wants to know about the habitable zone around Alpha Centauri B. You still get to initiate the conversation.

It’s now called 50 Nuance de Grey.

When it was in English only, British author E. L. James’s erotic bestseller was publicly denounced by some French readers as “Fifty Shades of Boredom.”

It’s now reportedly the “fastest selling book in French history.”

(And on the other side of the Atlantic, North American readers of English and of French are making James and her publisher even richer.)

Chacun voit midi à sa porte.

The Art of Finding Anything in the OT: Christianity and Mormonism

“As for the notion that anything can be found in the OT; I don’t think so.”

— Daniel Boyarin

“And just as the gold completely covers the acacia wood, so that one cannot see the wood except through the gold, even so do Christians see the Shared Scriptures only through the Christian Scriptures, which is why we name them the Old Testament, and our own scriptures the New Testament, and together they comprise our Bible.”

— Victoria Gaile Laidler

“The translating [Joseph] Smith undertook was an imaginative attempt to change history. This is a brilliant idea, and it was not the only time he did this. Also found in the Pearl of Great Price is the Book of Moses, wherein Smith rewrote parts of Moses’ life story, therefore changing this pivotal character’s story from the way it was originally described in the Bible.”

— Mike Furness

“But I shall make an account of my proceedings in my days. Behold, I make an abridgment of the record of my father, upon plates which I have made -with mine own hands; wherefore, after I have abridged the record of my father then will I make an account of mine own life.”

— Nephi (LDS.org ► Gospel Library ► Scriptures ► Book of Mormon ► 1 Nephi ► 1)

Daniel Boyarin does not yet see the face of American president candidate Mitt Romney in the face of the prophet Nephi. And Victoria, my co-blogger here at BLT, does not yet see in Nephi’s hand the hand of Christ or of John the Baptist or of Aristotle. But Neima Jahromi does in “Adventures in Mormon Art History.”

And Mike Furness sees in Joseph Smith a “prophet, seer and artist,” a translator of the Scriptures. Smith “claims to have not only seen, but spoken with, God and Jesus Christ, thus beginning his controversial and remarkably ambitious creation—The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

And now, still, the “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reveres and respects the Bible.” For the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, there is nonetheless more art, the art of finding more in the OT:

The Christian Bible has two divisions, commonly known as the Old and New Testaments. The Old Testament consists of the books of scripture used among the Jews of Palestine during the Lord’s mortal ministry. The New Testament contains writings belonging to the Apostolic age and regarded as having the same sanctity and authority as the Jewish scriptures. The books of the Old Testament are drawn from a national literature extending over many centuries and were written almost entirely in Hebrew, while the books of the New Testament are the work of a single generation and were written mainly in Greek….

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reveres and respects the Bible and affirms also that the Lord continues to give additional revelation through his prophets in the last days that supports and verifies the biblical account of God’s dealings with mankind.

- The stick of Judah (the Bible) and the stick of Joseph (the Book of Mormon) will become one in the Lord’s hand, Ezek. 37:15–20

- The Bible’s truthfulness will be established by latter-day scripture, 1 Ne. 13:38–40

- The Bible will be joined by the Book of Mormon in putting down false doctrine, 2 Ne. 3:12

- A Bible! A Bible! We have got a Bible, 2 Ne. 29:3–10

- All who believe the Bible will also believe the Book of Mormon, Morm. 7:8–10

- Elders shall teach the principles of my gospel, which are in the Bible and the Book of Mormon, D&C 42:12

- We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly, A of F 1:8

This is all very interesting and fascinating to me. The metaphor of translation, of Bible translation, as art and as imagination and as scripture making and as interpretation.

And so I am all the more intrigued by what my friend Courtney Druz has asked me:

“Are you pointing out that even the relatively straightforward translations in the Septuagint (not dealing with virgins, etc.) enact a radical displacement of the text, severing its ties with Jewish interpretive traditions and embedding it in Greek culture?”

Courtney, I confess I do not know what The Virgin is doing in the Septuagint. I confess I glossed over this in your question! I confess I don’t know what we’ve found when we find that the OT is translated as

διὰ τοῦτο δώσει κύριος αὐτὸς ὑμῖν σημεῖον ἰδοὺ ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἕξει καὶ τέξεται υἱόν καὶ καλέσεις τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Εμμανουηλ – Isaiah 7:14

It sure makes artwork of the opener of the New Testament. Matthew translates, interprets, when chapter 1, verse 23, “reveres and respects the Bible and affirms also that the Lord continues to give additional revelation through his prophets in the last days that supports and verifies the biblical account of God’s dealings with mankind.” Here’s that additional, with its additional translation:

Ἰδού, ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἕξει καὶ τέξεται υἱόν, καὶ καλέσουσιν τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Ἐμμανουήλ, ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον, Μεθ’ ἡμῶν ὁ θεός.

Which is also why it’s so fascinating today that Boyarin’s Jewish gospels contain the Jewish Christ. What can be found in the OT, in the NT, in the gospels, in the Church, in Jesus Christ, in all that’s beyond these?

Review: Testament Of Abraham

Testament Of Abraham by Dale C. Allison Jr.

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is a superb piece of scholarship on a non-canonical Jewish-origin text that really deserves to be better known. The story of Abraham’s encounter with the archangel Michael, his misapprehensions, delaying tactics, tour of heaven and earth, change of heart, encounter with Death, and eventual death is hilarious and fascinating. If Dr. Allison does not presently have plans to publish his translation and an abridged commentary in a more popularly (and financially) accessible version, I hope he’ll consider it!

Because as good as this book is, it is not for the faint-of-academic-heart. I skipped entirely over the text-critical notes (commenting on the various manuscripts in which the text has survived), and almost entirely over the superabundance of parenthetical references to other ancient texts (Jewish, Christian, Graeco-Roman, and others) with comparable words, themes, or ideas. I sounded out some of the Greek words and recognized some cognates, but was frustrated because I can’t actually read Greek and thus much of the detailed word-analysis was lost on me.

On the other hand, the introductory chapters which present some context for the text are excellent in their own right. The translation itself, with the long and short recensions presented in parallel, reads very well. The verse by verse commentary attends to the literary structure of the text and its intense intertextuality with scripture and with other ancient writings. It also provides judicious assessments of where Christian influences likely dominate, and engages with other contemporary commentary.

The Testament of Abraham was a delightful discovery for me this semester; and if this volume is typical of the series, the Commentaries on Early Jewish Literature will be indispensable to serious scholarship in the field.

H/T and thanks to Diglotting, whose review of this book came up in my search results for “Testament of Abraham.”

(cross-posted at Gaudete Theology)

Describing the Bible

This week in my church history class, we studied methods of biblical interpretation in the early church, and were given the exercise of trying out an allegorical, typological, or moral interpretation of Exodus 25:10-16. My punny co-blogger’s last post, in which he mentions in passing the question of how Christians should name the set of scriptural texts that comprise the Jewish bible, prompted me to take up this theme for my exercise.

Here is the text from the New Jerusalem Bible:

You must make me an ark of acacia wood, two and a half cubits long, one and a half cubits wide and one and a half cubits high. You will overlay it, inside and out, with pure gold and make a gold moulding all round it. You will cast four gold rings for it and fix them to its four supports: two rings on one side and two rings on the other. You will also make shafts of acacia wood and overlay them with gold and pass the shafts through the rings on the sides of the ark, by which to carry it. The shafts will stay in the rings of the ark and not be withdrawn. Inside the ark you will put the Testimony which I am about to give you.

And here is my allegorical interpretation, written for my Christian sisters and brothers:

In this passage, the ark represents the Bible. The acacia wood represents the Shared Scriptures. These scriptures were given by the LORD to the people of Israel, and our Jewish sisters and brothers name them the Bible, or in Hebrew the Tanakh. The gold represents the Christian Scriptures. Now both wood, and gold, come from God first, and are then worked by human hands. In the same way, the Bible is the work of human beings who were first inspired by God, and then “acted as true authors” in their writing of these sacred texts.

Just as the acacia wood is at the heart of this golden ark and provides its structure, even so are the Shared Scriptures at the heart of the Christian Scriptures, and provide their structure. And just as the gold completely covers the acacia wood, so that one cannot see the wood except through the gold, even so do Christians see the Shared Scriptures only through the Christian Scriptures, which is why we name them the Old Testament, and our own scriptures the New Testament, and together they comprise our Bible.

The four gold rings represent the four gospels, and the two rods running through them represent the two great commandments: You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and all your mind and all your strength, and You shall love your neighbor as yourself. For as Jesus taught us, it is from these two commandments that all the Law and the Prophets depend.

Finally, we see that the testimony of the LORD is not the ark itself, but is to be found inside the ark. In the same way, we must not confuse the Bible itself with the voice of the LORD, but rather, it is within the Bible that we can, with care and with prayer, hear the still, small voice of God.