The end of time and space …

When I was little, I was asked a riddle, “What is the beginning of eternity, and the end of time and space?” See the end of the post for the answer. I also noticed that the LORD was L’Éternel in French, my grandfather’s language. In German, the LORD is Der Ewige.

I finally decided to track this down. Here is Exodus 3:13-15 in several different translations, Hebrew, Olivétan 1535, Luther, 1545, and Mendelssohn, 1780 and finally Buber-Rosenzweig.

וַיֹּאמֶר מֹשֶׁה אֶל-הָאֱלֹהִים

הִנֵּה אָנֹכִי בָא אֶל-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל

וְאָמַרְתִּי לָהֶם, אֱלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵיכֶם שְׁלָחַנִי אֲלֵיכֶם;

וְאָמְרוּ-לִי מַה-שְּׁמוֹ,

מָה אֹמַר אֲלֵהֶם.

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים אֶל-מֹשֶׁה,

אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אֶהְיֶה;

וַיֹּאמֶר, כֹּה תֹאמַר לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל,

אֶהְיֶה, שְׁלָחַנִי אֲלֵיכֶם.

וַיֹּאמֶר עוֹד אֱלֹהִים אֶל-מֹשֶׁה,

כֹּה-תֹאמַר אֶל-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל,

יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵי אֲבֹתֵיכֶם

אֱלֹהֵי אַבְרָהָם אֱלֹהֵי יִצְחָק וֵאלֹהֵי יַעֲקֹב,

שְׁלָחַנִי אֲלֵיכֶם;

זֶה-שְּׁמִי לְעֹלָם,

וְזֶה זִכְרִי לְדֹר דֹּר.

Et Moseh dit à Dieu:

Voici, j’irai aux enfants d’Israël et leur dirai:

Le Dieu de vos pères m’a envoyé vers vous;

et s’ils me répondent:

Qui est son nom? Que leur dirai–je?

Et Dieu dit à Moseh:

Je suis qui suis Puis il dit:

Tu diras ainsi aux enfants d’Israël:

Je suis m’a envoyé vers vous.

Et Dieu dit encore à Moseh:

Tu diras ainsi aux enfants d’Israël:

L’Eternel, le Dieu de vos pères,

le Dieu d’Abraham, le Dieu d’Izahak, le Dieu de Jakob,

m’a envoyé vers vous.

C’est mon nom éternellement

et le mémorial de moi au siècle des siècles.

Mose sprach zu Gott:

Siehe, wenn ich zu den Kindern Israel komme

und spreche zu ihnen:

Der Gott eurer Väter hat mich zu euch gesandt,

und sie mir sagen werden:

Wie heißt sein Name?

was soll ich ihnen sagen?

Gott sprach zu Mose:

ICH WERDE SEIN,

DER ICH SEIN WERDE.

Und sprach: Also sollst du den Kindern Israel sagen:

ICH WERDE SEIN hat mich zu euch gesandt.

Und Gott sprach weiter zu Mose:

Also sollst du den Kindern Israel sagen:

Der HERR, eurer Väter Gott, der Gott Abrahams, der Gott Isaaks, der Gott Jakobs,

hat mich zu euch gesandt.

Das ist mein Name ewiglich,

dabei soll man mein Gedenken für und für.

Mosche sprach zu Gott:

wenn ich nun zu den Kindern Israels comme,

und sage ihnen

Der Gott eurer Väter sendet mich

und sie sprechen

Wie ist sein Name

was soll ich ihnen sagen?

Gott sprach zu Mosche :

Ich bin das Wesen, welches ewig ist !

Er sprach nämlich, so sollst du

zu den Kindern Israels sprechen, das Ewige

Wesen, welches sich nennt, ich bin ewig,

hat mich zu euch gesendet.

Gott sprach ferner zu Mosche

So sollst du zu den Kindern Israels sprechen

Das ewige Wesen welches sich nennt, ich bin ewig

Der Gott eurer Voraltern

der Gott Abrahams, der Gott Isaschs, der Gott Jakobs

sendet mich zu euch

Dieses ist immer meine Name,

und dieses soll mein Denkwort

sein in zukünftigen Zeiten

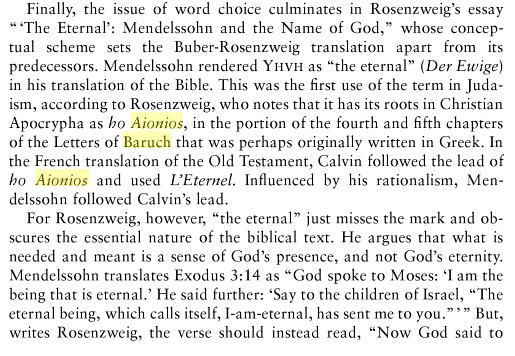

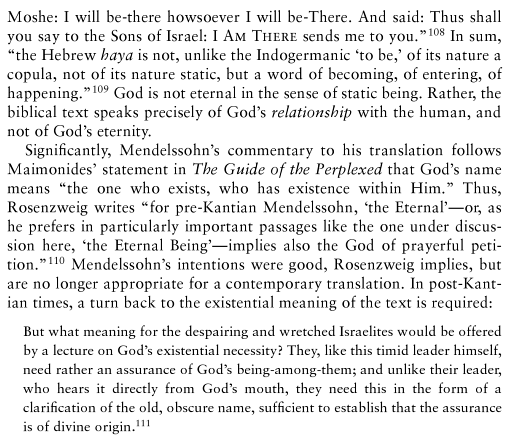

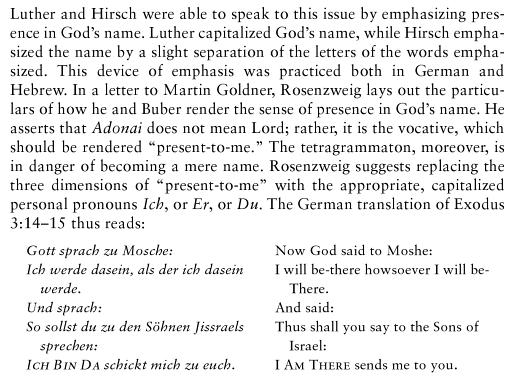

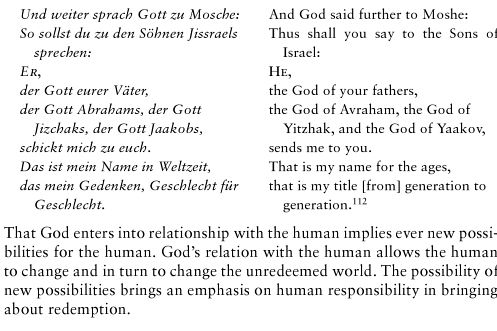

It seems that Olivétan was the first to use “L’Éternel” in a Bible translation and Mendelssohn followed that. However, he also wrote about the expression ho Aionios in the the Letter of Baruch. Here is a discussion of Rozenzweig’s response to the use of Der Ewige for God.

I am not sure if anyone else is interested in these things, but I am. It’s nice to have so many early Bibles online. I know the commentary mentions Calvin and not Olivétan, but Calvin did not produce a Bible translation. He did later write about l’Éternel in a commentary. I don’t know which influenced Mendelssohn. PS. And the answer to the riddle is “E.”

Women drumming

After thinking about wedding songs as the domain of women, I read here that drumming was also the exclusive domain of women in the Hebrew Bible. All references to hand drums, often called a tambourine or timbrel, mention women, Miriam, Japheth’s daughter, the maidens in Psalm 68, the young women who danced before the ark when it entered Jerusalem and so on.

All visual evidence, pots and vessels, statues and relief, portray only women as using the hand drum. I do hope that no men at the “Act like Men” conference were drummers, doing a feminine thing like that. It doesn’t appear that there were other kinds of drums for men in the Hebrew Bible. The men had to play a harp or lyre. Somebody let Driscoll know about that.

Of course, the early church had to eliminate the dancing and drumming of women, so that one thing that women did and men did not do, was made undoable. Of course, now it’s back. I talked to a man who attended the Act like Men conference, and the only thing he remarked on was how much fun it was to look at his new measure the decibels app and notice that safe levels were significantly bypassed. Typical that, playing with his latest mechanical toy. He was indeed “acting like a man.” Sorry, couldn’t resist.

Woman Translating Man? אָח : ἀδελφιδός :: “brother” : “brotherkin”?

How about the Septuagint translator(s) of the Hebrew Song of Songs if authored by a woman?

Was she also a woman, then, rendering the Hebrew into Hellene? And how would a female do that? What sort of Greek would she use?

NETS translator Jay C. Treat leaves open the possibility, conjecturing:

Its use in 5.9 and in 8.1, where it translates אָח (“brother”), shows that Greek Song is using this diminutive as a term of endearment. Its use may suggest that the translator was a woman. Because ἀδελφιδός must have sounded unusual in Greek ears, the NETS translation [by Treat himself] consistently renders it with a formal equivalent that sounds unusual in English: “brotherkin.”

What’s strange and perhaps unfortunate is how Treat so cleverly and consistently uses “brotherkin” as a supposed womanly “unusual” sounding diminutive term of endearment coinage, as if this is just what a woman (not a man) might do. He also keeps on referring to the Greek translator of the Hebrew by “he” and not by “she.” So Treat is more consistent in his own talk about the translator as a default man; and yet he wants to have her also a woman who doesn’t really know what good Greek sounds like, and he inflicts that on his English readers’ ears.

Is there scholarship and research on the sex of the Song of Songs LXX translator beyond Treat’s guess here based on one odd Greek phrase?

Tech Notes

I just can’t resist posting this pic of my daughter’s older Apple laptop. In my view, laptops are supposed to die with a whimper not a bang. This one was thrown outside and the flames were put out with a fire extinguisher. In other irritating incidents, the new OS on my iPad has made Kindle misfunction and about a third of my books won’t redownload, and the newest book I paid for on Kindle won’t download either. The Genius bar thinks this is Kindle’s problem, not theirs, but I don’t know how to access a Kindle help desk. Also my MacBook Air won’t connect with most wifi outside my own home. This restricts my posting when I am away from home. Sorry about the bitching, but this is life.

Song of Songs by Tremper Longman III

I have not been such a fan of commentaries, having been exposed to too many conservative ones, but this one  is a delight! Here is a good review of the book overall. The review does mention that he does not refer to Ariel and Chana Bloch’s book The Song of Songs: A New Translation with an Introduction and Commentary (New York: Random House, 1995), nor Renita Weems in C. Newsom and S. Ringe, eds., The Women’s Bible Commentary[Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1992], pp. 156-60). The only other question I have is was it really necessary to reference Keil and Delitzsch. They have such terrible views on women. (See there views on Gen. 3:16 here.) So those are my reservations. Otherwise it is really informative and considers a wide range of interpretation.

is a delight! Here is a good review of the book overall. The review does mention that he does not refer to Ariel and Chana Bloch’s book The Song of Songs: A New Translation with an Introduction and Commentary (New York: Random House, 1995), nor Renita Weems in C. Newsom and S. Ringe, eds., The Women’s Bible Commentary[Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1992], pp. 156-60). The only other question I have is was it really necessary to reference Keil and Delitzsch. They have such terrible views on women. (See there views on Gen. 3:16 here.) So those are my reservations. Otherwise it is really informative and considers a wide range of interpretation.

First, Longman supports the possibility that Song of Songs was at least in part written by women. He regards the book as a collection of poems, some of which could easily have female authors. After some discussion about female authorship, he writes, page 8-9,

It is not just women scholars who argue for this position; they are also joined by F. Landy and A. LaCocque. Indeed the latter quotes the former as he states his opinion that “the author of the Song was a female poet who intended to ‘cock a snook at all Puritans.'” In other words, according to both these commentators, the Song was written by a woman who was resisting social norms, including the idea that women should be receivers and not initiators of love.

Against the rising tide supporting the idea of female authorship of the Song, comes D. J. A Clines, always reading against the grain.”In a nutshell, his opinion is that the woman of the Song is the perfect woman from a male perspective, the ideal dream of most men, and thus a fabrication by men. He believes that the book was written by men in order to meet the need “of a male public for erotic literature.”

The most honest appraisal is that we do not know for certain who wrote the songs of the Song, a man or a woman, and in any case it is a collection of love poetry, whether by men, or women, or both. It strikes me, though, that Clines is the most egregious of these commentaries since his view relies on the supposition that no woman would have an interest in the kind of love that the beloved articulates.

So Longman just gives us the views of others, but identifies the male author theory of Clines as the least appealing. Longman later writes, page 15,

We begin with the woman because she is by far the most dominant presence in the Song. She speaks more frequently than the man, and, when the latter speaks, he often speaks of her. … The woman not only speaks more often but also initiates the relationship and pursues it. She frequently expresses her desire for the man; she even overcomes threats and obstacles to be with him.

And later, writing regarding the man, page 16, Longman reinforces mutuality,

He is desired to be sure, but he also desires her. She pursues him, but he also pursues her.

There is nothing in this commentary about Sappho, but much about Egyptian and Mesopotamian poetry. Much to appreciate in this book. This connects also with Bauckham’s chapter in Gospel Women on Female Power and Male Authority.

100 years of Swann’s Way

November 14th marks the hundredth anniversary of Swann’s Way, the first volume in Marcel Proust’s fabulous but challenging massive novel about time and memories: In Search of Lost Time.

In honor of Proust, French cultural agencies have sponsored special exhibitions and readings from Kiev to Paris. In the United States, events are focused in Berkeley, Birmingham, Boston, Coral Gables, New Haven, New York, and Providence.

But even if you do not live in these cities, you can still take part in the celebration of this amazing work of literature. On Thursday, Yale University Press officially publishes a new annotated edition of Swann’s Way by William Carter (revised from the Scott Moncrieff translation). Penguin has just released a hardcover edition of Lydia Davis’s fresh Swann’s Way as part of its cute (albeit gimmicky) “Drop Caps” editions. Naxos has just released a massive complete (120 CDs!) unabridged audio edition of In Search of Lost Time (if you order this currently outside of the EU from Amazon UK, this is a relative bargain, since without VAT it is a “mere” £229.59.)

And there are at least two web sites worth mentioning: Proust Ink and Radio Proust. Altogether, a special literary anniversary, and an excuse for rereading Proust.

Whose Lord’s Prayer? Whose Same Womb?

Suzanne’s post gives us context to consider “wombly feelings, family loyalty” as understood by “the brother and sister” who are “of the “same womb, biologically related,” children and then adults who experience “the supreme relationship in ancient times.” In this post, I’d like to take this familial relationship (i.e., the relationship of being out of “the same womb” with another individual) as a lens for reading Greek Isaiah 63 and for reading the Greek gospel versions of the Lord’s Prayer.

If we start only merely simply with the lens of common reading – of a common sense reading, say, of using the ubiquitous and popular and sort of crowd sourced wikipedia reading of the Lord’s Prayer, then we start in with the following rather common and ho hum usual:

The Lord’s Prayer is a central prayer in Christianity also commonly known as the Our Father and in Latin as the Pater Noster. In the New Testament, it appears in two forms: ….

Someone at anytime can “correct” the wikipedia entry, and yet let’s look at what it is today in English. The first language explicitly mentioned is “Latin.” Implicitly the important language, for sure, is English, which is what readers are reading and the writers were writing; and we English readers have to scroll down a significant way to see the Greek of Matthew’s gospel only, where we’re offered again the Latin with an audio link to hear only the Latin, followed quickly by the English translations.

The wikipedia writers/editors (which could be most any of us) start in by telling us wikipedia readers of the significance of the prayer: “a central” one “in Christianity.” Its name is commonly “the Our Father.” This is all fine and good unless you, the reader, are say Jewish and perhaps are a woman and a mother who’s experienced dominant culture and dominant sex abuses. I’m not trying to make my post here into a feminist one; nonetheless, I think we all have to see the dominant lens of the Patriarchy that predominates much of Western Christianity that uses English. It’s not necessarily that Christian sexist men wrote the wikipedia entry that we start reading above. It is that the sort of language used to define sacred prayers such as the Lord’s Prayer often goes unquestioned as the only language for the only possible view of Reality that there can be. (To correct the narrowness of the English wikipedia entry, one might try first reading the counterpart version in, say, modern Greek just to see how different it can be.)

Because I’m nearly out of time writing this this morning, I’m going to end my post rather abruptly. The burden I’m putting on us readers now is to go to the texts of the Greek Isaiah, which some of us have been reading through this year daily (led by Abram K-J blogger, here). Today’s reading is the beginning of the people’s recollection of the tender mercies of the LORD. Mid-week the reading is the beginning of the Prophet’s prayer to the LORD as “πατὴρ ἡμῶν.”

This is as striking in Greek (the translation of the Hebrew by Jewish brothers and sisters) as it is in the Hebrew. For one thing, the language is as maternal as it is paternal. Let me show the English translation of the Hebrew from The Inclusive Bible:

When the Hebrew was made into Hellene by Jews in the diaspora, the wombly ties that are in the original language are carried through to the Greek language. Isaiah is praying on behalf of his sisters and brothers to the LORD. In Hellene this prayer continues to emphasize as Suzanne puts it how “the brother and sister are adelphos, and adelphé, of the same womb, biologically related.”

Their prayerful appeals are to a God who is more than a father Abraham and more than a father Israel than the named patriarchs could be. This is the kind of Person who is profoundly and viscerally aroused, as with motherly instincts, for them.

When the earliest Jewish readers of the Greek gospels of Matthew and of Luke read the Lord’s prayer there, then there’s possibly not only an echo of the Greek Isaiah (I mean look at all the language referring to coming down from Heaven and to the Name of G-d in the Greek prayers in Greek Isaiah and in the two Greek gospels). There’s also possible in the Greek gospel versions of “πατὴρ ἡμῶν,” the idea of the wombly feelings of sisters and brothers of the same mother. Jesus is instructing the people in Israel, his sisters and his brothers that they may pray to “our Parent,” and this one in Heaven is profoundly aroused with motherly instincts.

wombly ties

I have been thinking a lot about Kurk’s post on Joseph and motherly instincts. Of course, this shows how little of the original culture shows through in English. The two women were both female, but only one had a biological link to the child. Joseph was Benjamin’s only brother of the same mother. The link is by the womb, but refers to a biological relationship, not a motherly relationship. Men had the relationship also, brothers had it, brothers and sisters had this relationship.

In Greek, the brother and sister are adelphos, and adelphé, of the same womb, biologically related. This is the supreme relationship in ancient times. The spouse, unless a passionate lover, as in Song of Songs, the spouse could be a throw away. Here is an instructive story,

Taking precautions against further resistance, Darius sent soldiers to seize Intaphernes, along with his son, family members, relatives and any friends who were capable of arming themselves. Darius believed that Intaphernes was planning a rebellion, but when he was brought to the court, there was no proof of any such plan. Nonetheless, Darius killed Intaphernes’ entire family, excluding his wife’s brother and son. She was asked to choose between her brother and son. She chose her brother to live. Her reasoning for doing so was that she could have another husband and another son, but she would always have but one brother. Darius was impressed by her response and spared both her brother’s and her son’s life.

Who was closer to her womb, apparently her brother. It was not about motherly feelings, but about family solidarity. But then even the eunuch has these feelings for Daniel. God for his people, mothers for children, brothers for brothers, these are the wombly feelings we find in the Hebrew Bible. I would suggest that sisters and brothers for each other, children for parents, parents for children, all the natural family ties, are the wombly feelings, not “motherly” feelings.

I don’t mean to downplay the difference in circumstance between men and women in Bible, but I do believe that in emotional makeup, men and women both, were to have wombly feelings, family loyalty. Here are a few examples,

And Joseph made haste; for his bowels did yearn upon his brother: and he sought where to weep; and he entered into his chamber, and wept there. Gen. 43:40

Thus speaketh the Lord of hosts, saying, Execute true judgment, and shew mercy and compassions every man to his brother: Zec. 7:9

And forgive thy people that have sinned against thee, and all their transgressions wherein they have transgressed against thee, and give them compassion before them who carried them captive, that they may have compassion on them: 1 Kings 8:50

Now God had brought Daniel into favour and tender love with the prince of the eunuchs. Dan. 1:9

Thus saith the Lord; For three transgressions of Edom, and for four, I will not turn away the punishment thereof; because he did pursue his brother with the sword, and did cast off all pity, and his anger did tear perpetually, and he kept his wrath for ever: Amos 1:11

Sappho and Song of Solomon

Now that linguistic data has suggested that the Song of Solomon was written in the 3rd century BC, some are looking closer at its structure as a wedding song, in the same genre as Sappho’s songs, and wondering if there was an influence. Here is a thought provoking post, and I suggest a look at this book which is online also. On page 26, there is this speculation,

Does Song of Solomon follow the classical period when only a male nude was an object of beauty? Was Song of Solomon perhaps written by a woman? Certainly, the main voice is that of a woman, and women were responsible for so much of song, celebration and lament, in Hebrew culture.

Motherly Joseph, Motherly God

When she’s a mother, even a mother in question, then readers and Bible translators have little trouble having her act motherly.

For example, in the biblical story of the man, King Solomon, and of that wisdom of his, there are women who are unnamed and unknown and whose character is called into question. What I hope we can all see is how the womb of an unnamed woman functions, in a literary way, to highlight the man and the brilliance of the man.

And so we may also be able to see how the male NET Bible translator also brings forth his translation, relying on the woman to mark what serves the decision of the man. Here comes 1 Kings 3:26a for the New English Translation Bible:

The real mother spoke up to the king, for her motherly instincts were aroused. She said, “My master, give her [the other mother] the living child! Whatever you do, don’t kill him [the male child]!”

Such arousal of motherly instincts even comes across and through the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, that “Old Greek” version of the Septuagint (which is also known as ΒΑΣΙΛΕΙΩΝ Γ or 3 REIGNS 3:26a). So then born out of that Hebraic Hellene comes the NETS (or New English Translation of the Septuagint) rendering by Bernard A. Taylor:

And the woman whose was the living son answered and said to the king —- because her womb was troubled over her son —- and she said, “With regard to me, my lord, give her the boy, and by death do not put him to death,”

The original Hebrew phrase in question is נכמרו רחמיה /racham kamar /, and its Greek phrase counterpart here is ἐταράχθη ἡ μήτρα αὐτῆς / eTaraCHTHē hē Mḗtra Autēs /. In the English of the NET Bible and of the NETS translation this means something exactly like these noun phrases: “her aroused motherly instincts” and “her troubled womb.”

When we read the Hebrew text carefully, and if we notice the Hebraic Greek translation as well, then we understand how the “womb” here functions rhetorically for (male) readers. It’s the device that gives the Judge, the King, the Man, his insight. The unknown woman is there to give birth to this wisdom of his. She, of course, needs not be a protagonist in the story. And her reputation is only at stake when compared with another woman whose reputation is worse. These women are there in the story for the Kingly Judge (and for the readers themselves) to judge. Then at one point in the narrative, there is that something that’s telling, the revelation of the something that’s “motherly,” the demonstration and protestation of the aroused “womb.” Out of this motherliness marked in the text is birthed the male Monarch’s wisdom. Solomon is a wise man, the wisest man in all the land.

When we shift our reading back to the Torah (to the first of the Five Books of Moses), and when we fast forward to the Prophet (to the Book of Isaiah), then we see something similar.

There, however, both in Genesis 43 and in Isaiah 63 we find something quite different. The Hebrew demonstrates this. And some translations do too. This is where the man Joseph is the protagonist (in Genesis) where God is in the dock, is on the stand in the court of judgment (in Isaiah). The problem is that there is no explicit woman in either context. Hence Joseph and the LORD become surrogate mothers in a literary and a rhetorical sense.

Reader’s and translators alike tend miss how motherly the man Joseph and the LORD Himself are in the Hebrew.

Just by way of illustration, the NET Bible translator himself has the following respectively for Genesis 43:30 and Isaiah 63:15 –

Joseph hurried out, for he was overcome by affection for his brother and was at the point of tears. So he went to his room and wept there.

and

Look down from heaven and take notice,

from your holy, majestic palace!

Where are your zeal and power?

Do not hold back your tender compassion!

To be sure, the NET Bible translator does see something in Genesis akin to what he saw in 1 Kings. Thus, he offers his readers his footnote on the Genesis verse, saying:

Heb “for his affection boiled up concerning his brother.” The same expression is used in 1 Kgs 3:26 for the mother’s feelings for her endangered child.

“The same expression” for the NETS Bible translator must be, nonetheless, translated differently. For Joseph is a King, a Man, the Judge, in this context.

Joseph is not the unnamed mother being judged. Or isn’t he? Readers of the Bible can judge just how motherly the Hebrew language of the Torah makes him here. The verse before describes Joseph this way (as translated in the King James Version) –

And he lifted up his eyes, and saw his brother Benjamin, his mother’s son, and said, Is this your younger brother, of whom ye spake unto me? And he said, God be gracious unto thee, my son.

The eyes of readers, even readers of this old English, are directed to the fact that Benjamin is described not as Rachel’s son but as his “mother’s son” (where the possessive pronoun his ambiguously refers to either brother); and we all can see how Joseph calls Benjamin, “my son.” A new ambiguity is introduced. The man Joseph is assuming the position of a parent, perhaps a father; and perhaps more implied is that Joseph is serving as mother.

Indeed the Hebrew of the very next verse, Gn 43:30, uses the same expression for Joseph as it does for the unnamed mother in 1 Kgs 3:26. The very response of Joseph at seeing “my son,” this “mother’s son,” is certainly a motherly response generated by profoundly aroused motherly instincts. (The Greek used by the Septuagint translator[s] is also the same for both 1 Kgs 3:26 and Gn 43:30. The NETS translation of Genesis [by Robert J. V. Hiebert] can only, nonetheless, manage just to hint at something like the labor of childbirth by making the Hebrew-to-Greek-to-English rendering the following: “And Ioseph was troubled, for his insides were twisting up over his brother, and he was seeking to weep. And going into the chamber he wept there.”)

Now to the Prophet. The Hebrew used about Joseph in Genesis and for the unnamed mother in 1 Kings is also the Hebrew used in Isaiah 63 for the LORD. Craig Smith’s The Inclusive Bible is the only translation that I have found that picks up on the motherliness of God in this rhetorical context of Isaiah 63:15 –

Now look down from heaven,

and see us from your holy and glorious dwelling place!

Where is your zeal, your strength,

your burning love and motherly compassion?

Why do you hold them back from us?

Compare this with what the NET Bible translator himself has –

Look down from heaven and take notice,

from your holy, majestic palace!

Where are your zeal and power?

Do not hold back your tender compassion!

And note how the Greek Isaiah translation has τὸ πλῆθος τοῦ ἐλέους σου (for which the NETS translator Moisés Silva has “of your compassions“).

At the very least, the Hebrew context of Isaiah shows G-d as a Parent. With the use of the same phrase as for the mother in the Solomon story and for Joseph in the story of his laboring physically over his “son,” the rhetorical question of the Prophet is as if a son’s question to a Mother, or at least to a Motherly God.

Invisible Women

I picked up Invisible Women by Jane Fortune in Florence last week and set out to view some of the works by approximately 100 women painters displayed in Florence. Of course, I really wanted to see this picture by Artemesia Gentileschi so I made sure to visit the Caravaggio room in the Uffizi Gallery. Only to find out that the painting is currently in Chicago.

In1971, Linda Nochlin wrote an article titled “Why Have there been no Great Women Artists?” She stated,

The fact of the matter is that there have been no supremely great women artists, as far as we know, although there have been many interesting and very good ones who remain insufficiently investigated or appreciated; nor have there been any great Lithuanian jazz pianists, nor Eskimo tennis players, no matter how much we might wish there had been.

And concluded,

The question “Why have there been no great women artists?” has led us to the conclusion, so far, that art is not a free, autonomous activity of a super-endowed individual, “Influenced” by previous artists, and, more vaguely and superficially, by “social forces,” but rather, that the total situation of art making, both in terms of the development of the art maker and in the nature and quality of the work of art itself, occur in a social situation, are integral elements of this social structure, and are mediated and determined by specific and definable social institutions, be they art academies, systems of patronage, mythologies of the divine creator, artist as he-man or social outcast.

I think Jane Fortune and others have proven that Nochlin’s question was poorly worded. It should rather be “Why are we not equally aware of the great women artists as we are of the men?”

Fortune”s book Invisible Women cites over and over, commentary and evaluation by great contemporary artists that many women artists were accepted as equally great in their time. It is history that has betrayed us. Gentileschi had a successful career, not without difficulties due to her poor background and tumultuous adolescence filled with scandal, but was considered to be one of the more innovative and influential artists of the Renaissance, not just among women artists but among all Renaissance artists, both men and women. She was the first to portray women of the Hebrew Bible as strong and active, with righteous anger and agency, as protagonists equal to men.

Why are Artemesia Gentileschi and other women artists not better known? The answer, I think, stands in the Galleria dell’ Academia – the naked David. This is the dominant work of art in Florence. There is an art hierarchy and the naked male statue is at the top. Male beauty is the dominant value. General sculpture comes next, then paintings of biblical and pagan heroes, often nude or semi-nude, and then portraiture and still life. Women were excluded from dissecting cadavers, and from life drawing classes, which all involved male nudes. Men could sculpt, draw and portray nude men and women, but women could not. Many women artists excelled at portraiture, introducing new ways of portraying the family, women and the very young. But they were excluded from certain areas of art which have dominated historically. I personally can’t say why David and naked male beauty had dominated, but the architecture of Florence demonstrates that it has. I went on quickly to see Botticelli’s Venus, myself.

I believe that Gentileschi’s interpretation of women as protagonists made her art equal to men. But history was unwilling to recognize this as on par with men as protagonists. Not her fault. But this is why women need to engage in biblical studies. Men will not do justice to women on their own. Just won’t happen.

This is all just food for thought. If we didn’t have women artists, then the agency of biblical women would not be fairly portrayed in art form. If we have only male artists, then male bodies dominate. This demonstrates that self worship, not adoration of the opposite sex, is dominant. Gentileschi used herself as model for many of her paintings. Why not? Women need to portray women, and strongly, as she did. Chicago, here I come!

Prayers to She Who Is

Prayers to She Who Is by William Cleary

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I took this out of the Interfaith Library the other day and leafed through it. It’s based on the work and words of Sr. Dr. Elizabeth Johnson, whose book She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse I read for my trinity course a few years ago. Sr. Dr. Johnson’s work is thoroughly grounded in both scripture and tradition, from which she retrieves and emphasizes the feminine imagery for God that has always been there.

The prayers tend towards the verbose and clunky to my ear, a bit reminiscent of the Blue Mountain Arts card style of poetry. But there are some beautiful images, and a broad array of themes strongly clustered around care for the poor, the oppressed, and the earth.

I did particularly like the versicle at the end of each prayer, which in line one, addressed God by a name from the prayer followed by three descriptive gerunds ending in freeing, and line two was always In you we live and move and have our being.

The line-drawing illustrations are a worthy complement to the prayers. I particularly liked the image of ruach, She-who-is blowing creation into being, and the image of God as a woman pouring out a jar of water onto the soil to sustain the growing grain.

(Crossposted from Gaudete Theology)

“Dear Woman” – Odd Gospel Greek

λέγει ἡ μήτηρ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ πρὸς αὐτόν…

καὶ λέγει αὐτῇ ὁ Ἰησοῦς,

τί ἐμοὶ καὶ σοί,

γύναι;the mother of Jesus said to him…

And Jesus said to her,

“Woman,

what does this have to do with me?”

– John 2 (ESV)Ἰησοῦς οὖν ἰδὼν τὴν μητέρα καὶ τὸν μαθητὴν παρεστῶτα ὃν ἠγάπα

λέγει τῇ μητρί·

γύναι, ἴδε ὁ υἱός σου·

εἶτα λέγει τῷ μαθητῇ·

ἴδε ἡ μήτηρ σου.When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby,

he said to his mother,

“Woman, behold, your son!”

Then he said to the disciple,

“Behold, your mother!”

– John 19 (ESV)

If Mark’s gospel Greek has Jesus crying Αββα ὁ πατήρ, the odd gospel of John has its Jesus saying some odd Greek indeed.

The Greek word John’s Jesus uses when talking to his mother is not that very distant formal Greek phrase ἡ μήτηρ /hē mḗtēr/. Nor is it that childish childlike and girlish little girl Greek, that overly familiar term of endearment like μάμμη /mamma/ or the unambiguous μαμμία, μαμμία, μαμμία /mammia mammia mammia/.

No, those would have English equivalents respectively to phrases like these:

- what author P. D. Eastman wrote “To My Mother,” when he wrote his book for children entitled Are You My Mother, which happens to be incidentally one of the first books I ever read with my mother.

- what songwriter Freddy Mercury sang to his Mama (i.e., “Mama, I killed a man“), after he “did a bit of research” to write this, to sing further (i.e., “Oh mama Mia mama Mia Mama Mia”), which seems pretty clearly obviously to be what prompted:

- what songwriter Tommy Shaw wrote (i.e., “Oh Mama, I’m in fear for my life…”).

In Greek, never mind these English translations, the phrase μάμμη would be one where the writer of 4 Maccabbees is mixing up mother/woman/grandmother familial familiar Greek phrases (in chapter 16) and Paul would use it later when making clear to young Timothy that he keeps distinct his Mammy Lois from his Mother Eunice (in 2 Timothy, chapter 1). And the phrase μαμμία, μαμμία, μαμμία is what the little baby of Myrrhini is made to cry out by the nasty Cinesias in the play of Lysistrata by Aristophanes (lines 877 to 890, where the words for Mother, Mama, Mommy, Mommy, Mommy, and γυναιξί [gynaizi] get all mixed up).

Γύναι /Gynai/, of course, is what Jesus in the odd gospel Greek twice calls Mary, or Mariam, his mother.

Γύναι /Gynai/, of course, is what Jesus in the odd gospel Greek calls the unnamed loose wo-man of the outcast mixed-breeds of Samaria (in chapter 4).

Γύναι /Gynai/, of course, is what Jesus in the odd gospel Greek calls the unnamed wo-man caught in the act of having sex with another man’s husband (in chapter 8).

Γύναι /Gynai/, of course, is what Jesus in the odd gospel Greek twice calls an-Other Mary, or Mariam, who for all of her womanly public uncontrolled emotion fails to recognize him (in chapter 20).

It’s a far cry from crying Αββα ὁ πατήρ. So what are we to make of this odd gospel Greek?

The real, medical version of Goliath

How does Malcolm Gladwell write of Goliath? And David for that matter?

How are we to read it? The Bible Goliath and his?

First this (on the Bible Abraham) –

Above all we must keep in mind that narrative is a form of representation. Abraham in Genesis is not a real person any more than the painting of an apple is real fruit.

—Adele Berlin

Now this –

It’s telling that of all the biblical verses Gladwell cites, he avoids the one that provides the key to the non-medical readings of the story: “I come against you in the name of the Lord of Hosts.” This theological explanation for David’s victory may not be accurate; it may have been a matter of fast against slow, nimble against encumbered, innovative against conservative, as Gladwell suggests. But disabling Goliath — and thereby rendering God unnecessary and impotent — is an anachronistic imposition on the ancient text. It produces a creative reading of the story, but it fails to give us what Gladwell claims to be providing: an objective, timeless key to understanding Goliath’s defeat.

Reading the text in Gladwell’s way is a form of “now-ism”: It assumes that we understand the data better than those who are actually providing it for us. It is, unfortunately, symptomatic of numerous medical readings of the Bible. Many characters have been paraded through the amateur physician’s consulting room. King Saul wasn’t afflicted by an evil spirit from God, he was bipolar; the prophet Ezekiel’s terrifying visions were not messages from God, but the result of paranoid schizophrenia; and Job’s painful boils were no divine punishment but merely hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome, commonly known as “Job’s disease.”

The attempt to diagnose historical and literary figures using modern medicine obscures the fact that the significance of their physical characteristics has to be evaluated in context. The overconfident giant to be slain here is surely the short-sighted arrogance of modern diagnostics.

– Joel Baden

Frankenstein Changes

Over the past few days, and hours, there’s come news about the manuscripts of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein being digitized. See the Washington Post’s It’s alive — and digital!; the New York Times’ ‘Frankenstein’ Manuscript Comes Alive in Online Shelley Archive; the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Frankenstein’s Manuscript Draws Its First Breath Online; and The Shelly-Godwin Archive’s very own home-page announcement:

Please note that this is a temporary site that will only be active until we officially go live at 8:00 pm on Thursday, October 31st. Please visit us again after that time.

If you’re here and can’t wait the few more hours, then there is one preview image up already on this page: http://shelleygodwinarchive.org/images/Dep.c.534.1-92r.png.

I thought it interesting to see what Frankenstein changes Mary Shelley, or her editor(s), made from this handwritten manuscript to the January 1, 1869 print edition. The latter can be found in google books / google play, in the Project Gutenburg, and via amazon.com for the Kindle. I’ve highlighted the changes in the texts from hand to print, below. What do you make of them?

She and He may be Abba

This is a “so what” post. I really like the comment of my co-blogger, Craig, saying, “I have always found this whole discussion irritating. Our words for our parents obviously come from infancy.” It is irritating, to me too. (This is a third, and final, post in a series; here are part one and two.)

Let me confess why, for me, there really is a “so what” that makes be want to engage in the discussion. It much has to do with how my parents submitted themselves to a certain “biblical parenthood” that had him as the alpha-male dominant Pater (as in Patriarchy, Head of Household, Spiritual Leader) and her as the submitter, with God, even the Trinitarian Christian God as the exemplary, the model, for this hierarchical arrangement. (I think it was Wayne Grudem’s continued publications of how he reads Paul’s letter to the Galatians that prompted my series of blogposts here, btw.)

To begin to do this confession of the why-this-irritating discussion of God-as-FATHER may be important, let me have us look at the MT and the LXX and certain Englishings of the Bible and how the Book represents certain ones by the sounds “Ab” and “Abba.”

Let’s look, for example, at Isaiah 9:6. At Christmastime we hear it in Handel’s Messiah sung:

And His name shall be call-ed,

Wonderful,

Counselor,

The Mighty God,

The Everlasting Father,

The Prince of Peace

We hear, the “child,” the “son,” … shall be called … Father.”

To hear this in the Jewish Publication Society’s English is to hear that this way:

“For a child is born unto us, a son is given unto us; and the government is upon his shoulder; and his name is called Pele-joez-el-gibbor-Abi-ad-sar-shalom.”

For this same Hebrew אֲבִי-עַד, Craig Smith in The Inclusive Bible, has “Eternal Protector,” with the footnote that says the Hebrew is “Literally ‘parent forever,’ though the context emphasizes a parent’s protective role.”

The Hebraic Hellene version of this, aka “the Greek Isaiah” that Abram K-J blogger has had several of us reading together this year, has the following “translation”:

So what?

Well, the “biblical” name for this Child, this Son, prophesied as G-d in part sounds like אב. These are sounds children, even boys, have made for their parents throughout human history. The adult meanings attached extend from this intimacy, from this literality, in ways that the adult Father Walter Ong theorized from orality to literacy, as if one is primary and the other much more adult-like.

When adults, scholars, authorities like pastors, and Fathers, and complementarian “head” husbands interpret, they tend to do like Aristotle did. They tend to avoid ambiguities and to teach others to do so if they’re to use language properly and not improperly. They tend to separate the terms, one from another. They tend to divide meanings so that the one in the binary is absolutely not the other. And they tend to put the one as over and in opposition to the other. This is their “terministic screen” to borrow a term from the rhetorician Kenneth Burke.

After my days of atheism (in the household of my parents, who were Southern Baptist complementarian Trinitarian Christian missionaries), I found myself unable easily to refer to (much less to pray to) God as “Father” when the “Bible” so clearly endorsed sexism. In our home, we not only had to tolerate such but we fundamentally saw it as Natural, as the way of God and His Nature, as spoken in his adult Word, where children, and women, had no voice.

As an adult, I’m amused now by the whole discussion (or debate) over Abba. I’m irritated that the adults who taught me the Bible as a child didn’t show Isaiah’s images of God as Father as so different from human fathers, like my own (by reading, say, Isaiah 63:16 and Isaiah 64:8, which respectively have those Hellene translations of sú kúrie patḕr and kúrie patḕr hēmȭn [σύ κύριε πατὴρ and κύριε πατὴρ ἡμῶν]). And now when I find curious items in the Septuagint, like a mother being named Αββα, then I just blog about it; whatever the reason for that “translation” or slip of the tongue or the pen of an editor, it sure sounds like language play, which children and adults engage in with all of their meanings, some intimate like an inside joke. Language, or more precisely, all the ways we humans use our language, is a lot more robust than we often want to give ourselves credit for. The power for some in using language is their ability to contain Reality somehow by it, and even Language or languages or Αββα as Natural and self-evident. That’s hardly all that language is, nonetheless.

I am grateful for the blogging community, especially my cobloggers here, and for Craig’s work in Bible translation and his comment here. (Do read his Bible, and notice how he uses Abba throughout!). I appreciate James McGrath’s conversation and James Pate’s reblog. I also want to say a Thank You to Abram K-J blogger not only for his organizing the reading of Greek Isaiah but also for his ongoing Septuagint Studies Soirée, now with the third installment here.

Pater may be Daddy

Each of the three occurrences of αββα in the NT is followed by the Greek translation ο πατερ, “the father.” This translation makes clear its meaning to the writers; the form is a literal translation — “father” plus a definite article — and like abba can also be a vocative. But it is not a diminutive of “babytalk” form. There are Greek diminutives of father (e.g., παππας [pappas]), and the community chose not to use them.

– Mary Rose D’AngeloThe Greek word used in the New Testament is always the normal adult word πατήρ [pater] and never a diminutive or a word particularly belonging to the speech of children.

– James BarrBarr rightly points out that in contrast to Aramaic or Hebrew “words somewhat similar in nuance and usage to our ‘Daddy’ did exist in Greek….” This does not show, however that abba was fully equivalent to the Greek ‘father’; since in Aramaic abba was not in contrast to another word [meaning ‘daddy’] and [in Greek] pater was, their value was necessarily different.

– Anna WierzbickaThe following statement in the Talmud was often used to support this view [that Abba may be Daddy]:

An infant cannot say “father” (abba) and “mother” (imma) until it has tasted of wheat [i.e., until it is weaned]. (b. Ber. 40a; b. Sanh. 70b; Tg. Isa. 8:4.)

…. While it is true that children would address their father as abba, it is also true that grown children would address their father as abba…. It is true that little children called their father abba, but these were the normal words of the language and they were “correct and grammatical adult Aramaic.” The early church and the writers of the NT demonstrate this understanding of the term in that they do not translate abba as “Daddy” but as “Father.” If they thought it meant “Daddy,” they could easily have revealed this by translating the term by the diminutive term patridion (“Daddy”). They never did this, however. They instead used patēr (“Father”). Thus it is best to understand abba as a reference by young or old to their “Father.”

– Robert H. Stein

This blogpost starts in by quoting the Mamas and the Papas of “Exactly How the N-T and the Early-Church Writers Literally Translate Abba into Greek as Meaning Only ‘Father’ (and NOT at all as daddy).”

Well, that’s not true is it?

To be sure, I have not quoted Moms and Dads but have used for my epigraphs for this blogpost only exact quotations by the literal mothers and the literal fathers of the semantics of the Aramaic phrase אבא and its Greek equivalent αββα. Ha ha, you my dear readers may respond. And, yes, I’m attempting to be funny. It is humorous how we can play with our language(s). It’s laughable to say that someone, or even something [like the semantics of a phrase], has more than one mother and more than one father, since, as we all know it literally takes one and only one father and one and only one mother to have babies. Ha ha, again.

But, of course, we’re now even using “literal” in a metaphorical sense.

And at no point so far in this post has our English really ever pointed to a literal, or shall we say a “biological,” mother or father.

This is some the point.

We get all hung up on what αββα in the Greek gospel of Mark isn’t. “Abba isn’t Daddy,” we say and we hear over and over. It is really only just simply merely Father, like adults would use for their address to their fathers. “Jesus really said αββα,” we hear the scholars declare. It’s clearly obviously indisputably in what Wierzbicka agrees is one of “the sayings widely regarded by reputable scholars as preserving Jesus’ ipsissima vox and ipsissima verba.” To put that in the words of some of those scholars, “If Jesus could not speak Greek, we [Members of the Jesus Seminar] must conclude that his exact words have been lost forever, with the exception of terms like ‘Abba,’ the Aramaic term for ‘Father,’ which Jesus used to address God…. The Fellows agreed that Jesus used the term ‘Abba’ (Aramaic for ‘Father’) to address God. To this term they gave a rare red designation.” The scholars writing using the English alphabet (for ‘Abba’) reading the gospel writer using the Greek alphabet (for αββα) all use the Greek appositive, or “translation,” ὁ πατήρ, to say what Jesus really meant. And Paul too. His extant letters, full of fragments though they might be, copyist revisions and the like, nonetheless maintain not one but two “Αββα, ὁ πατήρ” – s. This is a lot of scholarly weight. Especially when the scholars know exactly how the Greek works. Know the Greek, know the Aramaic that the Greek surely translates. It’s “Father.” “Abba isn’t Daddy.” Since Father, in Greek, isn’t Daddy. We know “babytalk” form; and this ain’t that. Wierzbicka, whose book What Did Jesus Mean?, explicates “The meaning and significance of the word abba,” says definitively that “it certainly did not mean ‘daddy’ and — unlike pápa [in French], papá [in Russian], babbo [in Italian], and tato [in Polish] — was not specifically a children’s word…. Barr rightly points out that in contrast to Aramaic or Hebrew ‘words somewhat similar in nuance and usage to our “Daddy” [in English] did exist in Greek….’ This does not show, however that abba was fully equivalent to the Greek ‘father’; since in Aramaic abba was not in contrast to another word [meaning ‘daddy’] and [in Greek] pater was, their value was necessarily different.” Paul didn’t write Αββα ὦ πατρίδιον to his pals in Rome. Paul didn’t use Αββα ὦ παππία with his intimate buddies in Galatia. Mark’s Greek gospel fails to quote Jesus ipsissima vox or ipsissima verba as saying Αββα πάππαν. And therefore, case closed: “Abba isn’t Daddy.” Are we hung up on this yet?

Yes, and yet. Two problems with getting so hung up on this.

One:

“father” and “père” and “otéc” and “padre” and “ojciec” do not necessarily and always indicate some strictly-spoken more-formal-than-baby-talk adult-talk for the male parent. The range of meanings of the Hebrew phrase אב, especially for G-d in the Bible, is vast. And to use this language is sort of anthropomorphic. It’s definitely a word that applies, in human terms, to animals and humans, to creatures created (or species evolved) and that are sexual and that are spawning offspring. How is it a name for the Creator? How is it a description of Deity? As soon as it’s applied to “him,” then it is no longer “literal.” And so if Jesus is calling God “Father,” and if Paul is writing only “Father” when using “Abba” for God, then already the meaning has shifted from the literal meaning of “father.” The use of such a term, in any language, is never literal when applied to God. It is always metaphorical. And translational.

Which brings us to Two.

Two:

the Greek terms for father/daddy that the Bible scholars I’ve quoted here say are always and only different terms (adult-talk / baby-talk) may indeed be variants of the same term.

Little Greek children did indeed say ὁ πατὴρ as their “babytalk.” And adults, acting like babies, called their dads by these variants:

ὁ πατὴρ

ὦ πάτερ ὦ πάτερ

ὦ πάτερ

πάππαν

ὦ παππία

ὦ πάτερ πάτερ

ὦ πατρίδιον

And the “early church,” despite what Stein would insist, did see themselves as approaching God as little children.

Clement of Alexandria, for example, writes in his Protrepticus:

Ἡ δὲ ἐκ πολλῶν ἕνωσις ἐκ πολυφωνίας καὶ διασπορᾶς ἁρμονίαν λαβοῦσα θεϊκὴν μία γίνεται συμφωνία, ἑνὶ χορηγῷ καὶ διδασκάλῳ τῷ λόγῳ ἑπομένη, ἐπ’ αὐτὴν τὴν ἀλήθειαν ἀναπαυομένη, «Ἀββᾶ» λέγουσα «ὁ πατήρ»· ταύτην ὁ θεὸς τὴν φωνὴν τὴν ἀληθινὴν ἀσπάζεται παρὰ τῶν αὑτοῦ παίδων πρώτην καρπούμενος.

The union of many in one, issuing in the production of divine harmony out of a medley of sounds and division, becomes one symphony following one choir-leader and teacher, the Word, reaching and resting in the same truth, and crying Abba, Father. This, the true utterance of His children, God accepts with gracious welcome-the first-fruits He receives from them.

Pater may indeed be Daddy. And if so then what might Abba be?

Female Hysteria and Harm in Saudi Arabia

It’s already started! Just as predicted:

Last month Sheikh Salah al-Luhaydan, a well-known cleric who also practises psychology, claimed on a popular Saudi website that it has been scientifically proved that driving “affects the ovaries” and leads to clinical disorders in the children of women who are foolish enough to drive.

Yes, and Aristotle proved long ago in his History of Animals (493a):

Του δε θήλεος Ιδιον μερος ύστερα, καί του αρρενος αίδοιον [The respective part of a female is an emptiness, ovaries, utter hysteria, a uterus, and so different from that of the sane point of a male, a spear, a penis.]

This is the earliest report today so far I’ve seen, from USA. Watch at your own peril.