This post is another in a series on the interpretive spins and literary sparks in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Tehillim called Ψαλμοὶ (or Psalms). Translating the Septuagint (LXX) Greek into English, Albert Pietersma has noted that there are the sparks and spins, but he fails to identify them. Pietersma in the NET Septuagint has said, for example, the following about the translator of the Hebrew into the Greek:

and

My eye was directed to a possible literary spark in Psalm 68 this past week. Wayne Leman posted an announcement about the new “International Standard Version” of the Bible, and I was looking at how Dr. Mona Bias (for the ISV) had translated the Psalm. Although the ISV editors generally seem to suggest that their English is to be English as an international language, I was wondering.

Also, the ISV translators supposedly use the LXX Greek among various resources. So here is what I noticed, when comparing what Bias has done for the ISV with what other version translators have done (who don’t necessarily use the LXX as a source and who do often translate with English regionalisms). I’m just comparing the very first part of verse 14 (or 13, depending on the numbering system):

Now here is how Robert Alter translates the same (and as we all know Alter refers to the LXX many times):

In this case, however, it seems that Alter finds nothing useful in the Greek rendering of the Hebrew. His note points to other issues:

We can compare Alter’s translation with Bias’s. And we can add to these Ann Nyland’s rendering of the same. The reason Nyland’s might be interesting is that she, like Bias and like Alter, also consults the LXX. Nyland has this:

Her footnote gives these explanations:

Now, let’s compare the Hellene of the LXX with the Hebrew. The Masoretic Text has this:

The LXX translator has this:

Pietersma makes this Greek the following English:

And Brenton’s English version of that Greek goes like this:

So what’s going on?

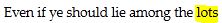

Could it be that there’s an allusion to the lots so famously in Sophocles somehow? Like this:

commonly put into English like this?

Well, you can see that we have questions. On just this little bit of scripture, we have that much. We know we don’t know much. Except there is some fancy Greek before and after this little “lot.” The lot, of course, is an unusual bit to show up here in the Psalm. I think it’s an echo to the playwright for some now unknown reason. Maybe we’ll say more some later.

What do you think?

“Just don’t call them children.”

That’s the final sentence, the last paragraph, the final conclusion of L.A. Times reporter Michael McGough in his recent op-ed piece, “Was Trayvon Martin a ‘child’ or a ‘youth’?”

To be sure, McGough would not consider himself a child. He doesn’t want anyone calling the late Trayvon Martin a child either. And he gets into this broader discussion about (English) words for children. Which makes me wonder, again, how he can police language so. In Greek and Hebrew, in some of the biblical languages, there is more freedom, more poetry, more narrative metaphor, than McGough would allow us.

In the gospel of Mark, for example, there’s this use of the term paideia (or παιδεία) around which Werner Jaeger wrote three volumes. (This is in English translation by Gilbert Highet.) Here, for the one term, there’s a range of meanings, a range of ages, from infancy through the teen years into the 20s even. Yesterday, I blogged elsewhere a bit about how Mark’s gospel portrays Jesus as being indignant at adults who fail to recognize the value of παιδία. That’s Mark 10:13-14, but the writer of the gospel of John (Jn. 21:5) even has Jesus calling these same adults παιδία.

This gets us recalling the Septuagint (Greek translation of) Genesis, and the story of Jacob and his twelve sons. In Genesis 43:8, Judah is appealing to his father Israel, saying, “Send the child, the youth, the teenager, with me.” The Greek phrase is παιδάριον. This is for the Hebrew word with a very similar range of meanings and age: נער. Later in the text, the Hellene translation adds some wordplay that actually exploits the ambiguities of the Greek word. It also can mean “youth in training” and even “servant apprentice” and even sometimes “slave.” So the Greek text in Genesis 43:18 has the older brothers suggesting that Joseph treat them as child–slaves in Egypt (a sort of literary foreshadowing of the events of the second of the five books of Moses): ἡμᾶς εἰς παῖδας (for לעבדים). And then in Genesis 43:28, there an alliterative wordplay, an appositive, suggesting that “your child-servant” is “our father”: ὁ παῖς σου ὁ πατὴρ ἡμῶν (for לעבדך לאבינו).

I’m trying to suggest that policing language, that disallowing phrases like “child” and “children” for 17 year olds, is ironically the very sort of manipulation of language that McGough is accusing others of doing. Whether our present languages or the ones of the ancients, the terms for children can be intentionally very expansive.

Before we were co-blogging here, Theophrastus and I discussed at one of my blogs what he called the “classic missionary focus” of Bible translation. Today, blogger Rod at the blog Political Jesus has posted something along those lines with his brother Richard. They investigate some of the missionary focus of translation of the Bible in the history of colonial contexts. Here are just a few lines (from Richard, on this history, then from Rod, on the present and continuing implications):

The effects of imperial powers extend far beyond the immediate period of colonization. This truth is most evident when exploring the relationship between colonization and biblical hermeneutics [as manifest in translation]. The British and Foreign Bible Society diffusion of scriptural imperialism in India mirrored the efforts of the slaveholders in America to appropriate the bible for slaves…. The British and Foreign Bible Society monopolized the translation of the biblical text for the Hindu people. They used their English language as the basis for all translation…. One translator noted the lack of Christian vocabulary present in indigenous cultures by stating: “Not only the heathen, but the speech of the heathen must be Christianized. Their language itself needs to be born again.”… The American slaveholders were firm in their belief of the African slave’s inability to comprehend the entire message of the biblical revelation. This stance mirrored the British and Foreign Bible Society’s view of the native people in India. Inculcating Christian doctrines upon the African slaves was reinforced through the use of textualization.

English bible translations, do in fact, begin on the backs of the colonized, and continues… Whenever you hear or read of a bible translation for/by women or People of Color as being “contextual” or “special interest,” the colonizing gaze of biblical studies rears its head. European colonialism is a special interest. White supremacy is a special interest. Male domination is a special interest. English-onlyism is a special interest. Bourgeois values, with the politics of respectability and white hegemonic liberalism, are special interests.

The full post is here: India, English Bibles, British Empire, And the Foreign Bible Society: A Joint Post

Heart, Memoir, Book, Memoir, Private Matters

I’m reading three books at once, which is impossible. Or should I maybe more correctly say that the three books that I’m reading are impossible?

They are three books by two psychotherapists about their respective fathers. Their fathers are very famous writers, whose books of fiction I have much appreciated.The factual biographies about these famous writers are written, by their children, now after their respective deaths.

The biographers, respectively, are conflicted about much of what they have felt compelled to write, to publicize, about their fathers. You can imagine the heart issues, the book life, the private matters. These children, now professionals of the human soul, have an unusual role to play in their writing. How much analysis do they do, how much do they share?

In this blog post soon, you’ll read which books these are. They are well written and are elsewhere well reviewed. I’d recommend them to you. When I say they’re impossible, then I’m just being personal. I think the books are personal. I’ve come to these three books after my own father died. After finding his own notes in a book by a psychologist named Paul Tournier, I started reading books about psychotherapy by psychotherapists, Jung, Freud, Adler. (This some has to do with the fact that one of my own children is studying to be a psychologist, and her grandfather, my father, encouraged this some.) At any rate, these are private matters, no? Here is my own father’s handwriting in the Tournier book:

What I’m intrigued by is how many many people knew my father. And yet how few knew him as I did. So does one tell what one knows? Why? How? Where? For whom? For posterity? For the grandchildren?

These are some of the motives of Greg Bellow. He’s one of the biographers of one of these three books I’m reading. His is Saul Bellow’s Heart: A Son’s Memoir. His very title, with its subtitle, is fractured by the punctuation dividing the one from the other. The book itself starts at the funeral, at the son’s realization how there are others in Saul Bellow’s family (a literary family, nothing like Greg Bellow’s family growing up). The book itself is structured so as to tell of two fathers, two Saul Bellows.

The motives of Janna Malamud Smith were similar. She is the other of the biographers, the biographer of the other two books I am reading. Hers are Private Matters: In Defense of the Personal Life and My Father is a Book: A Memoir of Bernard Malamud. She inspired Greg Bellow perhaps. Her father and his father were friends and were both the famous writers of fiction, the very influential writers of books, that I mentioned at the start of this blogpost. She starts off a talk about their fathers, and their biographies, in a video online here.

I think these three books belong together in a way. I think they are in part the intersection of two families, two children, two professions, two sorts of writing, in books. I said reading these is impossible. And yet I’m quite sure if I don’t I will have missed much. Already the fathers have impacted me. And now I find more in common with these their two children. Private matters, heart, memoir, book, memoir, are now open, to be opened and read.

There are a number of things in China that are not spoken in public easily. Chinese speaker Julian Baird Gewirtz, writing for The Huffington Post, did manage to report publicly on his hearing and presumably speaking “a marvelous bilingual pun”:

“To bi or not to bi?”

Gerwitz was at a play written by a woman for English audiences, translated by a man for Chinese audiences. A part of the “crowd on opening night, which was predominantly women, [who] seemed highly excited,” some “college students,” with “[a]most everyone attending the performance … under 30,” he was “the only Caucasian person there.” Gerwitz goes on:

As in the English-language version, the actress Lin Han concluded one of her pieces by chanting the word “bi” over and over again, zealously calling on the largely female audience to do the same. But from this Beiing crowd, a few male voices yelled out the word once; not a single female voice could be heard…. As I talked to some Chinese young men and women after the show, they seemed undecided. “It was very challenging for me to hear that word [bi] said by a woman,” said one young woman. “Men use it, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard a woman say it before.”

For his English-reading Huffington Post audience, the reporter translates: “the word “bi” [is] a vulgar slang term for the female genitalia.” He goes on to report how, with no apologies either to Mr. William Shakespeare or to Ms. Eve Ensler, Mr. Wang Chong has radically played on Hamlet’s opener and has rendered The Vagina Monologues as simply The V Monologues or, officially, “‘V独白’ (V-dubai).” Here’s the fuller report of what took place on that March 11, 2009.

(Time magazine’s Emily Rauhala followed up also to recall that this really was not the first attempt in China to translate and to show the play; she suggests that it was the unspeakable word in question that, in 2004, led to failures of tries at official runs of the play for Chinese audiences. The Chinese entry on the play in Wikipedia gives some of the history and maintains a link to the Wang Chong online public announcement, which is a bilingual program.)

Another Chinese speaker, writing for The New York Times, has today reported on something similar. Didi Kirsten Tatlow has told of the play “Our Vaginas, Ourselves” which has shown since January 2013 “about 10 times in Beijing, Tianjin and Xiamen.” She explains how the “English title… makes reference to the feminist classic ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ — its Chinese title translates as ‘The Way of the Vagina’.” Tatlow quotes the play’s producer to summarize it:

Of the play’s 11 scenes, eight consist of original material, while two are Chinese translations of excerpts from Ms. Ensler’s “The Vagina Monologues,” and one is from an earlier Chinese play inspired by the American play, Ms. [Hang] Ji said.

And she describes the very opening scene:

“I’ll say it: vagina!” two actresses, called A and B, say in Mandarin, on a stage with minimal props.

“I’ll say it in the Shanxi dialect: vagina,” B says. “In the Wenzhou dialect: vagina,” A says.

Then it’s the Hubei dialect, and so on until they have uttered the word in 10 dialects, the audience reacting with delight to the shock of the familiar, yet rarely heard word, spoken in their hometown tongues.

Now, the NYT reporter is writing this for English reading audiences. Chinese readers would likely see this as 阴道! Quite a start to any play in any language!

(These reports, written by Chinese speakers for English readers, suggest that translations — and even the originals too — hardly get at all the play. There is “trans-cultural” and “bi-lingual” and [what Mikhail Epstein might call] “inter-lational” play here. There is feminist play that encroaches on the male domains, in both the West and in China. It some reminds me of an internet youtube version of A Chinese Girl’s Vagina Monologues Presentation In University. Some plays must be experienced, and read, and read, and heard. It’s all very complex, except for people like Didi Kirsten Tatlow and Julian Baird Gewirtz, who seem to live [what Pearl S. Buck called] mentally bi-focal. UPDATE: I meant to include this link to bilingual reporter Eric Abrahamsen‘s post, “The Unspeakable Bi,” as if that might help some readers here with what the audience of V独白 was struggling to say.)

A new language?

The New York Times is reporting that Carmel O’Shannessy has found a language in its formative period of creation in northern Australia. But I think its lead exaggerates O’Shannessy’s claims:

There are many dying languages in the world. But at least one has recently been born, created by children living in a remote village in northern Australia. Carmel O’Shannessy, a linguist at the University of Michigan, has been studying the young people’s speech for more than a decade and has concluded that they speak neither a dialect nor the mixture of languages called a creole, but a new language with unique grammatical rules. The language, called Warlpiri rampaku, or Light Warlpiri, is spoken only by people under 35 in Lajamanu, an isolated village of about 700 people in Australia’s Northern Territory. In all, about 350 people speak the language as their native tongue.

But O’Shannessy seems to claim less novelty in a recent abstract:

Light Warlpiri, a new Australian mixed language combining Warlpiri (Pama-Nyungan) with varieties of English and/or Kriol that has emerged within approximately the last thirty-five years, shows radical restructuring of the verbal auxiliary system, including modal categories that differ from those in the source languages. The structure of Light Warlpiri overall is that of a mixed language, in that most verbs and some verbal morphology are drawn from English and/or Kriol, and most nominal morphology is from Warlpiri. Nouns are drawn from both Warlpiri-lexicon and English-lexicon sources. The restructuring of the auxiliary system draws selectively on elements from Warlpiri and several varieties and styles of English and/or Kriol, combined in such a way as to produce novel constructions. It may be that when multiple sources provide input to a rapidly emerging new system, innovative categories are likely to appear.

As I understand her claims, O’Shannessy is asserting that most of Light Warlpiri draws from English, Kriol, and Warlpiri, with some novel constructions in the verbal auxiliary system. In particular, it is somewhat misleading for a newspaper to claim Light Warlpiri is “neither a dialect nor the mixture of languages called a creole” when the researcher involved asserts “the structure of Light Warlpiri overall is that of a mixed language.”

reading Aristotle’s poetry

Today for us there are at least two problems with reading Aristotle’s poetry. The first is that it’s poetry that is Greek. The second is that it is Aristotle’s. Let’s read anyway.

First let’s read what certain readers of Greek have written, have warned perhaps. Here’s Virginia Woolf from 1925 –

For it is vain and foolish to talk of knowing Greek, since in our ignorance we should be at the bottom of any class of schoolboys, since we do not know how the words sounded, or where precisely we ought to laugh, or how the actors acted, and between this foreign people and ourselves there is not only difference of race and tongue but a tremendous breach of tradition. All the more strange, then, is it that we should wish to know Greek, try to know Greek, feel for ever drawn back to Greek, and be for ever making up some notion of the meaning of Greek, though from what incongruous odds and ends, with what slight resemblance to the real meaning of Greek, who shall say?

It is obvious in the first place that Greek literature is the impersonal literature. Those few hundred years that separate John Paston from Plato, Norwich from Athens, make a chasm which the vast tide of European chatter can never succeed in crossing. When we read Chaucer, we are floated up to him insensibly on the current of our ancestors’ lives, and later, as records increase and memories lengthen, there is scarcely a figure which has not its nimbus of association, its life and letters, its wife and family, its house, its character, its happy or dismal catastrophe. But the Greeks remain in a fastness of their own. Fate has been kind there too. She has preserved them from vulgarity. Euripides was eaten by dogs; Aeschylus killed by a stone; Sappho leapt from a cliff. We know no more of them than that. We have their poetry, and that is all.

But that is not, and perhaps never can be, wholly true. Pick up any play by Sophocles, read–

Son of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon,

and at once the mind begins to fashion itself surroundings. It makes some background, even of the most provisional sort, for Sophocles; it imagines some village, in a remote part of the country, near the sea.

The problem of reading Greek writers is fairly discussed, and Woolf admits, “We have their poetry, and that is all.” But, she allows something more to get beyond the difficulties. At first glance, it seems that “any play by Sophocles” solves our problem. It opens our mind, she suggests, to our familiar. But that only returns us to the place we start: we have “our ignorance” and “we do not know.” The title of Woolf’s essay, of course, is “On Not Knowing Greek,” as in her book, The Common Reader.

Then there’s the related difficulty of getting to anything by Sophocles in the first place. I do get that we have good translations, and yet there is what the translators have had to do to get to the Greek. Here’s C. S. Lewis from 1942 –

An enjoyment of Greek poetry is certainly a proper, and not a mercenary, reward for learning Greek; but only those who have reached the stage of enjoying Greek poetry can tell from their own experience that this is so. The schoolboy beginning Greek grammar cannot look forward to his adult enjoyment of Sophocles as a lover looks forward to marriage or a general to victory. He has to begin by working for marks, or to escape punishment, or to please his parents, or, at best, in the hope of a future good which he cannot at present imagine or desire. His position, therefore, bears a certain resemblance to that of the mercenary; the reward he is going to get will, in actual fact, be a natural or proper reward, but he will not know that till he has got it. Of course, he gets it gradually; enjoyment creeps in upon the mere drudgery, and nobody could point to a day or an hour when the one ceased and the other began. But it is just insofar as he approaches the reward that he becomes able to desire it for its own sake; indeed, the power of so desiring it is itself a preliminary reward.

What Lewis is describing is from his own particular experience (as he relays that for general consideration to an audience in a sermon he preached, which we all can hear a bit of here as produced by somebody else some years later). The point is that reading Sophocles or Greek poetry in general may be difficult, especially at first, when one is initially attempting somehow to “know” it.

Now we come to Aristotle, the Greek teacher from whom so many of us have learned. How do we know? Can we? Have we? Isn’t that the sort of thing that Greek Philo-Soph-ers would struggle with themselves as Epi-Stem-o-Log-y? Our own contemporary philosopher, an epistemologist herself, C. Z. Elgin has said this about our “knowing” Aristotle:

Aristotle, of course, was not named “Aristotle”; the name he went by had a different pronunciation and a different spelling. So the claim that our use continues the chain that began with his being baptized “Aristotle” needs refinement. Then there is the worry that chains that originate in a single stipulation may later diverge. In that case a term has two different reference classes despite its link to a single introducing event…. Ambiguity occurs because correction… allows for alternative continuations of the causal chain…. Each continues the chain, but the two uses of the word… are not coextensive. Nor do we always succeed in referring to what our predecessors did, even when we intend to do so.

Elgin makes her observations about us in around 1997, in her wonderful book, Between the Absolute and the Arbitrary. She’s saying that we don’t even really use Greek (not the alpha-bet nor the sounds they represented) when we read of Aristotle and speak of him with one another. How can we understand, or know, his works? How his poetry?

Those who study Aristotle, and his works, don’t all agree. For example, there’s rhetorician, not philosopher, George A. Kennedy. We must know Aristotle, Kennedy claims, not as a philosopher, especially not as a platonic philosopher, but we must know Aristotle as a rhetorician. Oblige me a longer quotation of Kennedy. He is speaking as if he and Aristotle are the same, the Aristotle he knows and not the one the philosophers, the platonists, would know. In 1992, he argues:

Our friends the philosophers have begun to take more note of the Rhetoric in their study of Aristotle, not out of a willingness to approach philosophy as a rhetorical discourse but in apparent hopes of weaving material from the Rhetoric more tightly into the network of Aristotle’s philosophy. All too many students of Aristotle are, in their hearts, Platonists. I am not only content, but delighted, when Professor Farrell proclaims that I am not a Platonist. Not everyone has noticed. . .

But suppose Aristotle had, as Plato did, explored the philosophical issues of rhetoric and inserted some such discussion into the text [of the Rhetoric]. We can reconstruct, either in his language or in postmodern language, what he might have said about political and ethical functions of rhetoric. If he had done so, I would suggest, some of us at least would now be engaged in deconstructing his remarks along the lines of Derrida’s deconstruction of Plato’s Phaedrus. That is to say, we would be exploring the slippages between a logocentrist position that gives some fundamental moral meaning to rhetoric in society and what Aristotle actually does in the text [of the Rhetoric] as a whole. Virtually every category and strategy discussed can be used for opposed moral purposes, and the only criterion we are offered is the parenthetical remark that we should not seek to persuade what is “base.” It is perhaps not too much to say that the central problem with the Rhetoric for those who approach it philosophically is that it comes to us already “deconstructed,” filled with différance, supplements, and “traces.” Ethical meaning is constantly differed, and key terms such as topos constantly repeat themselves both as the same and as different. . . .

My suggestion to the philosophers. . . is that instead of reading the Rhetoric as a work of philosophy they should try reading Aristotle’s major treatises on other subjects as rhetorical constructs. They might, for example, begin to observe the system of imagery prevailing in the Nicomachean Ethics, which is filled with teleological, emotionally based metaphors. What appear on the surface to be rational arguments are at the most usually enthymemes, not syllogisms, and their persuasive quality is often derived from ethos and pathos. They should explore also the concept of audience in each of the treatises, seen for example in the patterns in which Aristotle shifts from use of the first person singular to the first person plural.

Kennedy is contending, against philosophers (perhaps “straw-man” philosophers), that he knows and that they should know Aristotle rhetorically, even when Aristotle is purporting to being philosophical, ethical, or logical. If we know Greek philosophy as rhetorical, then how would we know Aristotle’s poetry?

Now we might listen to Jeffrey Walker. He also is a rhetorician. And he has this to write, to contend, about Aristotle’s poetry:

Aristotle is perhaps no great shakes as a poet.

Walker is making this assertion, in 2000, as he himself has commented on and has translated a poem composed in Greek by Aristotle. This is in one of his finest books, Rhetoric and Poetics in Antiquity. There he says:

Aristotle is perhaps no great shakes as a poet, but the basic operation of his song is of a piece with what we have observed already in Alcaeus, Sappho, Pindar, and Solon. (And one should not forget that Aristotle was, in fact, admired in antiquity for his literary skill.) The art or technê that describes the principles of this song’s argumentation is clearly rhetoric, as Aristotle understands it, supplemented by the principles of versification, music, and song performance.

So to know Aristotle’s poem, we might do well, if Walker is right, to know others who wrote Greek and were influences, literary influences, not only on Aristotle but on his audience. His poetry is “art” and more, art as argument. More context is required. More Greek is needed to know what he is doing or at the very least perhaps is intending to do to his readers, perhaps even to us, to you also, and to me too, if we can really count ourselves as reading Aristotle’s poetry.

Let’s look at the letters at least.

And let’s recall how many now have known this poem in English translation. Already at this blog we’ve considered these. The rendering by Andrew L. Ford:

The translation by “-R”:

The same lines different by Christopher North:

Now, we might consider more in this very post. Are we reading Aristotle’s poetry really? We might also consider this one English version by J. A. Symonds:

And one Diogenes Laertios has that this way:

O Virtue, won by earnest strife,

And holding out the noblest prize

That ever gilded earthly life,

Or drew it on to seek the skies;

For thee what son of Greece would not

Deem it an enviable lot,

To live the life, to die the death

That fears no weary hour, shrinks from no fiery breath?

Such fruit hast thou of heavenly bloom,

A lure more rich than golden heap,

More tempting than the joys of home,

More bland than spell of soft-eyed sleep.

For thee Alcides, son of Jove,

And the twin boys of Leda strove,

With patient toil and sinewy might,

Thy glorious prize to grasp, to reach thy lofty height.

Achilles, Ajax, for thy love

Descended to the realms of night;

Atarneus’ King thy vision drove,

To quit for aye the glad sun-light,

Therefore, to memory’s daughters dear,

His deathless name, his pure career,

Live shrined in song, and link’d with awe,

The awe of Xenian Jove, and faithful friendship’s law.

Here is David A. Campbell, whose work became part of the Loeb Classical Library:

Here’s the rendering published by William D. Furley and Jan Maarten Bremer:

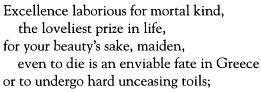

Finally, we come to Jeffrey Walker’s argument. Aristotle’s poem is rhetoric, an argument. In English, if we also could hear the other Greeks who come before this rhetorical poet, Aristotle might have his poem this way. Here is Walker’s rendering:

And now, problems and all, we might argue, we are reading Aristotle’s poetry of Excellence laborious for mortal kind.

The Zhuangqiao inscriptions

Various news media (such as this report) are reporting on a conference in Zhejiang province held on more than 200 objects at the Zhuangqiao archeological site dating back to Liangzhu culture. The objects are 5,000 years old.

Consider this stone implement:

Here are the inscriptions on the front

Here is a portion of the back of the same object

Here are the inscriptions on the back of the stone implement:

Or, consider the inscriptions on this stone axe:

Now remember up until now, the oldest evidence of Chinese writing that we have are oracle bones dating back to about 3,600 years ago. These artifacts, dating back a millennium and a half further, appear roughly contemporaneous with the oldest Sumerian cuneiform tablets that we have.

Now, admittedly, the complexity of the inscriptions does not approach the complexity of early cuneiform tablets. But it does suggest that Chinese writing may have started much earlier than we previously believed.

When Dickens met Dostoyevsky: postscript

We discussed the A. D. Harvey affair back in April.

Now the Guardian newspaper has an extended (and partly) profile on A. D. Harvey – it is currently on the front page of the US web edition of the Guardian.

AD Harvey doesn’t deny he is the creator of that community. Indeed, he says there are several identities which even Naiman has failed to unearth: [… including] a variety of internet personalities which he prefers not to disclose as he says they might not reflect well on his output and interests.

Comments are turned off for this post.

Robert Alter hits the book tour circuit

Robert Alter has been hitting the book tour circuit promoting his translation of the former prophets, Ancient Israel, which we noted here.

Here are some interviews:

And some reviews

Francis on Isaiah 7:9 in Greek and Hebrew

I thought BLT readers might be interested in this excerpt from Pope Francis’ first encyclical letter, Lumen Fidei (English title On Faith), released yesterday. This is paragraph 23, the first paragraph of chapter 2. (I’ve added some paragraph breaks for clarity.)

Unless you believe, you will not understand (cf. Is 7:9). The Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint translation produced in Alexandria, gives the above rendering of the words spoken by the prophet Isaiah to King Ahaz. In this way, the issue of the knowledge of truth became central to faith.

The Hebrew text, though, reads differently; the prophet says to the king: “If you will not believe, you shall not be established”. Here there is a play on words, based on two forms of the verb ’amān: “you will believe” (ta’amînû) and “you shall be established” (tē’āmēnû). Terrified by the might of his enemies, the king seeks the security that an alliance with the great Assyrian empire can offer. The prophet tells him instead to trust completely in the solid and steadfast rock which is the God of Israel. Because God is trustworthy, it is reasonable to have faith in him, to stand fast on his word. He is the same God that Isaiah will later call, twice in one verse, the God who is Amen, “the God of truth” (cf. Is 65:16), the enduring foundation of covenant fidelity.

It might seem that the Greek version of the Bible, by translating “be established” as “understand”, profoundly altered the meaning of the text by moving away from the biblical notion of trust in God towards a Greek notion of intellectual understanding. Yet this translation, while certainly reflecting a dialogue with Hellenistic culture, is not alien to the underlying spirit of the Hebrew text. The firm foundation that Isaiah promises to the king is indeed grounded in an understanding of God’s activity and the unity which he gives to human life and to the history of his people. The prophet challenges the king, and us, to understand the Lord’s ways, seeing in God’s faithfulness the wise plan which governs the ages.

Saint Augustine took up this synthesis of the ideas of “understanding” and “being established” in his Confessions when he spoke of the truth on which one may rely in order to stand fast: “Then I shall be cast and set firm in the mould of your truth”. From the context we know that Augustine was concerned to show that this trustworthy truth of God is, as the Bible makes clear, his own faithful presence throughout history, his ability to hold together times and ages, and to gather into one the scattered strands of our lives.

The NABre, the official English translation of the Bible for American Catholics, renders this part of Isaiah 7:9 as

Unless your faith is firm,

you shall not be firm!

Neither the online NABre, nor my hardcopy NAB study bible, nor my New Jerusalem bible, mention the Septuagint rendering that Francis writes of here.

Craig Fehrman reviewed in the Boston Globe Hannah Sullivan’s The Work of Revision. I have not read Sullivan’s book, so I do not know which ideas in Fehrman’s review are his own and which are Sullivan. However I do not understand the argument.

It’s easy to assume that history’s greatest authors have been history’s greatest revisers. But that wasn’t always how it worked. Until about a century ago, according to various biographers and critics, literature proceeded through handwritten manuscripts that underwent mostly small-scale revisions.

Then something changed. In a new book, The Work of Revision, Hannah Sullivan, an English professor at Oxford University, argues that revision as we now understand it—where authors, before they publish anything, will spend weeks tearing it down and putting it back together again—is a creation of the 20th century. It was only under Modernist luminaries like Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf that the practice came to seem truly essential to creating good literature. Those authors, Sullivan writes, were the first who “revised overtly, passionately, and at many points in the lifespan of their texts.”[…]

Ben Jonson, a Renaissance playwright, once observed of Shakespeare that “whatsoever he penned, he never blotted out a line.” Jonson was gently mocking the cult of Shakespeare, and it’s certainly possible that an old chest somewhere contains several radically revised versions of Shakespeare’s plays. But that seems unlikely.[…]

The problem, of course, is that we do have many variants of Shakespeare plays – e.g., the First Folio, and various Quartos for many plays. These are so different that many publishers have taken to publishing different extant versions of the plays – thus, the Norton Shakespeare, a standard college level text and anthology, publishes both the 1608 quarto text and the 1623 Folio King Lear; Arden is currently publishing Hamlet in three versions (1603, 1604, and 1623). And most Shakespeare anthologies I am aware of attempt to integrate various texts.

Now, if these do not reflect “several radically revised versions of Shakespeare’s plays,” what do they reflect?

(Fehrman-Sullivan’s theory seems to be that paper used to be expensive making revisions unlikely, and that typing forced writers to slow down so that they were able to revise. The theory as expressed in Fehrman’s review sounds unlikely to me, but again I have not read Sullivan’s book.)

“just as Shakespeare completely contorted”

“We’re very much leaving it up to the imaginations of the authors. We have talked with them about following the spirit of the plays, but it isn’t helpful for them to have to paint by numbers. We want them to bring all of their imaginations and different points of view just as Shakespeare completely contorted some of the history from which he took his own plays.”

—– Clara Farmer, Publishing Director, Chatto & Windus and Hogarth (June 26, 2013)

“I’m very drawn to American fiction and am always on the lookout for a new Marilynne Robinson or Philipp Meyer. I’m publishing a couple of fantastic American novels this coming year (The Interestings, the new Meg Wolitzer, and the new Jennifer Close, author of Girls in White Dresses), and I’d love to find a British writer to shout out about.”

—– Juliet Brooke, Senior Editor, Chatto & Windus and Hogarth (January 12, 2103)

You may already have read how American writer Ann Tyler and British writer Jeanette Winterson are the first commissioned for the re-writes of the works of William Shakespeare, a project “devised by Juliet Brooke, Senior Editor at Chatto & Windus/Hogarth, and Becky Hardie, Deputy Publishing Director [w]ith Clara Farmer, Publishing Director, … [who] comprise the UK publishing team.” Farmer says, “The time is ripe,” and she and her group are looking at 2016, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Is this Bard news specifically? Or is this rather “good news” for publishers generally, a pop “current trend for modern retellings of classic stories” as with “Val McDermid, Joanna Trollope and Curtis Sittenfeld … all currently writing reworkings of Jane Austen”?

Bard news … Anne Tyler, Shakespeare as painted in the 19th century by Leo Coblitz and Jeanette Winterson. Composite: Eamonn McCabe/Getty/Murdo Macleod

Some of us are less excited than others about the project. Is Farmer right to claim that this is driven by the spirit of Shakespeare? Are the authors’ imaginations really following the Bard? Are the historical contexts in which he writes his plays “completely contorted”?

I find Joss Whedon’s new, contemporary film version of Much Ado About Nothing to be a much more honest reworking of Shakespeare. Here he talks with Belinda Luscombe of Time magazine about his time to work with a play of the playwright he so reveres.

What are your thoughts about these new “Shakespeare” transpositions? Are they complete distortions or ways to bring the old works to new audiences?

Aristotle’s Virtue, in poetry, in translation, in prose

Theophrastus (our co-blogger) here has shared a number of wonderful books he’s picked up from the OUP 2013 Spring Sale. I’d like to begin to discuss one of them:

Aristotle as Poet: Song for Hermias and Its Contexts by Andrew L. Ford.

Fortunately, for those still considering purchasing the book from amazon.com, the online bookseller with the publisher’s permission has given a look in that allows us to focus on just a few pages, even here, together. Let me show you what Ford has brought in of the Aristotle original, and then we can look at his own translation; and then we can read a bit of Ford’s translation commentary including some his philosophy of translation here and some his understanding of the key, initial Greek word ἀρετα, or “virtue.”

Following that, I’d like to show two other earlier English translations, with a just a bit of my own commentary on them. Finally, I’d like to return to what Ford has claimed about Aristotle’s and Christians’ use of “virtue.” I believe we need to consider Ford’s statement as extreme, which as we all know Aristotle would have his disciples avoid.

Here’s what Andrew Ford has done very very well. And his entire book is really worth studying, I must exclaim! He shows us Aristotle’s poetry:

Then Ford gives us his Englishing of Aristotle’s lines:

Then Ford gives us commentary on this translating as “rather literal” as if to “follow Aristotle’s words and themes as they would have unfolded”:

Later in this post I want to come back to Ford’s claim that Aristotle’s arete is more precisely if more awkwardly to be rendered in English with the phrase “human excellence” without some alleged merely “Christian literature” meaning of “virtue” as having “moral or sexual connotations” that are allegedly “later acquired.”

For now, here are two other English translations. The first is from someone signing as “-R” and the second from Christopher North. Both can be found in the 1833 publication, Blackwood’s Edinburgh magazine, Volume 33, which begins with a section of “Greek anthology” (produced the same year in another volume), where there is the acknowledgement of some honor given to Aristotle for this poem. In particular, the mid-16th century Italian scholar Julius Caesar Scaliger is quoted making the claim that Aristotle as a poet is equal to Pindar. The two translations follow:

What is odd about these, but consistent with the Italian (neo-Roman) scholarship on the poem, is how the English uses the Roman gods’ names. Clearly, both translators find “Virtue” to be the English for Aristotle’s arete. And while “R” uses “Maid,” as does Ford, for parthene, North uses “Virgin.” This certainly begs the question of whether North is using some “Christian” understanding of the Greek or whether the apparent Victorian flair here is due to the Romanish influence.

Or perhaps Aristotle himself gives us all cause to see his arete as having “moral or sexual connotations.”

This is, in fact, the case. Let’s look at Aristotle’s own uses of the phrase in his prose.

First, what we find in general is that Aristotle makes “virtue” or “human excellence” something that is gendered, an attribute that males have in ways that females do not and cannot. For example, in Aristotle’s Rhetoric (1367a, trans. by J. H. Freese), we read:

Virtues [ἀρεταὶ] and actions are nobler, when they proceed from those who are naturally worthier, for instance, from a man rather than from a woman.

Likewise, in his Politics where Aristotle is assuming that “the male is by nature better fitted to command than the female” (1259b, trans. by H. Rackham), he asserts the following:

First of all then as to slaves the difficulty might be raised, does a slave possess any other excellence, besides his merits as a tool and a servant, more valuable than these, for instance temperance, have the courage, justice and any of the other moral virtues [ἀρετὴν], or has he no excellence beside his bodily service? For either way there is difficulty; if slaves do possess moral virtue [ἀρετή], wherein will they differ from freemen? or if they do not, this is strange, as they are human beings and participate in reason. And nearly the same is the question also raised about the woman and the child: have they too virtues [ἀρεταί], and ought a woman to be temperate, brave and just, and can a child be intemperate or temperate, or not? This point therefore requires general consideration in relation to natural ruler and subject: is virtue [ἀρετὴ] the same for ruler and ruled, or different? If it is proper for both to partake in nobility of character, how could it be proper for the one to rule and the other to be ruled unconditionally? we cannot say that the difference is to be one of degree, for ruling and being ruled differ in kind, and difference of degree is not a difference in kind at all. Whereas if on the contrary it is proper for the one to have moral nobility but not for the other, this is surprising. For if the ruler is not temperate and just, how will he rule well? And if the ruled, how will he obey well?

Clearly, Aristotle is making differentiations by gender and by class and by age, and the differences are marked in what he’s theorizing as “virtue.” Not only does Aristotle differentiate arete itself by gender, class, and age but he also makes the differences rather pronounced when discussing related concepts of character. Anne Carson, for example, observes:

The celebrated Greek virtue of self-control (sophrosyne [σωφροσύνη]) has to be defined differently for men and for women, Aristotle maintains. Masculine sophrosyne is rational self-control and resistance to excess, but for the woman sophrosyne means obedience and consists in submitting herself to the control of others.

Where Aristotle maintains the different definitions is a little later in his Politics (1260a, trans. by H. Rackham):

It is evident therefore that both must possess virtue [ἀρετῆς], but that there are differences in their virtue [ἀρετήν] (as also there are differences between those who are by nature ruled). And of this we straightway find an indication in connection with the soul; for the soul by nature contains a part that rules and a part that is ruled, to which we assign different virtues [ἀρετήν], that is, the virtue [ἀρετὰς] of the rational and that of the irrational. It is clear then that the case is the same also with the other instances of ruler and ruled. Hence there are by nature various classes of rulers and ruled. For the free rules the slave, the male the female, and the man the child in a different way. And all possess the various parts of the soul, but possess them in different ways; for the slave has not got the deliberative part at all, and the female has it, but without full authority, while the child has it, but in an undeveloped form. Hence the ruler must possess intellectual virtue [ἀρετὴ] in completeness (for any work, taken absolutely, belongs to the master-craftsman, and rational principle is a master-craftsman); while each of the other parties must have that share of this virtue [ἀρετὴ] which is appropriate to them. We must suppose therefore that the same necessarily holds good of the moral virtues [ἀρετὴ]: all must partake of them, but not in the same way, but in such measure as is proper to each in relation to his own function. [20] Hence it is manifest that all the persons mentioned have a moral virtue [ἀρετὴ] of their own, and that the temperance [σωφροσύνη] of a woman and that of a man are not the same, nor their courage and justice, as Socrates thought,but the one is the courage of command, and the other that of subordination, and the case is similar with the other virtues [ἀρετήν].

And this is also clear when we examine the matter more in detail, for it is misleading to give a general definition of virtue [ἀρετή], as some do, who say that virtue is being in good condition as regards the soul or acting uprightly or the like; those who enumerate the virtues [ἀρετὰς] of different persons separately, as Gorgias does, are much more correct than those who define virtue in that way. Hence we must hold that all of these persons have their appropriate virtues, as the poet said of woman:

“ Silence gives grace to woman” though that is not the case likewise with a man. Also the child is not completely developed, so that manifestly his virtue also is not personal to himself, but relative to the fully developed being, that is, the person in authority over him. And similarly the slave’s virtue also is in relation to the master. And we laid it down that the slave is serviceable for the mere necessaries of life, so that clearly he needs only a small amount of virtue [ἀρετῆς], in fact just enough to prevent him from failing in his tasks owing to intemperance and cowardice.

So here we begin to see how Aristotle associates arete with sophrosyne. Virtue and temperance have “moral connotations” in Aristotle long before the could have been derived from Christian senses.

Second, then, we may find Aristotle using arete with “moral and sexual connotations.” For example, only a bit later in his Politics (1263b, trans. by H. Rackham), we see this:

Selfishness on the other hand is justly blamed; but this is not to love oneself but to love oneself more than one ought, just as covetousness means loving money to excess—since some love of self, money and so on is practically universal. Moreover, to bestow favors and assistance on friends or visitors or comrades is a great pleasure, and a condition of this is the private ownership of property. These advantages therefore do not come to those who carry the unification of the state too far; and in addition to this they manifestly do away with the practice of two virtues, temperance in relation to women [δυοῖν ἀρεταῖν φανερῶς, σωφροσύνης μὲν τὸ περὶ τὰς γυναῖκας] (for it is a noble deed to refrain from one through temperance when she belongs to another) and liberality in relation to possessions (for one will not be able to display liberality nor perform a single liberal action, since the active exercise of liberality takes place in the use of possessions).

Here Aristotle is advising that men be virtuous, temperate in relations toward the opposite sex.

Now, if we turn to the New Testament and to the Greek Septuagint from which it draws the Greek phrase under discussion, then we find nothing of the moral or sexual connotations that we might find in Victorianism. There’s nothing at all of this Aristotelian prosaic connotations either. (There are six uses of the phrase in the NT and 32 in the LXX.)

In his prose, Aristotle does make his arete different for males and females and he does bring to the phrase both moral and also sexual connotations. Why would we assume that it’s devoid of such connotations in his poetry? While Andrew L. Ford gives us much insight into Aristotle’s single poem, he fails to give correct insight into its first and key word.

Cosman on Maimonides On Asthma

…Maimonides’s treatise On Asthma. Inspired by Greek texts, it was written in Arabic in the 12th century by a Jewish physician for an Islamic patron, and translated to the Western world in Latin by Christian scholars. Thanks to its remarkable style, it preserves evidence of the medieval conjunction between medical theory and actual practice. It asserts contributions of emotions to health and dramatizes the significance of diet to disease control. Incidentally, this text testifies to the venerable connection between Jewish medical practice and chicken soup.

— Madeleine Pelner Cosman, “A Feast for Aesculapius: Historical Diets for Asthma and Sexual Pleasure.” Annual Review of Nutrition, Vol. 3 (1983).

2013 Oxford University Press Spring Sale

Oxford University Press is having its 2013 Spring Sale through July 11– and has an absolutely terrible website presentation of it.

I’ve received two sets through this sale – both at 65% off and I am delighted with both of them (reviews to follow in due course):

- Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary [Edited by Christian Kay, Jane Roberts, Michael Samuels, and Irené Wotherspoon] (sale price $173, regular price $495)

- The History of Western Philosophy of Religion [Edited by Graham Oppy and Nick Trakakis] (sale price $145, regular price $415)

Today I placed an order for 18 individual volumes – more on that in a future post. (But, as readers of this blog might suspect, I did not hesitate at the chance to pick up Aristotle as Poet: Song for Hermias and Its Contexts [Andrew L. Ford, hardcover, sale price $23].)

I usually hate thesauruses (they are far too imprecise to be useful, and seem to lead readers into making serious mistakes), but I love the Historical Thesaurus. It really should be on the desk of every translator. The first volume is thematically organized with synonymous words (the Historical Thesaurus takes a much stricter view of what a synonym is than a typical thesaurus) grouped; and within each group, the words are listed in order of introduction to English. This allows translators such as Andrew Hurley to ensure that words are not anachronistic in use. It also would be a great aid to any writer of historical fiction, to ensure that characters do not speak words that were not yet invented. But most of all, it is simply fascinating to scan through – to watch a summary of the the English language’s evolution of vocabulary. (It is also quite easy to use as a thesaurus, if one wishes – the second volume contains a listing of the words in OED indexed into the first volume.) Oxford claims that this is the first (only?) historical thesaurus in any language – and I am unaware of any similar volume for English, at least.

The History of Western Philosophy of Religion appears to be a great narrative history (I cannot claim to have read all 1600 pages yet). It is modeled after Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy (which I can strongly recommend) but is multi-authored – each chapter being written by a separate author. This type of historical presentation is more pedagogically sound, I believe, than a more traditional thematic introduction (although it is inferior to reading the actual original writings.)

Note: By the way, Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy is due out as an unabridged audiobook from Naxos later this year.

Here are some other volumes on religion that looked interesting:

Greco-Roman religion:

- Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World [Edited by John G. Gager] (paperback, sale price $14)

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome [Editor-in-Chief: Michael Gagarin] (multi-volume hardcover, sale price $366)

Judaism:

- Mendelssohn: A Life in Music [R. Larry Todd] (paperback, sale price $12)

- The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion, Second Edition [Editor-in-Chief: Adele Berlin and Editorial board member: Maxine Grossman] (hardcover, sale price $68)

- The Oxford Handbook of Judaism and Economics [Aaron Levine] (hardcover, sale price $53)

Christianity:

- Architects of Piety: The Cappadocian Fathers and the Cult of the Martyrs [Vasiliki M. Limberis] (hardcover, sale price $26)

- Coptic Christianity in Ottoman Egypt [Febe Armanios] (hardcover, sale price $26)

- Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism [William Harmless] (paperback, sale price $14)

- The Resurrection of the Messiah [Christopher Bryan] (hardcover, sale price $14)

Hinduism/Buddhism/Asian:

- Classic Asian Philosophy: A Guide to the Essential Texts, Second Edition [Joel J. Kupperman] (paperback, sale price $11)

- Strong Arms and Drinking Strength: Masculinity, Violence, and the Body in Ancient India [Jarrod L. Whitaker] (hardcover, sale price $26)

- Twelve Examples of Illusion [Jan Westerhoff] (hardcover, $11)

- Yongming Yanshou’s Conception of Chan in the Zongjing lu; A Special Transmission Within the Scriptures [Albert Welter] (hardcover, $26)

Deism/Atheism/Philosophy/etc:

- Hating God: The Untold Story of Misotheism [Bernard Schweizer] (hardcover, sale price $11)

- The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism [Edited by John Greco] (hardcover, sale price $53)

- The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism [Edited by Joel Myerson, Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, and Laura Dassow ] (hardcover, sale price $53)

Blog Things: Moving On

Without getting too ambiguously punny, I want to note a couple of blog things.

First, as Theophrastus announced some time ago, google is moving on to other things and is leaving us without google reader. Anyone who uses it is advised before the month’s end Sunday, July 30, 2013 to make an archive of your things at google takeout, https://www.google.com/takeout/. If you read this blog via google reader, and want to continue with something like that, then you may also hope for something that looks and acts a bit like google reader, something like feedly, http://cloud.feedly.com, which is what I’ve switched to. And if you ever think that we blt bloggers are just moving on, then do know that we promise we will try to give you as much advance notice as the google reader people gave all of us.

Second, just in case this makes anybody feel any better, somebody (going by the name N. T. Wrong of “biblioblog” fame or infamy) recently posted at http://biblioblogtop50.wordpress.com/ to announce that “something is happening soon.” To Rod blogging at Political Jesus it meant the question of “Signs of Life for the Biblioblog Top 50?” To James blogging at Exploring Our Matrix it meant the exclamation “NT Wrong is Back!” He’d been “On The Trail Of NT Wrong” taking part in a search to uncover the real person behind the pseudonym. You can see the excitement, but it was not always like that, not for everybody. Once a blogger blogged this about the satirical blogger of the Bible (and you can infer hoped that the second would actually just move on and never come back):

What you may not know, if you care or not about any of this, is that the blog where that was first written is where the blogger wrote a post announcing “Blogging is Dead” and later said so in a follow up post where he reminisced a little (cached by google here for anybody who cares not to move on). That real live blogger about the death of blogging is David Ker, who’s been blogged about at BLT this year. (Theophrastus wrote that, although BLT’s own Suzanne at one point co-blogged with David at an other blog that’s pretty defunct now, and David guest posted at on old blog of mine once upon a time; then Suzanne, and I too, moved on to this blog, where David, of course, has only been blogged about.)

So what of that announcement that “something is happening soon”? It appears that whoever is categorizing blogs at biblioblogs and is ranking them in a or the “Complete List of Biblioblogs” has included this very blog as part of that whole in the part that is the number “1” specific category, “General Biblical Studies,” and that is 1 of the short-list “Top 20” blogs that are biblioblogs in the whole of this “Complete” list. If you care, then please go here: http://biblioblogtop50.wordpress.com/biblioblogs/. And do note the excitement and the question and the humor, before we all move on:

Criterion edition of Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah”

Criterion, arguably the best label releasing DVDs and Blu-ray disks today, this week released DVD and Blu-ray versions of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah – a nine hour plus collection of interviews about the Holocaust. There is no direct violence in the movie, but it is absolutely chilling, as Lanzmann begins to approach the sheer horror of the Holocaust.

The quality of the Blu-ray transfer certainly exceeds that of any other home video version of Shoah; and this is the most complete version because it includes three related films.:

- A Visitor From the Living (1999, 68 minutes): this was made at the same time as Shoah and discusses the Czech “model ghetto” of Theresienstadt, which was visited by the Red Cross (who failed to note that it was a cruel concentration camp).

- Sobibor – October 14, 1943, 4:00 pm (2001, 102 minutes): this was also made at the same time as Shoah and recounts the Sobibor concentration camp revolt through a long interview with Yehuda Lerner.

- The Karski Report (2010, 54 minutes): this is a follow-up on Jan Karski, one of the key subjects of Shoah.

Shoah is by far the best film I have ever seen on the Holocaust, and the scariest. The subject material is absolutely riveting and vile. At the same time, it has a slow, serious pacing (the interviews include footage of translators translating back and forth between French and Polish/Hebrew/Yiddish) that is completely unlike most contemporary documentaries. Watching Shoah is very much like reading a book, in fact. If you have never watched Shoah, I strongly commend this DVD/Blu-ray set to you. If you are able, watch it in a single day.

Lindisfarne Gospels return to the North-East

In what has to be the most hyped regional event in the English North-East, the Lindisfarne Gospels are on display in Durham – after four centuries of absence. BBC Radio 3 had an entertaining program (still downloadable from iPlayer) in which children’s novelist David Almond expresses his reactions to seeing them.

Here is Gillian Reynold’s take on the broadcast:

The Gospels Come Home (Radio 3, Sunday) was one of those documentaries you tell friends not to miss. But, let’s be frank, listening to Radio 3 on a Sunday night is not exactly the nation’s favourite pastime. Therefore I did much advance personal urging last Saturday, duly rewarded by large verbal bouquets of thanks on Monday morning. That’s why I urge anyone who missed it to find it on the BBC iPlayer.

It really was a special programme, about the return to the North East next month of the Lindisfarne Gospels, the 1,300-year-old gem of the British Library’s collection. The presenter was Tyneside-born author David Almond, whose prize-winning novel, Skellig, has been translated into 30 languages and who did the Radio 3 Anglo-Saxon Portraits essay on Caedmon.

Here, magically, he captured the unique spirit of the North East, proud, historically conscious, grimly reflective, passionately connected to landscape and language. With producer Beaty Rubens he unfolded the story of the Lindisfarne Gospels in waves of interleaved memory, reaction and fact, building with every sentence the significance of why they will soon be at Durham Cathedral.

Lindisfarne is an island in the cold North Sea. In the seventh century a small monastic community was founded there by a Northumbrian king. In 722, its Abbot, Eadfrith, died having written the text and decoration of the four Gospels. The whole community had assisted: the parchment came from the skins of 130 calves; the ink from charcoal, hawthorn, oak galls; the pens from goose feathers (from the left wing for a right-handed scribe, the right for the left handed). We know Eadfrith copied it from an Irish manuscript because there are spaces between each word. (Latin manuscripts didn’t have spaces.) The decorations embrace Lindisfarne birds, each stroke of the pen an act of devotion as Almond conjured images of “the writing season” between long dark cold winters.

In the 10th century, long after Viking raids had forced the Lindisfarne community to move inland first to Chester-Le-Street, then to Durham, another monk added an Anglo-Saxon gloss above each Latin word. To a 20th-century cradle Catholic like Almond it shines back into the Golden Age of Northumbrian art, entwining the now and then of being North Eastern.

With it in Durham, also on loan from the British Library, will be the oldest intact book in Europe, the “pocket gospel” of St John, also from the 7th century. Almond’s wonder at it, (postcard sized, original sewing intact, colours glowing) was plain. What gave this programme such impact was not its reverence for the past but its sense of how words set down long ago connect us to it. Two thousand people have already booked to go on this summer’s pilgrimage across the sands to Lindisfarne. Record numbers are expected to go to Durham. “Come and see,” said Almond. Who, after this, could resist?

I’d like to remind everyone of the convenient tool Radio Downloader for downloading BBC iPlayer programs and transcoding them to mp3.

If you are not familiar with the Lindisfarne Gospels, I can recommend this web page; or even better, Michelle Brown’s British Library book (which is only $26 if ordered from bookdepository.co.uk through a UK proxy).