The Mystery of bookdepository.com Prices

I frequently buy books from bookdepository.com. Book Depository is reasonably fast (most purchases arrive within a week), offers free shipping to pretty nearly anywhere, and features prices that are often better than Amazon. (Book Depository ships from the UK, but books are exempt from customs in the US. Unlike Amazon, they do not collect sales tax.)

However, getting the best price on Book Depository is a bit of an art. From the US, Book Depository hasat least two web sites: bookdepository.com and bookdepository.co.uk. (The latter URL will redirect you to the .com site at first. But the second time in the row ones goes to that URL, it will send you to bookdepository.co.uk .) The .com and .co.uk web sites feature significantly different prices on many books. I wish I could tell you that one web site was consistently cheaper than the other, but I have found no significant pattern.

Interestingly, I get a third set of prices when connecting through a UK proxy. Book Depository from the UK makes it easy to get pricing in $US (simply slide down the currency selection in the upper right hand corner, and pay with Paypal, for example), and the prices are often even cheaper than bookdepository.co.uk or bookdepository.com from a US IP address. Also, it turns out that many books that are listed as “unavailable” from the US web site are easily available from the UK web site.

Especially when purchasing books that are only available in UK editions or scholarly books, the pricing at Book Depository is often very attractive. I’ve generally had good service from them.

News flash: Czech Republic is not Chechnya

With news of the Boston marathon bombers being of Chechen descent, Petr Gandalovič, the Czech Ambassador to the United States, feels it is necessary to explain that the Czech Republic is not the same as Chechnya in an official statement:

As more information on the origin of the alleged perpetrators is coming to light, I am concerned to note in the social media a most unfortunate misunderstanding in this respect. The Czech Republic and Chechnya are two very different entities – the Czech Republic is a Central European country; Chechnya is a part of the Russian Federation.

Apparently, Ambassador Gandalovič does not have a very high view of American understanding of basic European geography.

Francis to open Nazi-era Pius XII files?

The Telegraph is reporting a claim by Abraham Skorka, an Argentinian rabbi and long-time friend of the new pope, that Francis will open the long-sealed Vatican files on Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli), who served as pope 1939-1958. These files may shed light on the activities of the Vatican during the Holocaust. This may solve a long-standing historical mystery regarding the Vatican’s stance during the Holocaust.

The Telegraph is reporting a claim by Abraham Skorka, an Argentinian rabbi and long-time friend of the new pope, that Francis will open the long-sealed Vatican files on Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli), who served as pope 1939-1958. These files may shed light on the activities of the Vatican during the Holocaust. This may solve a long-standing historical mystery regarding the Vatican’s stance during the Holocaust.

There are a wide variety of views of the topic (some summarized by the phrase “Hitler’s Pope”); the actual files may shed light.

Incidentally, I just today received a copy of On Heaven and Earth, the English translation of the book written by Jorge Bergoglio (Francis) and Abraham Skorka.

Minns-Parvis edition of Justin Martyr’s “Apologies”: An exemplar for presenting religious texts.

I am very impressed by the Denis Minns and Paul Parvis edition of Justin Martyr’s Apologies (part of the Oxford Early Christian Texts series). Not only is the text interesting on its own terms, but it strikes me as a model of how to present Christian religious texts (other religions, such as Judaism, have well-established models of how to present texts, e.g., Rabbinic Bibles, Vilna edition Talmud, etc).

I have long been interested in the writings of Justin Martyr (particularly his Dialogue with Trypho); but have at times faced the difficulties that all readers of Justin Martyr face: the texts have undergone obvious serious corruption. Minns and Parvis present a conservatively edited version of Apologies while still providing sufficient support to understand the work as a whole. Apologies emerges as a libellus [petition] to the emperor that includesa defense of Christianity at a time in which it was a minor religion (the efforts early Christians made to distribute their message should not be underestimated – recall Tertullian’s statement nearly a half-century later “No one comes to our books unless he is already a Christian.” (De Testimonio Animae 1):

So in the First Apology we are clearly dealing with a petition – an abnormally long one, to be sure, but still recognizably a petition. What Justin has done is to adopt the conventions of a normal libellus, but greatly to expand it by the insertion of catechetical and other explanatory material. And in so doing he has managed to hijack a normal piece of Roman administrative procedure and turn it into a device for getting his message, literally and symbolically, to the heart of the Roman world.

The core of this work is a new edited text of the Apologies in Greek and English translation. The text is heavily annotated – the Greek has a full apparatus; the English is heavily (and usefully) annotated. In addition to historical notes, textual notes, and interpretive notes, the editors also mark up the text to indicate likely lacuna in the version of the text we have.

The editors have very intelligently edited the Greek text; and this version of the Greek text is better than my previous “go to” edition edited by Miroslav Marcovich’s edition (now published in an omnibus edition with the Dialogue with Trypho). Marcovich’s edition arguably reads too smoothly (Marchovich deploying better Greek than Justin himself used!)

The question of the relationship between the so-called First Apology and Second Apology has long troubled readers; with some advocates arguing that the two apologies form one work; others arguing that the two works stand on their own, and Marcovich arguing that the Second Apology is merely an appendix to the First. Minns and Parvis persuasively argue for a “cutting-room floor” theory:

We have in the edition taken the fairly radical decision to move the last two chapters of the Second Apology (14 and 15) to the end of the First, where we think they fit quite well. We will explain in a moment the codicological considerations that led us to make that move in the first place and which, we hope, make it less temerarious than might at first appear. That leaves the Second Apology as a series of disconnected fragments, which is precisely what we believe it to be. Justin, we think, kept tinkering with his original apology, adapting it and perhaps expanding it. And he would have kept notes – perhaps a notebook – of materials excised and resources that could be deployed in street-corner or bathhouse debate – precisely the sort of debate described in the Second Apology itself in the account of his dealings with the Cynic Crescens.

That could explain why the Second Apology seems so disjointed. It could explain why there is so much overlap with and repetition from the First. It could explain why so much of the Second has an eye on hostile, philosophically minded interlocutors. And it could presence of the tale of the unnamed woman and her marital troubles. That story – so precious to us and, fortunately, to Eusebius – may have come to seem dated once the dust had settled. That would mean that, instead of being a postscript, [the Second Apology] actually contains some earlier material accumulated for use in debate. Justin, after all, must have continued to teach and debate for another ten or twelve years between the first composition of the Apology and his martyrdom. At some point the material was gathered up and published, perhaps by disciples after his death, as a monument to Justin “philosopher and martyr.”

Minns and Parvis also include full supplementary material, including a lengthy introduction explaining the history of the text and its criticism, a biography of Justin and critique of his work, and a description of the mid-second century setting of the Christian theology of the period.

All in all, this is a work that is highly accessible for the reader, while still being of strong scholarly interest. Even if one does not agree with the “cutting-room floor” theory of Minns and Parvis, one can still use this text as a guide to the apologies simply by reading the two chapters in question as part of the Second Apology rather than the First.

I have only rarely seen Christian texts presented in such a useful and serious way, with full notes, apparatus, and supplementary material. Editors would do well to emulate Minns and Parvis in stylistic approach.

How to get on TV

From the Los Angeles Times:

Aspiring astronauts and wannabe reality TV stars, take note: A nonprofit that aims to send the first human colonists to Mars by 2023 will start taking applications in July of this year.

Mars One, the Netherlands-based organization that wants to turn the colonizing of Mars into a global reality television phenomenon, is encouraging anyone who is interested in space travel to apply.

Previous training in space travel is not required, nor is a science degree of any sort, but applicants do need to be at least 18 years of age and willing to leave Earth forever.

As of now, a flight back to Earth is not part of the Mars One business model.

The problems with MOOCs 3: Homework

For an introduction to this series see here and here.

I wanted to gain some perspective on MOOCs, so I signed up to take one. The course I signed up for Gregory Nagy’s heavily hyped EdX/HarvardX course CB22x: The Ancient Greek Hero. Harvard’s Crimson reported:

I wanted to gain some perspective on MOOCs, so I signed up to take one. The course I signed up for Gregory Nagy’s heavily hyped EdX/HarvardX course CB22x: The Ancient Greek Hero. Harvard’s Crimson reported:

When CB22x: “The Ancient Greek Hero” debuts as one of edX’s first humanities courses this spring, the class will face an entirely new set of challenges than those faced by its quantitative predecessors.

CB22x, the online version of professor Gregory Nagy’s long-running course on ancient Greek heroes, will reach an anticipated audience of 40,000 when it starts this spring as part of edX, the online learning venture started by Harvard and MIT.

“Because we are a humanities course, what we need is a kind of variation of the Socratic method,” Nagy said. “Dialogue is more important than getting X amount of information uploaded at any given moment.”

Departing from the structure of his lecture course, Nagy will conduct dialogues with colleagues about the course’s assigned reading.

To encourage a more interactive experience, a technological development to facilitate private and public commentary is being developed for the class, which, according to Nagy, is the College’s longest continuously running course.

“We’re building a massive annotation tool, which will allow students to comment on any portion of course material, including video, audio, images, and text,” said Jeff Emanuel, HarvardX fellow for the study of the humanities.

[…] CB22x will focus on analyzing ancient Greek texts, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Additionally, students will have free access to the electronic version of Nagy’s new textbook, “The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours.”

“It’s not for money. It’s a labor of love,” Nagy said.

and Nagy even managed to get a plug for his course from the New York Times.

So, I signed up for the course. Now, I have read Homer in multiple English translations, and even some portions in Greek. I have even met Nagy, and I liked his book The Best of Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry, which seems to be the more sophisticated version of the material he plans to present in his course. At first glance, the course looked great. Here are some of the things that Nagy wrote on the class forum:

This is not a course in which we tell you the questions and their answers and in which you are obliged to memorize and repeat those answers to us for a "good grade" (even if you don’t really believe that they are good answers or good questions). That’s not the learning model we are using, though it may well be a fine learning model for other subjects

And Nagy explicitly excluded dogmatic statements:

The Discussion Forums have been a great success in this Course, but recently there have been some posts that convey a distinctly exclusionary message.

* "i am reading the texts and i saw many hellenic words translated wrongly and other things here is a list of the things i saw that are wrong."

* "secondly the word hora doesn’t mean quoting from the core vocab ‘season, seasonality, the right time, the perfect time’ it means only time, season in hellenic is epohi"

* "If I agree with the explanation, with which I don’t, then Zeus Will is definitely not to cause just the Iliad but the whole Trojan war, which is narrated in the previous poems (Kypria epi) and the poems after Iliad (Aithiopis, Mikra Ilias, Iliou persin etc.) that consist the Trojan epic circle."

[…] The problem here is the dogmatic tone of the statements. Assertions of dogma are not in accord with the intellectual ideals of this Class.

Humanism is an endeavor that attempts to understand how we, individually, are different from each other, and in that respect there is no single statement or belief that can be solely right or wrong. We all have different points of view, and it is these that make dialogue vital and wonderful and potentially truthful.

By careful reading of this ancient Greek poetry and literature which we are all presently reading together, we engage in a mutual endeavor toward an understanding of that culture, that is, the bronze age archaic world represented in the Homeric epics, one which is far removed from our own world.

Only by careful and delicate reading of these words can our powers of inference become successful and only then might we present our textually based arguments as part of an ongoing and unfinished discourse. If we draw upon our own particular and personal views we are simply reading ‘into’ the text: this is not the practice nor the ambition of this Course – nor of Humanism.

If we simply and overtly dismiss the interpretations of others in a quick and callous fashion, making the claim that truth is rigidly exclusive, we are not participating in the practice of dialogue and learning.

Nagy is saying all the right words. But how does the course play out in practice?

Nagy gave homework problems which went entirely against all of his noble statements.

Here was the very first problem given to students:

Who was the first to get angry in the Iliad?

* Achilles

* Agamemnon

* Neither of the two

Now, it is already a red flag that a class in humanities (particularly one with such high goals as Nagy’s class) feels it is necessary to resort to multiple choice questions. Instead, in a normal class, one would ask for an explanation of the role that anger player; or what the sources of Agamemnon’s and Achilles’s anger was, etc. But a multiple choice question?

I answered, without hesitation “Agamemnon,” since Agamemnon freely admits being the first to be angry, and of course, he had taken Chryseis as slave. But alternatively one could argue that the correct answer was Achilles, since the opening line of the poem is about the “rage of Achilles” – that is a central theme of the entire poem.

As it turns out, the only answer that the computer would accept was “Neither” – the following explanation was given:

The correct answer “Neither of those two,” because the first to get angry is Apollo, not Agamemnon or Achilles.

While that answer is defensible, it also is a trick question; and, of course, there is no opportunity for explanation here. Nagy here commits the exact offense he condemns – he gives a shallow and dogmatic assertion to what is really something of a subtle question.

The problem is not the intentions of Nagy, but rather, that the technology for the course supports only shallow interactions, when the course promises to focus on deep themes. In a normal class, this would not be an issue – in class discussion or in an essay, there is plenty of opportunity to understand deep themes. Online, there is only an opportunity to snare students in trick questions.

This experience of MOOC technology not supporting homework matching course material is typical. I’ve talked with a number of online instructors and TAs, and this point comes up over and over again. The nature of MOOC technology means that the only homework and problems that can be assigned are necessarily highly shallow. Complaints of the form: “I did all the homework, and I got 100%, but I don’t understand the lecture” seem common.

While there are any number of critiques of classroom education, in practice the classroom experience takes many different forms, developed over time to match different types of materials. A course on foreign languages is going to be different than a laboratory course on chemistry; a course on mathematics is going to be different than a course on art. And the forms of evaluation and practice are even more varied than the classroom formats. But online, everything seems to boil down to a stupefying same-ness.

Had I been required to take these sorts of online courses to earn my undergraduate degree, I am not sure I would have ever graduated.

In future posts, I hope to take up some other issues with MOOCs: including lecture formats, reading material, student motivation, social interaction, and educational balance.

It is all a giant bizarre tale unwound by UC Berkeley’s Eric Naiman. I find myself unable to describe or even to paraphrase it, except to say that it begins with an account of when Dickens met Dostoyevsky, and then takes a turn for the weird.

It is, perhaps, the oddest and even the most salacious thing printed in Times Literary Supplement in some time.

(10 July 2013: Update here)

The Straussian Maimonides

Is there a more fascinating mid-century political philosopher than Leo Strauss? He certainly ranks as an influential thinker. He left a clear mark on American conservatism. His writings have influenced an entire generation of classicists. He is closely associated with any number of repeating themes: “the theologico-political predicament of modernity,” “the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns,” “philosophy and the city,” and “the moral argument for revelation.”

If you are not familiar with Strauss’s work, Leora Batnitzky’s summary article is a great place to start.

Still, it is probably still too early to assess Strauss’s impact. There is still great division among Straussians, as indicated in the title Harry Jaffa’s brilliant Crisis of the Strauss Divided (punning on the title Jaffa’s famous book on the Lincoln-Douglas debates: Crisis of the House Divided.)

For me, two of the most interesting themes in Strauss are his:

- Discussion of esotericism in the writing of pre-modern philosophers, a theme developed in Strauss’s Persecution and the Art of Writing. By esoteric writing, Strauss is referring to writing that does not state its theme explicitly, but rather through hints and contradictions, causes a sufficiently mature reader to understand the secrets hidden in the work. In Persecution and the Art of Writing, Strauss particularly studies Maimonides, Judah Halevi, and Spinoza.

- Discussion of the difference between the Christian reception of Aristotle (as represented, for example, by Aquinas) from the Jewish reception of Aristotle (influenced by Averroes, and represented by Halevi and Maimonides). Strauss says the “Jewish Aristotelians” read Aristotle through Plato’s Laws, and thus have a Platonic perspective that the Christian reading lacks. The Jewish philosophers thus recognize the tension between “philosophy and the city.” This theme is particularly developed in Natural Right and History.

Again, Maimonides is a central figure in both of these arguments.

My first introduction to Strauss came from reading the Shlomo Pines’s English translation of Maimonides’s The Guide of the Perplexed (currently published in two volumes: 1, 2). The translation is preceded by a lengthy essay by Strauss: “How to Begin to Study The Guide of the Perplexed” in which Strauss gives evidence for his view of Maimonides as an esoteric author.

Now Kenneth Hart Green has done a great service for the reading public by collecting the complete Straussian writings on Maimonides; including writings not previously published and writings not previously available in English. (Green has a forthcoming companion book containing his own analysis entitled Leo Strauss and the Rediscovery of Maimonides, presumably a further development of the thesis Green introduced in Jew and Philosopher: The Return to Maimonides the Thought of Leo Strauss. Not also Green’s previous anthology of Straussian writings on Jewish philosophy – albeit one that does not claim to be complete.) Here are the contents of Leo Strauss on Maimonides: The Complete Writings:

- A 21-page editor’s preface, 3 page acknowledgments, and 87 page editor’s introduction, all by Green.

- Strauss’s “How to Study Medieval Philosophy,” revised from Strauss’s original manuscript (an earlier, less accurate version of the lecture appeared in The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism.)

- Strauss’s “Spinoza’s Critique of Maimonides” from Spinoza’s Critique of Religion.

- Strauss’s “[Hermann] Cohen and Maimonides” appearing in English for the first time.

- Strauss’s “The Philosophic Foundation of the Law: Maimonides’s Doctrine of Prophecy and its Sources” from Philosophy and the Law: Contributions to the Understanding of Maimonides and His Predecessors.

- Strauss’s “Some Remarks on the Political Science of Maimonides and Farabi” revised from a translation that appeared in 1990 in English translation in the journal Interpretation, and has not been previously anthologized.

- Strauss’s “The Place of the Doctrine of Providence according to Maimonides” revised from a translation that appeared in 2004 in English translation in the journal Review of Metaphysics and has not been previously anthologized.

- Strauss’s “Review of The Mishneh Torah, Book 1, by Moses Maimonides, Edited according to the Bodleian Codex with Introductions, Biblical and Talmudical References, Notes and English Translation by Moses Hyamson,” from a 1937 issue of the journal Review of Religion and has not been previously anthologized.

- Strauss’s “The Literary Character of The Guide of the Perplexed” from Persecution and the Art of Writing with revised notes.

- Strauss’s “Maimonides Statement on Political Science” is from What is Political Philosophy? with revised notes.

- Strauss’s “Introduction to Maimonides’ The Guide of the Perplexed” transcribed from tapes and appearing in print for the first time.

- Strauss’s “How to Begin to Study The Guide of the Perplexed” revised from Strauss’s introduction to Pines’s translation (also in Liberalism Ancient and Modern).

- Strauss’s “Notes on Maimonides’s Book of Knowledge” revised from a volume in honor of Gershom Scholem (also in Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy).

- Strauss’s “Notes on Maimonides’s Treatise on the Art of Logic” revised from Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy.

- Strauss’s “On Abravanel’s Philosophical Tendency and Political Teaching” revised from the essay that originally appeared in a long-out-of-print 1937 anthology.

- “Appendix: The Secret Teaching of Maimonides” which is an unpublished fragment recently found in the Leo Strauss archives at the University of Chicago.

Altogether, this is a remarkable collection, and will be of interest to anyone interested in Strauss, Maimonides, esoteric writing, or the tension between religion and philosophy.

“Despite admirable achievements from outstanding musical women in Chicago, the fact remains that women often aren’t making it onto ‘power lists’—whether informal or in print. The men in our community have been far more successful in amassing social capital and using it to advance their musical careers. Why is this the case? Why aren’t more women being recognized for visionary artistic leadership in Chicago’s contemporary music scene—and why aren’t more women providing that visionary leadership in the first place?”

—Ellen McSweeney at NewMusicBox, April 10, 2013, in response to Chicago magazine’s February “new music power list,” which included seven men and one woman

Related and Sources:

Harpist in the Lions’ Den

Blind auditions key to hiring musicians

Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of “Blind” Auditions on Female Musicians

The Point of “The Inferno”

I’m not giving anything away if you haven’t already read Deborah Copaken Kogan’s novel Between Here and April. She herself gives away a few things when responding in a recent essay to the news that her novel, The Red Book, was moved from the long list to the short list for the 2013 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

She tells the story, describing the point of The Inferno for her first novel:

It’s now 2006. I’ve just sold my first novel, Suicide Wood, a modern-day allegory of Dante’s Inferno about a mother who kills herself and her children. I’m told books with the word “suicide” in the title never sell and that I should keep my mouth shut about the Dante business: women—my novel’s alleged audience—will be turned off by Dante. And suicide. I explain that I would like women and men to read my novel, that it’s actually about suicide, and that an understanding of the Inferno is not a prerequisite for understanding it, just a bonus for Dante nerds. I remind everyone of the success of Jeff Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides. Its cover featured my friend Phyllida’s blond hair, which is how I originally came to know of the book, but I would have picked it up anyway because, though female, I’m drawn to novels about suicide. (I can’t be the only one, can I?) “His title has ‘virgin’ in it,” I’m told. My title is changed to Between Here and April. I’m not sure what this means, but I’m told, once again, I have no say in the matter.

Before telling readers about her next book (Hell Is Other Parents), the novelist has confessed, “I’m not sure what this means,” when describing the hell she has gone through with her novel. What is interesting is how she’s ended her novel. Well, she sort of ends it with “the point of The Inferno.” I told you I’m not really giving anything away to those who haven’t read it. But I do think you’ll find this letter, very close to the end of the novel, somewhat interesting, especially in light of what Copaken Kogan has revealed of her own literary story:

Samaritan Torah in English

Samaritanism is an ancient religion closely related to Judaism, but which has maintained its own version of the Pentateuch, complete with its own script and unique chant.

Samaritanism is an ancient religion closely related to Judaism, but which has maintained its own version of the Pentateuch, complete with its own script and unique chant.

The Samaritan Pentateuch has about six thousand differences from the Masoretic Pentateuch, some of them minor, but others quite significant. Interestingly, some of these variations correspond to variations also found in Septuagint or Vulgate Pentateuch.

There is a convenient parallel edition of the Masoretic and Samaritan Pentateuch in Hebrew, with the differences in boldface (the Samaritan Pentateuch is written in standard Aramaic block script). (That edition also has an appendix with the Babel story in Samaritan script and with transliterated versions of the Masoretic and Samaritan Hebrew.)

But perhaps even more exciting for the English reader, Eisenbrauns has just released an English parallel edition: English translations of the Masoretic and Samaritan versions. In this version also, differences are in bold, but some annotations are added (as well as customs related to public reading of the Samaritan text). Appendices indicate where the Samaritan version disagrees with the Masoretic text but agrees with Septuagint versions or Dead Sea Scroll versions. There are also essays by Emanuel Tov, Steven Fine, and James Charlesworth. This version looks to useful for understanding better the Samaritan Pentateuch.

But perhaps even more exciting for the English reader, Eisenbrauns has just released an English parallel edition: English translations of the Masoretic and Samaritan versions. In this version also, differences are in bold, but some annotations are added (as well as customs related to public reading of the Samaritan text). Appendices indicate where the Samaritan version disagrees with the Masoretic text but agrees with Septuagint versions or Dead Sea Scroll versions. There are also essays by Emanuel Tov, Steven Fine, and James Charlesworth. This version looks to useful for understanding better the Samaritan Pentateuch.

The editing reminds me in some ways of the Drazin-Wagner version of Onkelos Pentateuch which highlights differences between Masoretic Text and the Aramaic Targum Onkelos.

These parallel editions are incredibly useful. I would like to renew my suggestion that publishers consider the possibility of a parallel NRSV-NETS (New English Translation of the Septuagint) translation. Even better would be a four-way parallel edition that also added the Masoretic text and the Greek text, as Oxford did with its Parallel Psalter. We have also been discussing such versions in the comments to this post.

Samaritanism today is a tiny religion, with about 750 members. The group is so small that intermarriage is now problematic, and genetic defects common. These efforts, and others in Hebrew, can help to preserve at least part of Samaritan traditions.

Clive James, the seemingly ubiquitous television talk show host, Formula One commentator, Australian book critic, leukemia patient, and occasional poet and lyricist, has tried his hand at translating Dante’s Divine Comedy. And being a public sort of guy, he’s been hitting the media circuit, at least virtually.

Clive James, the seemingly ubiquitous television talk show host, Formula One commentator, Australian book critic, leukemia patient, and occasional poet and lyricist, has tried his hand at translating Dante’s Divine Comedy. And being a public sort of guy, he’s been hitting the media circuit, at least virtually.

An NPR story (with the pretentious title “Dante’s Beauty Rendered in English in a Divine ‘Comedy’”):

The Divine Comedy is also a work of literary beauty that is beyond being antiquated by time or diminished by repeated translation. The latest has been undertaken by a writer who is perhaps best known for his pointed and funny criticisms of culture. But Clive James is also a novelist, humorist, essayist, memoirist, and radio and television host […].

“I think I always wanted to translate Dante, but I always knew there was a problem,” James tells NPR’s Scott Simon. “Which is that of the three books of the Comedy — that’s Hell, Purgatory and Heaven, Hell is the most fascinating, in the first instance, ‘cause it’s full of action, it’s got a huge three-headed dog, it’s got a flying dragon, it’s got men turning into snakes and vice versa, it’s got centaurs beside a river of blood; you name it, Hell has got it. But Purgatory and Heaven have mainly just got theology. And the challenge for the translator is to reproduce Dante’s fascination with theology, which for him was just as exciting as all that action that he left behind in Hell.”

[…] Interest is what most translators lack, James adds. “They’re faithful, they’re accurate, they’re scholarly, but the actual raw poetic thrill of the verse doesn’t get through, and that’s what I think the translator must try to do if he or she can.”

James says that in order to achieve that raw poetic thrill, he first had to abandon terza rima, Dante’s preferred rhyme scheme, “which is almost impossible to do in English without strain.” English, he says, is a “rhyme-poor” language compared with Dante’s Italian. “If you’re going to do it in English, you need, I think, another approach, and I used quatrains. When I reconciled myself to that, I was off and running.”

He calls the quatrains a “nice, easily flowing rhythmic grid on which to mount the individual moments. If you can give your verse muscle, then you’re doing one of the things Dante does, because Dante has a tremendous capacity, right in the middle of the Italian language, the musicality of the Italian language, to be strong, to be vivid, to be precise. […]”

“I can say this much for sure, for certain, right here on the air,” James continues. “There is no young man’s version of this translation. I couldn’t have done it when I was younger. I had the energy, but not the knowledge, and not the knowledge of myself, because Dante is worried about himself. Dante is in a spiritual crisis, and I think you have to have been in one of your own to understand what he’s talking about. He’s seeking absolution, redemption and certainty. He’s seeking a knowledge that his life has been worthwhile. Which I still am.”

After Shakespeare, my favorite poet is Dante. My favorite novelists are Proust and Tolstoy, closely followed by Scott Fitzgerald, and perhaps Hemingway when he isn’t beating his chest. But in all my life I never enjoyed anything more than the first pieces I read by S. J. Perelman. […]

Dan Brown’s forthcoming Inferno, of which Dante will be the central subject, has already got me trembling. Brown might have discovered that The Divine Comedy is an encrypted prediction of how the world will be taken over by the National Rifle Association. When the movie comes out, with Harrison Ford as Dante and Megan Fox as Beatrice, it will be all over for mere translators. […]

My forthcoming translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy is my best book, I think […].\

From Slate (and reportedly adapted from James’s introduction to his translation):

[…] The Divine Comedy isn’t just a story, it’s a poem: one of the biggest, most varied, and most accomplished poems in all the world. Appreciated on the level of its verse, the thing never stops getting steadily more beautiful as it goes on. T. S. Eliot said that the last cantos of Heaven were as great as poetry can ever get. The translator’s task is to compose something to suggest that such a judgment might be right. […]

My wife said that the terza rima was only the outward sign of how the thing carried itself along, and that if you dug down into Dante’s expressiveness at the level of phonetic construction you would find an infinitely variable rhythmic pulse adaptable to anything he wanted to convey. One of the first moments she picked out of the text to show me what the master versifier could do was when Francesca tells Dante what drove her and Paolo over the brink and into the pit of sin. In English it would go something like:

“We read that day for delight

About Lancelot, how love bound him.”She read it in Italian:

“Noi leggevam quel giorno per diletto

Di Lancelotto, come l’amor lo strinse.”After the sound “-letto” ends the first line, the placing of “-lotto” at the start of the second line gives it the power of a rhyme, only more so. How does that happen? You have to look within. The Italian 11-syllable line feels a bit like our standard English iambic pentameter and therefore tends to mislead you into thinking that the terzina, the recurring unit of three lines, has a rocking regularity. But Dante isn’t thinking of regularity in the first instance any more than he is thinking of rhyme, which is too easy in Italian to be thought a technical challenge: In fact for an Italian poet it’s not rhyming that’s hard.

Dante’s overt rhyme scheme is only the initial framework by which the verse structure moves forward. Within the terzina, there is all this other intense interaction going on. (Dante is the greatest exemplar in literary history of the principle advanced by Vernon Watkins, and much approved of by Philip Larkin, that good poetry doesn’t just rhyme at the end of the lines, it rhymes all along the line.) Especially in modern times, translators into English have tended to think that if this interior intensity can be duplicated, the grand structure of the terzina, or some equivalent rhymed frame work, can be left out. And so it can, often with impressive results, each passage transmuted into very compressed English prose. But that approach can never transmit the full intensity of the Divine Comedy, which is notable for its overall onward drive as much as for its local density of language.

Dante is not only tunneling in the depths of meaning, he is working much closer to the surface texture: working within it. Even in the most solemn passage there might occur a touch of delight in sound that comes close to being wordplay. Still with Paolo and Francesca: in the way the word “diletto,” after the line turning, modulates into “Di Lancelotto,” the shift from “–letto” to “–lotto” is a modulation across the vowel spectrum, and Dante has a thousand tricks like that to keep things moving. The rhymes that clinch the terzina are a very supplementary music compared to the music going on within the terzina’s span.

The lines, I found, were alive within themselves. Francesca described how, while they were carried away with what they read, Paolo kissed her mouth. “Questi” (this one right here), she says, “la bocca mi basciò, tutto tremante” (kissed my mouth, all trembling). At that stage I had about a hundred words of Italian and needed to be told that the accent on the final O of “basciò” was a stress accent and needed to be hit hard, slowing the line so that it could start again and complete itself in the alliterative explosion of “tutto tremante.” An hour of this tutorial and I could already see that Dante was paying attention to his rhythms right down to the structure of the phrase and even of the word.

I have ordered a copy of this new translation, although from the preview offered on Amazon, I am not convinced that it lives up to other recent translations.

The Women’s Prize for Fiction, and why there has to be one

Deborah Copaken Kogan tells why, here.

Never delay posting

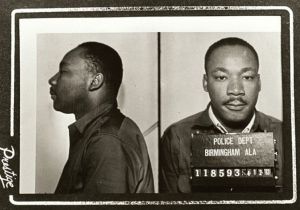

For me the moral of the Gilles Bernheim affair is that one should never delay making a blog post.

I had a lengthy post comparing the similarities, and more importantly, the differences between Bernheim and Martin King’s plagiarism.

The conclusion I was going to reach in that now-obsolete post was that King’s plagiarism was not really material to his work, but Bernheim’s plagiarism, resume-inflation, and subsequent actions was of a much more pernicious nature.

But now I need to rewrite the whole post – Bernheim, after saying he would not resign, resigned!

Moral: never delay posting.

Medieval Words for Structures of Animosity

From the fabulous Medievalists.net comes this fascinating-sounding 2001 paper by Daniel Lord Small on Hatred as a Social Institution in Late-Medieval Society. Of particular note are the words used:

At some point early in 1355, the laborer Pons Gasin of Marseilles killed a woman named Alazais Borgona. The peace act that arose from this killing does not tell us why. What it does tell us is that the killing marked the birth of a great hatred between Alazais’s kinfolk and Pons. The notary who wrote the act, Peire Aycart, had no word comparable to the German word faida and its cognates or the Italian vendetta to describe a structural relationship of animosity of this kind. Instead, he used the classical Latin word inimicitia, meaning “enmity” or “hatred,” quite literally, “unfriendship” or “unkinship.” . . . On 4 April 1355 the hostile parties met in the convent of the Augustinians of Marseilles in the presence of several leading citizens of Marseilles, and unfriendship turned to friendship as the two parties exchanged the kiss of peace and sealed the contract with a marriage.

The word inimicitia and its cognate enmitas occur frequently in the judicial records and notarial peace acts of late-medieval Marseilles, somewhat more often but in essentially the same context as two other words used to describe hatred, the classical Latin odium and the late Latin rancor. Although the semantic field covered by this quartet overlaps with another moral sentiment, namely, anger or wrath, conveyed by the words ira and furor, the two sentiments were often used in distinct ways, both in Marseilles and in other sources from the Latin Middle Ages. “Hatred,” as Robert Bartlett has pointed out, was a conventional term of medieval secular jurisprudence used to describe an enduring public relationship between two adversaries. “Anger,” in contrast, was generally used to describe a short-term and hence repairable rage, something that could break out between members of a kin group, real or fictive, who normally love one another-brothers and sisters, parents and children, lords and vassals, or God and his people. In moral literature, hatred was typically paired with love, whereas anger was paired with patience.

I’m fascinated by the notion of persistent structures of unfriendship, and by the love/hate, patience/anger pairings. I like the notion of anger as a “repairable” problem internal to a persistent relationship. It never occurred to me that these were terms relevant to jurisprudence.

New translation of “King Gesar”

Shambhala has announced that it now has for sale the first volume (out of a projected three volumes) of Robin Konrad’s long awaited translation of King Gesar (Gesar of Ling), the great epic classic of Mongolia and Tibet.

Shambhala is offering the first volume at 30% off with free shipping (with coupon code EGL413) in the US through April 30. Amazon and other commercial booksellers will not have the volume in stock until July 9.

I just ordered my copy, so I can not speak to Konrad’s translation, except to say that I’ve heard buzz about it for years. I am pretty excited.

Gesar is a vast work. Wikipedia claims that a Chinese compilation of the Tibetan versions of the epic fills over 120 volumes and a million verses; another source claims that it is twenty-five times the length of the Iliad. I am not sure that either of these claims are correct, but in any case, the Shambhala publication (which presumably will be between 2,000 and 2,500 pages in length when complete) is of a version that is longer than the Iliad, but not twenty-five times the length of the Iliad.

The Shambhala publication is not the first English adaptation, although previous adaptations in English have been much more abbreviated, and I understand that they are not really translations as much as retellings (the ones I have seen are Alexander David-Neel’s 1934 version and Douglas Pennick’s three volume [1996-2011] version [volume 1, volume 2, volume 3]; I know that there are other adaptations in English.)

Like other length epics (such as the Iliad, Odyssey, Mahabharata, Ramayana) the Mogolian-Tibetan epic King Gesar has its roots in oral recitations. One difference is that King Gesar continues to be orally recited by singers today. If you have ever seen the (highly recommended) movie Saltmen of Tibet, you will certainly recall the singer Yumen who sings from the portion of King Gesar known as “The Song of Ma Nene Karmo” (you can read a transcript of the English subtitles here).

Mircea Eliade, in his study of Shamanism, made a claim that:

Whereas “false stories” can be told anywhere and at any time, myths must not be recited except during a period of sacred time (usually in autumn or winter, and only at night).[…] This custom has survived even among peoples who have passed beyond the archaic stage of culture. Among the Turco-Mongols and the Tibetans the epic songs of the Gesar cycle can be recited only at night and in winter.

(I am not certain that Eliade’s claim is strictly true, but it is certainly evocative!)

King Gesar has had a tremendous influence on both the arts and folk art of Central Asia (see for example this collection of Tibetan thangkas retelling the King Gesar story) and the Gesar character represents a certain ideal of the magician-warrior-king. There are a number of Western art works that adapt King Gesar (notably, Peter Lieberson’s composition; which is available as a Sony recording featuring Yo-Yo Ma, Emanuel Ax, and Peter Serkin.

As I mention above, I have not yet seen the Robin Konrad translation; moreover, I am not in a position to judge it because I only know the King Gesar story from secondary sources. Still, this version comes with so much anticipation that it could very well be one of the most important translations of 2013. Here is hoping that it is good!