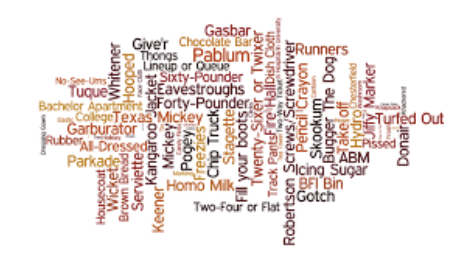

55 Canadianisms you may not know

HT Challies. I had so many perplexing moments lining up for black tea with homo milk and a serviette, while wearing a tuque and my skookum boots! There seemed to be some suggestion that I was just making all these words up. But no, here it is on the internet. I honestly find living without the Robertson screw head a real pain. I am constantly shredding threads and that just isn’t possible with a Robertson. Icing sugar. I can live without that.

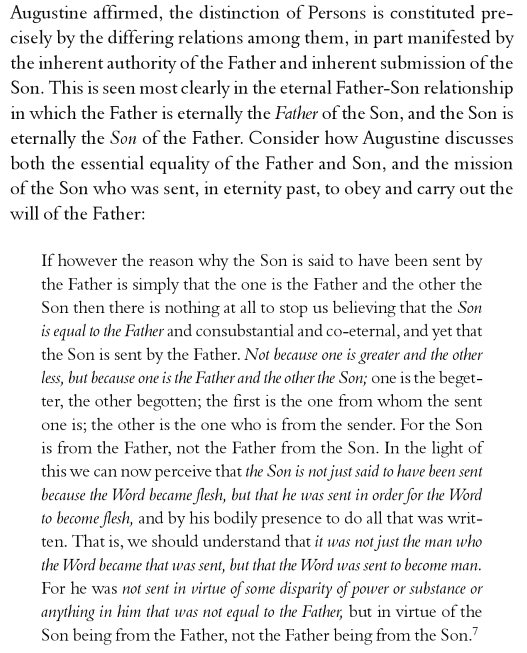

Wayne Grudem at the 2013 SBTS Theology Conference on the Trinity pt. 3

Continuing to read De Trinitate by Augustine, as I listened to Wayne Grudem and here, insist on the single working of the Father rather than on the indivisible working of the Trinity as Augustine does. Bruce Ware is relevant here because he introduced Grudem and Grudem often looked to him and referred to his presence in the audience. Ware claims the persons of the Trinity work in harmony, and not in unison, but Augustine says their working is “indivisible.”

These passages from De Trinitate Book 4: 27, English and Latin, and Book 7:12 English and Latin, make it explicit that there is no way whatsoever that the Son is less than the Father, certainly not in authority, and the passage from Ware below this will say that Augustine teachers that the Father has inherent authority and the Son has inherent submission. The Latin word for authority is potestas. Look out for what Augustine says about this.

But if the Son is said to be sent by the Father on this account, that the one is the Father, and the other the Son, this does not in any manner hinder us from believing the Son to be equal, and consubstantial, and co-eternal with the Father, and yet to have been sent as Son by the Father. Not because the one is greater, the other less; but because the one is Father, the other Son; the one begetter, the other begotten; the one, He from whom He is who is sent; the other, He who is from Him who sends. For the Son is from the Father, not the Father from the Son.

And according to this manner we can now understand that the Son is not only said to have been sent because

the Word was made flesh,but therefore sent that the Word might be made flesh, and that He might perform through His bodily presence those things which were written; that is, that not only is He understood to have been sent as man, which the Word was made but the Word, too, was sent that it might be made man; because He was not sent in respect to any inequality of power, or substance, or anything that in Him was not equal to the Father; but in respect to this, that the Son is from the Father, not the Father from the Son; for the Son is the Word of the Father, which is also called His wisdom. [sed et uerbum missum ut homo fieret quia non secundum imparem potestatem uel substantiam uel aliquid quod in eo patri non sit aequale missus est, sed secundum id quod filius a patre est, non pater a filio.]What wonder, therefore, if He is sent, not because He is unequal with the Father, but because He is

a pure emanation (manatio) issuing from the glory of the Almighty God?For there, that which issues, and that from which it issues, is of one and the same substance. For it does not issue as water issues from an aperture of earth or of stone, but as light issues from light. For the words,For she is the brightness of the everlasting light,what else are they than, she is light of everlasting light? For what is the brightness of light, except light itself? And so co-eternal, with the light, from which the light is. But it is preferable to say,the brightness of light,rather than the light of light; lest that which issues should be thought to be darker than that from which it issues. For when one hears of the brightness of light as being light itself, it is more easy to believe that the former shines by means of the latter, than that the latter shines less.But because there was no need of warning men not to think that light to be less, which begot the other (for no heretic ever dared say this, neither is it to be believed that any one will dare to do so), Scripture meets that other thought, whereby that light which issues might seem darker than that from which it issues; and it has removed this surmise by saying,

It is the brightness of that light,namely, of eternal light, and so shows it to be equal. For if it were less, then it would be its darkness, not its brightness; but if it were greater, then it could not issue from it, for it could not surpass that from which it is educed. Therefore, because it issues from it, it is not greater than it is; and because it is not its darkness, but its brightness, it is not less than it is: therefore it is equal.

Or if we choose to admit the plural number, in order to meet the needs of argument, even putting aside relative terms, that so we may answer in one term when it is asked what three, and say three substancesor three persons; then let no one think of any bulk or interval, or of any distance of howsoever little unlikeness, so that in the Trinity any should be understood to be even a little less than another, in whatsoever way one thing can be less than another: in order that there may be neither a confusion of persons, nor such a distinction as that there should be any inequality. And if this cannot be grasped by the understanding, let it be held by faith, until He shall dawn in the heart who says by the prophet,

If you will not believe, surely you shall not understand.

So we have evidence that the Son is not unequal in substance or in potestatem, which is the Vulgate translation of the Greek exousia, and therefore means in modern English Bibles, “authority.” We then read that in the Trinity, none is less than the other, “in whatsoever way one thing can be less than another.” It seems clear that the Son is not less in authority than the Father or in any other way. Ware claims that the Father has “inherent authority” and the Son has “inherent submission.” That would make them inherently different, and I don’t think Augustine would support that. I can find nothing in Augustine to support that. Remember that the Son is sent by the Father and the Son together in Augustine. Also in the Trinity, according to Augustine, there is one will and one indivisible working of all three persons.

However,in  Grudem’s presentation here, at the SBTS Theology Conference 2013, he was introduced by Bruce Ware and is in agreement with Bruce Ware on the subordination of the Son, that he is “under” the Father. So, it is important to know what Grudem believes when he talks about authority and submission. Here is an excerpt from Bruce Ware, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. (page 80 and 83)

Grudem’s presentation here, at the SBTS Theology Conference 2013, he was introduced by Bruce Ware and is in agreement with Bruce Ware on the subordination of the Son, that he is “under” the Father. So, it is important to know what Grudem believes when he talks about authority and submission. Here is an excerpt from Bruce Ware, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. (page 80 and 83)

I cannot reconcile Bruce Ware’s writing with Augustine’s De Trinitate in any way, shape or form. What am I missing? Perhaps I am missing the fact that Augustine is irrelevant, but Ware certainly quotes him as an authority.

Marvel’s Zombies Christmas Carol (graphic novel)

Charles Dickens’s horror story, “A Christmas Carol,” has seen countless adaptations in movies, stage, television, and radio. But inevitably, those adaptations focus on the heartwarming aspects of the Dickens tale, rather than the sheer fright of his masterful ghost story.

Charles Dickens’s horror story, “A Christmas Carol,” has seen countless adaptations in movies, stage, television, and radio. But inevitably, those adaptations focus on the heartwarming aspects of the Dickens tale, rather than the sheer fright of his masterful ghost story.

I recently came across Marvel’s graphic novel Zombies Christmas Carol. The hardcover edition was being remaindered at Half Price Books – if I recall correctly, I paid under $5 for it, suggesting that the publication was not particularly successful. And if so, it was a pity, because this creative adaptation manages to bring horrific aspects of Dickens to the forefront through our age’s proxy for ghosts: the zombie motif. (Remember the opening paragraph of “A Christmas Carol”? Here, that is turned on its head as Ebenezer Scrooge is visited by the undead Jacob Marley)

While the idea of adapting 19th century stories to include zombies has become rather clichéd ever since the mechanical Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, this graphic novel rises above the usual dross through the terrific (albeit gory) artwork by David Baldeon and Jeremy Treece, and the story is genuinely scary. (From Daniel Kraus’s review at Booklist: “The glossy, spectacle-laden art is uniformly fine and plenty disgusting. If you’ve ever wanted to see Tiny Tim devour his own father, you’re in luck.”)

The book is clearly commercial art, and not particularly innovative, but if you want an easy read that is free of the typical maudlin presentations of the December season, this nasty little graphic novel may be a palate cleanser.

Happy birthday Pablo!

Today would be Pablo Casal’s 137th birthday.

David Oistrakh in China 1957

On October 4th, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, launching the space race. On the same day, the Jewish Odessa-born Soviet violinist David Oistrakh and his piano accompanist Vladimir Yampolsky arrived in rainy Beijing for a grand tour of the Chinese capital, Shanghai, and Tianjin. This was the golden height of Sino-Soviet relations — Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter (and his mezzo-soprano wife, Nina Dorliak) were already in Beijing, and young Chinese musicians interested in Western music rushed to these performances of these musical giants. The official Chinese government recording company (CRC: 中国唱片总公司) quickly issued a set of eight LP “reference records” of Oistrakh’s performances in China, and they sold like hotcakes. Within a decade, at the height of the Chinese “Cultural Revolution,” those records would be destroyed as Soviets were denounced as revisionists and Western culture was forbidden.

Now, somewhat against all expectations, these recordings have been recovered, and restored in a deluxe 4CD set. I just bought a copy of these CDs, while they are not the first recordings of Oistrakh that I might recommend, they are outstanding and a fine nostalgic look at what might be considered the twentieth century’s greatest violinist.

Oistrakh’s tour was not without event (he was naturally upset when he learned that the Tupolev 104 he had flown in on crashed on its return flight to the Soviet Union, and he was “caught” listening to decadent Western jazz on Voice of America shortwave radio), it was a tremendous event that inspired an entire generation of Chinese musicians specializing in Western classical music. The Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post has an article reminiscing on Oistrakh’s tour. Sheila Melvin and Jindong Cai have a fascinating history of modern China and the effect of “classical music diplomacy” on the country entitled Rhapsody in Red: How Classical Music Became Chinese.

For me, there is another type of nostalgia associated this release – a memory of when communist governments, despite their restrictions on freedom of expression, still considered excellence in culture to be a central mission of the government. It is not a time to which I would wish to return, but it did leave us some monumental cultural achievements.

Wayne Grudem at the SBTS Theology Conference on the Trinity pt. 2

I am going to work through Augustine’s De Trinitate in sequence. I hope this will still respond to the comments made on the previous post. In Grudem’s theology, Father and Son have separate functions, God as sender, planner, initiator, director, etc. and the Son as the submissive one, and ultimately the sacrifice and victim. But this is one of my favourite all time passages from Augustine. Book 4:19, English and Latin,

19. They do not understand, that not even the proudest of spirits themselves could rejoice in the honor of sacrifices, unless a true sacrifice was due to the one true God, in whose stead they desire to be worshipped: and that this cannot be rightly offered except by a holy and righteous priest; nor unless that which is offered be received from those for whom it is offered; and unless also it be without fault, so that it may be offered for cleansing the faulty.

This at least all desire who wish sacrifice to be offered for themselves to God. Who then is so righteous and holy a priest as the only Son of God, who had no need to purge His own sins by sacrifice, neither original sins, nor those which are added by human life? And what could be so fitly chosen by men to be offered for them ashuman flesh? And what so fit for this immolation as mortal flesh? And what so clean for cleansing the faults of mortal men as the flesh born in and from the womb of a virgin, without any infection of carnal concupiscence? And what could be so acceptably offered and taken, as the flesh of oursacrifice, made the body of our priest?

In such wise that, whereas four things are to be considered in every sacrifice—to whom it is offered, by whom it is offered, what is offered, for whom it is offered,— the same One and true Mediator Himself, reconciling us to God by the sacrifice of peace, might remain one with Him to whom He offered, might make those one in Himself for whom He offered, Himself might be in one both the offerer and the offering.

This is somewhat tangential to Grudem’s presentation here, at the SBTS Theology Conference 2013, but nonetheless it is an important contribution by Augustine that deserves attention.

Wayne Grudem at the SBTS Theology Conference 2013 pt. 1

I just finished listening to this conference session, displayed below. It’s worth listening to the last 10 minutes at least. Grudem critiques the works of various Egalitarian theologians, most of which I have not read, so I can’t interact well with that aspect of his talk. But certainly, when Grudem claims that the work of God is not the work of the God and the Son, I feel an Augustine moment coming on me. In fact, I will try to post a series of selections from Augustine that seem to be at cross purposes with Grudem’s presentation.

What I am wondering is whether Augustine is now considered a heretic or has been down graded in importance or ignored, or what has happened here. Is Grudem’s thesis on the separate working of Father and Son in opposition to Augustine’s thesis of their indivisible working?

The first is from De Trinitate 2:9 English and Latin,

9. Perhaps some one may wish to drive us to say, that the Son is sent also by Himself, because the conception and childbirth of Mary is the working of the Trinity, by whose act of creating all things are created. And how, he will go on to say, has the Father sent Him, if He sent Himself?

To whom I answer first, by asking him to tell me, if he can, in what manner the Father has sanctified Him, if He has sanctified Himself? For the same Lord says both;

Say of Him,He says,whom the Father has sanctified and sent into the world, You blaspheme, because I said, I am the Son of God;while in another place He says,And for their sake I sanctify myself.I ask, also, in what manner the Father delivered Him, if He delivered Himself? For the Apostle Paul says both:

Who,he says,spared not His own Son, but delivered Him up for us all;while elsewhere he says of the SaviourHimself,Who loved me, and delivered Himself for me.He will reply, I suppose, if he has a right sense in these things, Because the will of the Father and the Son is one, and their working indivisible.In like manner, then, let him understand the incarnation and nativity of the Virgin, wherein the Son is understood as sent, to have been wrought by one and the same operation of the Father and of the Son indivisibly; the Holy Spirit certainly not being thence excluded, of whom it is expressly said,

She was found with child by the Holy Ghost.For perhaps our meaning will be more plainly unfolded, if we ask in what manner God sent His Son. He commanded that He should come, and He, complying with the commandment, came. Did He then request, or did He only suggest? But whichever of these it was, certainly it was done by a word, and the Word of God is the Son of God Himself. Wherefore, since the Father sent Him by a word, His being sent was the work of both the Father and His Word; therefore the same Son was sent by the Father and the Son, because the Son Himself is the Word of the Father.

For who would embrace so impious an opinion as to think the Father to have uttered a word in time, in order that the eternal Son might thereby be sent and might appear in the flesh in the fullness of time? But assuredly it was in that Word of God itself which was in the beginning with God and was God, namely, in the wisdom itself of God, apart from time, at what time that wisdom must needs appear in the flesh.

Therefore, since without any commencement of time, the Word was in the beginning, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God, it was in the Word itself without any time, at what time the Word was to be made flesh and dwell among us. And when this fullness of time had come,

God sent His Son, made of a woman,that is, made in time, that the Incarnate Word might appear to men; while it was in that Word Himself, apart from time, at what time this was to be done; for the order of times is in the eternal wisdom of God without time.Since, then, that the Son should appear in the flesh was wrought by both the Father and the Son, it is fitly said that He who appeared in that flesh was sent, and that He who did not appear in it, sent Him; because those things which are transacted outwardly before the bodily eyes have their existence from the inward structure (apparatu) of the spiritual nature, and on that account are fitly said to be sent. Further, that form of man which He took is the person of the Son, not also of the Father; on which account the invisible Father, together with the Son, who with the Father is invisible, is said to have sent the same Son by making Him visible.

But if He became visible in such way as to cease to be invisible with the Father, that is, if the substance of the invisible Word were turned by a change and transition into a visible creature, then the Son would be so understood to be sent by the Father, that He would be found to be only sent; not also, with the Father, sending.

But since He so took the form of a servant, as that the unchangeable form of God remained, it is clear that that which became apparent in the Son was done by the Father and the Son not being apparent; that is, that by the invisible Father, with the invisible Son, the same Son Himself was sent so as to be visible.

Why, therefore, does He say,

Neither came I of myself?This, we may now say, is said according to the form of a servant, in the same way as it is said,I judge no man.http://www.sbts.edu/resources/conferences/theology-conference-2013-session-5/

my favorite BLT posts of 9/2013

Some of my favorite bloggers are looking back at this past year on the Gregorian calendar and noting their top-read posts. I enjoy this sort of marking of superlatives, somehow aggregated as if objectively, in such a subjective way.

So maybe you’ll enjoy somewhat my little look back here at BLT blogging. I’ve compiled, in chronological order, below a very short list of posts, written in September, of 2013. I like that particular month of blogging here, most, because each and every one of us co-bloggers found the time and the inclination, then, to post:

Amos 6:1 in the LXX

Untranslatable Words which have no precise English equivalents

“Farewell NIV”?

Yom Kippur as Manifest in an Approaching Dorsal Fin

Lattimore’s Sappho, Homer, & St. Paul

Is the new Booker Prize inclusiveness a Trojan Horse?

Slight amusements

If you find yourself with a few minutes with nothing to amuse you, you may wish to try Classical FM’s “composer or pasta” quiz.

Faith, Trust, and “Miracle on 34th Street”

“Miracle on 34th Street,” as most Americans know, is a Christmas classic movie from 1947 about a department-store Santa who claims to be the real thing. I watched it again this year on Christmas night, after all the presents were opened, Christmas dinner eaten and the dishes washed.

My main contention is that defining faith as “belief without good evidence” is not only defensible in the religious context, but it’s actually implied that this is what is meant in the Christian bible, at least in some cases. . . The primary piece of scripture that an atheist appeals to which defines faith as “belief without evidence” is Hebrews 11:1 – “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.”

Christians, of course, generally deny that this verse is talking about “belief without evidence.” Their problem with understanding faith is a different one. As I discussed a few months ago in my post Saved by Being Right: Christianity and Dogmatism, Christians often approach faith as belief in the “right” doctrines — those that constitute foundational, orthodox Christianity. The ancient Athanasian Creed illustrates this approach when it says:

Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the catholic faith; which faith except every one do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt he shall perish everlastingly. . . He therefore that will be saved must thus think of the Trinity . . . This is the catholic faith, which except a man believe faithfully he cannot be saved.

Though I do hold to the Athanasian Creed, I believe it is to be read as a definitive statement of orthodox doctrine and not as a definition of faith, as faith. (And I think even the writers of this Creed would have acknowledged, when pressed, that the thief on the cross in Luke 23 was saved without believing, or even understanding, any of these things.) Despite what Counter Apologist says above about the Bible itself defining faith in terms of belief, faith is actually shown throughout the Bible to be trust in Christ, trust in God, and it is on this trust that belief is based.

Tom Gilson at Thinking Christian puts it pretty well when he quotes the Holman Bible Dictionary:

Faith in the Greek is pistis, trust. The Holman Bible Dictionary’s entry on faith (as found in Accordance 10.2) indicates that “throughout the Scriptures faith is the trustful human response to God’s self-revelation via His words and His actions.”

In other words, when Hebrews 11:1 says “Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see,” this isn’t a complete definition of faith, but a continuation of the understanding of faith as trust set forth in Hebrews 10:22-23:

Let us draw near to God with a sincere heart and with the full assurance that faith brings, having our hearts sprinkled to cleanse us from a guilty conscience and having our bodies washed with pure water. Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for he who promised is faithful.[Emphasis added.]

Faith, then, is not simply belief in certain assertions, but the assurance that those assertions can be believed, based on trust in the faithfulness of the one making the assertions. This is why the word “faith” also applies to human interactions. “Have faith in me,” a father says to his child, or a leader to her people, or a wife or husband to their spouse. “Have faith in me, and I’ll make good. Have faith in me, and I’ll keep my promise.”

So what does “Miracle on 34th Street” have to do with all this?

“Miracle on 34th Street” opens with a round, jolly, white-bearded old man correcting a department-store window decorator on his rendition of Santa’s reindeer. The old man speaks in the full confidence of apparent first-hand knowledge. His words and actions throughout the rest of the movie consistently show that he firmly believes himself to be “the one and only Santa Claus.” The mother and daughter in the movie, caught between their own pragmatic disbelief that Santa could possibly be a real person, and their face-to-face encounters with the sheer believeability of this man as Santa, eventually embrace his Claus-ness.

It isn’t that they believe without good evidence. If they are willing to see and accept it, there is good evidence that this man is who he claims to be. He says and does a number of things which are much more consistent with his being the real Santa than with him being simply a delusional old mental patient. But if they do believe, they must do so against their own common sense, against the prevailing mindset of adult society that Santa simply cannot be real. The evidence is never overwhelming, to where anyone is forced to accept him as Santa. Rather than conclusive proof, the standard of the evidence amounts to a “rational warrant.” My respected scholarly friend Metacrock describes rational warrant as follows:

Rational warrant is any logical argument that warrants a belief, or a sense of placing confidence in a proposition. Being “rational” means there are logical reasons to support it, being a “warrant” means it’s a reason to believe something. . . So the aspect of an argument that logically demonstrates a reason to believe something is a warrant. Rationally warranted belief is confidence placed in a proposition (the belief) that is well placed as demonstrated by the warrant. . . This means one [does not] need to demonstrate beyond all doubt. . . but in demonstrating the rational warrant for belief one has shown that good logical reasons allow for belief.

“Rational warrant” is the difference between belief and knowledge. No one speaks of “believing” in things that are incontrovertible fact. No one says, “I believe chickens lay eggs” or “I believe snow is cold.” Neither the audience nor the characters in the story are able to say, “I know Santa is real and this man is he.” They can only believe– or disbelieve. But we are still talking about belief, not faith. The characters have a rational warrant for belief, but they also have the contradictory force of their own pragmatism and common sense. How do they move, then, from doubt to conviction?

Their conviction comes from faith. Faith in this old man who calls himself Kris Kringle, who says he is Santa Claus. It makes no sense to them, but there is something deeply trustworthy about Mr. Kringle, and as time goes on and they get to know him better and better, they find it more and more difficult to believe that he is lying or delusional. The child finds her world opening up as she accepts Kris’s teaching in how to be imaginative and open to new possibilities. The mother finds it within herself to hope again in ideals which she had thought permanently driven out of herself by past disappointment and betrayal. And the mother’s new boyfriend finds it worth risking his career to defend Kris Kringle’s sanity to a disbelieving tribunal. In the end they all tell Kris, in one way or another, “I have faith in you.”

It is at the point of triumph that the little girl’s newfound faith is tested. It appears that Santa has not managed to get her the difficult Christmas gift she had asked for. Now, against all apparent evidence otherwise, she whispers to herself, “I believe, I believe.” Is this, then, faith showing its true colors after all? When push comes to shove, is faith really just “belief without good evidence?”

C. S. Lewis’s essay “On Obstinacy in Belief,” published in The World’s Last Night and Other Essays, addresses this issue.

To believe that God . . . exists is to believe that you as a person now stand in the presence of God as a Person. . . You are no longer faced with an argument that demands your assent, but with a Person who demands your confidence. A faint analogy would be this. It is one thing to ask in vacuo whether So-and-So will join us tonight, and another to discuss this when So-and-So’s honour is pledged to come and some great matter depends on his coming. In the first case it would be merely reasonable, as the clock ticked on and on, to expect him less and less. In the second, a continued expectation far into the night would be due to our friend’s character if we had found him reliable before. Which of us would not feel slightly ashamed if, one moment after we had given him up, he arrived with a full explanation of his delay? We should feel that we ought to have known him better.

Once she had come to know Kris Kringle, little Susan felt that it was due to her friend Mr. Kringle’s character to continue to believe that he would send her the Christmas present she asked for. It should not be considered (as Lewis puts it) “sheer insanity” that her belief was “no longer proportioned to every fluctuation of the apparent evidence.” This is because her belief was based in faith, or trust in the person of Kris Kringle– not upon a set of propositions about him, but in the man himself.

Soren Kierkegaard, who coined the term “leap of faith,” did not see it as a leap into an evidentiary abyss, or into a set of doctrines. He said:

[A]ll the individuals who are saved will receive the specific weight of religion, its essence at first hand, from God himself. Then it will be said: ‘behold, all is in readiness, see how the cruelty of abstraction makes the true form of worldliness only too evident, the abyss of eternity opens before you, the sharp scythe of the leveller makes it possible for every one individually to leap over the blade–and behold, it is God who waits. Leap, then, into the arms of God’.

Faith is a leap, yes– but it is a leap of trust. It is like a child on the edge of a swimming pool responding when her mother, in the water with arms outstretched, calls “Jump!” God is not like that mother in having a voice we can hear or arms we can see, but countless Christians through the ages, like Lewis, like Kierkegaard, have understood faith in terms of trust in Someone they have directly and personally encountered.

Faith isn’t rocket science. It doesn’t have to be. It’s more like a child meeting Santa Claus.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a story is worth a thousand pictures.

Thanks, writers of “Miracle on 34th Street.”

————————

Cross-posted from Wordgazer’s Words

*Disclaimer: I recognize that the viewpoint of this blog post is limited to the question of faith as it is set forth in Western Christianity and the secular response to the same, and doesn’t take into account the viewpoints of non-Christian religions. This should not be construed as intentional disregard of such viewpoints, but rather as simply a recognition of the limitations of my own education, understanding and perspective in dealing with this topic. Readers of other faiths are welcome to give input on their own definitions of faith in the comments.

The First “First Noel” Poem

In the Greek gospel of Luke there’s intended or unintended wordplay that hearkens to the literatures of Hesiod’s Theo-GON-y, Aristotle’s GENE-eration of Animals, and the Septuagint’s GENE-sis. The language is poetic, rhetorical, political, historical. Above all it’s Generative, GYNakatic, Birth-Womb-Earth-ish, sometimes Male-on-top sexist, other times subversively feminist.

A while back some of us looked at just Luke 2:14 (and some of us as Glorious Wordplay). This morning mainly to read aloud with my family, I had a go at more:

Dolls and train sets

I was floored to discover that little girls really do prefer dolls and pretty dresses, even if you clothe them in blue jeans and keep giving them toy trucks in their hand. There was something deeper, more ancient, more body-based in gender roles than I had realized.

I read this paragraph by a notable woman theologian and cringed. I have been reminiscing a lot about past Christmases, toys and gender. My kids seem very stereotypically their own gender to others. But I remember the little boy who stopped playing blocks to attend to his dolly, and the little girl in love with her kiddy car. I remember the years of buying Brio train sets for both children to build a bigger inventory. I remember the inclusive non-gendered toys, as well as the pretty dresses and Tonka trucks.

I remember how as a child, I spent hours lying on the floor watching my brother play with his electric train set. My sister and I spent hours with out Tinker Toy set. I remember my brothers knitting, my own children working on crafts together. Today we all hunched over a new Puzz 3D.

Let’s rewrite the quote above, “I was floored to discover that MY little girl really did prefer dolls and pretty dresses.” Well, have your own private crises, but don’t make them mine.

I won’t deny your experience of reality, but by generalizing, you deny mine. You exclude me from the group of “acceptable women.” Piffle on statements like these. Don’t deny my humanity, and I won’t deny yours. I have had enough of exclusion and shunning.

Was David a Virgin when his soul was pregnant?

Was David a Virgin when his soul was pregnant?

This is, of course, as we all would agree just a silly little question. And yet it is seriously my attempt to bring some attention to the way in Bible reading and translation we highlight gender and sex and motherliness so dogmatically. Some of my facebook friends in a particular theology group have gone on and on for hours and literally days arguing this one:

“The virgin birth, is it essential?”

Galileo said that the heart cannot rejoice in what the mind rejects. I think that millennials are going to have a harder time accepting the previous generations’ obstinate views of a faith that is contrary to science. Pew reports that 76% of Americans believe in it but only 66% of young people 18 and below.

I accept the virgin birth but I don’t think it would be a deal breaker for me if it turns out that he had an earthly father. If he did, so what? (There is that matter of NT scripture though…) Nor do I think that assent to the view is an essential part of coming to faith in God.

So, “So what?”

As Christians around the world on this fourth advent Sunday, the one before Christmas, focus on the Magnificat of the Virgin Mother Mary, I myself also recall the Magnificat in the Greek Psalms.

Here’s a bit on that from a post at another blog:

How, really, can one compare King David’s Psalm 34:1-3 and this bit of Mother Mary’s Magnificat found in Luke 1:47-49?

Well, let’s assume we really want to do that first. Okay, well then, we go to Luke’s Greek. He has her starting in like this:

Μεγαλύνει

ἡ ψυχή μου

τὸν Κύριον

Yes, her words have gender, and her words for herself and to herself and about herself are female.

My dear feminine motherly soul

Magnifies

the LORD

And yes, yes, the Roman Clementine Vulgate only makes this femininity abundantly clear, which is important, since, as we all know, Latin, like Greek, has other gender options, not only the feminine. So we hear Mary begin this way:

Magnificat

anima mea

Dominum

Mary the wo-man, of course, is not a man. S-he’s not a he. S-he, this wo-man is a fe-male, not a male.

David, of course, is a man. So let’s hear his language. In Hebrew, he starts in this way:

ביהוה

תתהלל

נפשי

The Alexandrian Jewish translator for his Septuagint renders him starting in in Greek this way:

ἐν τῷ κυρίῳ

ἐπαινεσθήσεται

ἡ ψυχή μου

Well, hmm. Well, sure. David’s word for himself, the nephesh, is a feminine noun. This is not his sex. It’s the gender of his grammar. Let’s not get carried away here. Everybody knows he has something, some body part, that Mary lacks. Maybe Luke is making his singing Mary mimic the Septuagint translator’s psalmist David. Well, hmm. They’re both feminine, the nouns that is. Psyche just does what nephesh does. It doesn’t mean, necessarily, that David’s soul, like Mary’s must be, is fe-male.

Never mind that the Roman Clementine Vulgate with its Versio Gallicana makes him saying:

In Domino

laudabitur

anima mea

Jerome is just trying to follow that Alexandrian Jewish fellow with his fancy Hellene. Yes, that’s true. They both have David continuing by saying:

Magnificate Dominum mecum

μεγαλύνατε τὸν κύριον σὺν ἐμοί

See how unclear this is? And, besides, Jerome makes David compel his fellow singers, real men of biblical manhood, to taste and see that the LORD “sweet”

(And read Suzanne McCarthy’s post here.)

know your biblical sex verbs

The writer of the Greek gospel of Matthew knew his biblical sex verbs. His intended Jewish audience knew them too. Their shared biblical knowledge signaled a sort of insider intimacy.

This worked somewhat like I’m trying to make this English blogpost work. My intended American pop culture readers will get the fact that I’m having fun. Like tv talk show host David Letterman’s “Know Your Cuts of Meat” is intended to get people involved and chuckling. My title itself is pun-funny in other ways that I won’t give away in explanation here.

I may be pretending, even, to be convicted by that thing that Robert Alter would avoid, what we all know, because of his coinage of it, as “the heresy of explanation”: “the use of translation as a vehicle for explaining the Bible rather than representing it in another language, [which] in the most egregious instances . . . amounts to explaining away the Bible.”

Alter translates Genesis 4:1 from the Hebrew to the English, as follows:

And the human knew Eve his woman and she conceived and bore Cain, and she said, “I have got me a man with the LORD.”

An earlier translator translated Genesis 4:1 from the Hebrew to the Hellene, as follows:

Αδαμ δὲ ἔγνω Ευαν τὴν γυναῖκα αὐτοῦ καὶ συλλαβοῦσα ἔτεκεν τὸν Καιν καὶ εἶπεν ἐκτησάμην ἄνθρωπον διὰ τοῦ θεοῦ

And now I’m beginning to engage with the “all kinds of questions” that Victoria (Gaudete Theology blogger and my BLT co-blogger) has raised, beginning with just these:

Kurk, how would you translate that key word ἐγίνωσκεν [in the Greek sentence of the nativity episode of the gospel of Matthew, aka Mt 1:25 – καὶ οὐκ ἐγίνωσκεν αὐτὴν ἕως οὗ ἔτεκεν υἱόν· καὶ ἐκάλεσεν τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Ἰησοῦν]?

Can we tell anything about it from its use in non-Biblical texts? What about its etymology? Is it a verb that is only ever used with a male subject, or could it equally well be used with a female subject?Linguistically, did it function as a euphemism for sex, like the English phrase “sleeping together”? Or is it a more direct word that might be used of animals as well as of people?

She asks more, and I’ll think about them for a long time. Let’s just look at these five or so.

I would translate ἐγίνωσκεν into English with scare quotes: “and he didn’t ‘know’ her until . . . ” I’d also give the readers a long footnote (to explain, like one might explain an inside joke):

The writer of the Greek gospel of Matthew knew his biblical sex verbs. (The gospel opener is political, and see this blogpost on that). The verb γινώσκω /ginóskó/ is not used for human sex or animal “generation” before its use in the Septuagint, where the Hebrew verb יָדַע /yada/ is an ambiguous verb for human sex between two individuals. If you’ll pardon my Greeky English, it’s probably a euphemism. And yet it seems to function more as a play on words. There were other Hebrew words that are biblical sex verbs. The King James translators translated this one as “know.”

(Those other phrases, different Hebrew verbs for “sex,” the KJV Englishers translated as “to lie with” and “to force” and “to love” – as in the narrative of the rape of Tamar by her brother Amnon in 2 Samuel 13. And they rendered other Hebrew phrases for sex as “to give [a daughter to]” and “to take [a wife]” and “to go into” – as in Deuteronomy 22, in the instructions regarding a virgin who’d been had sexually. Some of these biblical sex Hebrew verbs are used in combination, and so the KJV has English translations like this one for 2 Samuel 12:24 –

And David comforted Bathsheba his wife, and went in unto her, and lay with her: and she bare a son, and he called his name Solomon: and the LORD loved him.

And there are other verses with two Hebrew verbs for sex, like this one, Numbers 31:17 / 18 –

Now therefore kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman that hath known [ginóskó – LXX, yada – MT] man by lying with [koité – LXX, mishkav – MT] him.

But all the women children, that have not known [eido – LXX, yada – MT] a man by lying with [koité – LXX, mishkav – MT] him, keep alive for yourselves.

The second Greek phrase there in the verse in Numbers – κοίτη or koité – refers metaphorically to a “bed,” and its Hebrew equivalent does too. Outside of the LXX, before the Septuagint, this phrase does show up in Greek literature as a euphemism or metaphor for human sex.

But that first verb in the first verse above [i.e., in Numbers 31:17], as a Greek verb, is really Hebraic Hellene. It shows how – at least in Greek translationese – it is a verb that is not only always used with a male subject, but it could also sometimes also be more or less “equally” used with a female subject. In the verse, the female subject has “known” a male object and earns capital punishment, death.)

So this Greek verb γινώσκω /ginóskó/is a Pentateuch word. It appears in Greek Torah. It is something the writer of the gospel of Matthew would have known, and so would his readers. He includes a Tamar in his genealogy of the baby Jesus. And in the LXX Greek Genesis 38:26, there’s this Hebraic Hellene for sex –

And Judah acknowledged them, and said, She [Tamar] hath been more righteous than I; because that I gave her not to Shelah my son. And he knew [γνῶναι – gnonoai] her again no more.

Early in the Five Books of Moses translated into Hebraic Hellene, there’s Adam “knowing” Eve (and having the baby that may have been prophesied about, a foreshadowing Matthew’s readers might assume). There’s this baby, Cain, growing up and saying as an adult – in answer to where his dead murdered brother his – “I know not; Am I my brother’s keeper.” There’s Cain “knowing” his wife, and Adam “knowing” his wife again, (and the boy born may be another baby prophesied about, another foreshadowing perhaps of a second adam.)

Greek readers who didn’t know the Greek Pentateuch, the LXX, or the various Jewish Hebraic Hellene literature that grew up around it would not have really understood, wouldn’t know, all the wordplay in Matthew 1:25’s Greek verb for biblical knowing, for sex.

That’s why I’d translate ἐγίνωσκεν in Matthew 1:25 into English with scare quotes: “and he didn’t ‘know’ her until . . . “

Last Christmas

Card perfect view

From the bridge

Of the tumbling creek

between loaves of snow

But walk in those woods

Under the branches

heavy with snow

where the low grey stripped

limbs of hemlock

curl up toward

the overhanging branches

still needled and green

under their winter burden

Lichen dangles down

like grey green yarn

twisted and ready to skein

Filaments of frosted web

Hang like threads

Without ornaments

Alder cones cluster

on low bushes

orange red ash berries

pucker in the cold

The lake stretches

white with solid ice

to the other side

but open black water ripples

by the rush grown shore.

he kept her a virgin

The Virgin Mary made me nervous. When I was a child growing up in a predominantly Roman Catholic town in Massachusetts, my friends informed me that Jesus would return the same way he had come before — that is, a Jewish virgin would be his mother. Being the only Jewish virgin in the neighborhood, I might therefore become the messiah’s mother. Consequently, during much of second grade I was absolutely petrified that an angel would appear in my bedroom, say ‘Hail, Amy-Jill’, and tell me I was going to be pregnant.

— Amy-Jill Levine, opener to the “Introduction” of A Feminist Companion to Mariology

Unlike Luke’s nativity account, which emphasizes women’s active roles, Matthew’s depicts Mary as entirely passive. This presentation is consistent with Matthew’s insistence that familial connections are to be restructured in the new community that Jesus creates. Mary’s passivity serves to undercut the privileged position she acquires by being Jesus’ mother. Here, Joseph is the model of higher righteousness.

— Amy-Jill Levine, “Matthew” in the Women’s Bible Commentary

According to the Gospel, Mary maintained her virginity “until she had borne a son” (1:25)

— Amy-Jill Levine, a note a little later in her entry, “Matthew,” in the Women’s Bible Commentary

This post is a second on the Greek language of the nativity of the gospel of Matthew. I think Amy-Jill Levine makes a critically important point about the passivity (and the lesser agency) of Matthew’s virgin mother Miriam.

Take a look at what she (Levine) says in that third epigraphical quotation above here. “Mary maintained her virginity.” This is Levine’s saying what is gospel, what is according to the Gospel, what is part of verse 25 of the first chapter. I like how she (Levine) can give her (Miriam/Mary, the virgin) her own agency right in the middle of talking about how her voice and her actions are so passively portrayed in relation to men and to angels and to God Himself. Is this a slip by a woman on behalf of another woman? Or is it one person in this century giving credibility and credence to another some twenty one centuries earlier?

Well, let’s look at the Greek of 1:25 again. But first here’s how English Bible translators (mostly men translating) have rendered one phrase of that verse:

but [Joseph] kept her a virgin – NASB

But he did not consummate their marriage – NIV 2011, The Voice, The Message

But he did not have sexual relations with her – NLT, David H. Stern, New Century Version, NIV Reader’s Version, Easy-to-Read Version, N. T. Wright’s The Kingdom New Testament

knew her not – KJV, ESV, Darby, Douay-Rheims

but did not know her intimately – Holman

did not have marital relations with her – NET, GOD’S WORD®, NRSVish, William D. Mounce (2011)

didn’t know her sexually – World English Bible

—— UPDATE (to add a few more translations) —

and did not have sex with her – Ann Nyland

and did not know her as a wife – Richmond Lattimore

But he had no union with her – William D. Mounce (2006), Today’s NIV (aka TNIV), NIV 1984

but had no intercourse with her – J. B. Phillips

But he did not make love to her – NIV Reader’s Version

but they did not sleep together – Contemporary English Version, Hal Taussig’s New New Testament, V. Gilbert Beers’s One Year Bible for Children

He did not sleep with her – Funk’s, Hoover’s and The Jesus Seminar’s The Five Gospels

————-

The first one just sounds a little creepy. Now here’s how it goes in Matthew’s gospel in some texts:

καὶ οὐκ ἐγίνωσκεν αὐτὴν ἕως οὗ ἔτεκεν υἱόν· καὶ ἐκάλεσεν τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Ἰησοῦν.

One point of my post here is that there really is some latitude for women, for Mary/Miriam, for readers male and female. For the politics in the man’s world, nonetheless, Matthew’s gospel seems to have its project.

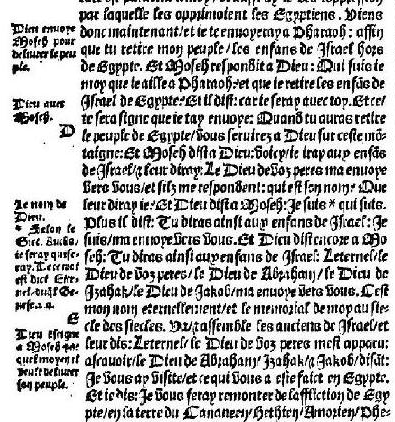

The Olivétan Bible and the Gothic Batarde font

Olivétan and the Biblia Rabbinica

I began to think that Olivétan had surely not come up with the name “Eternel” on his own. He had a library of 70 books with him as a resource. Certainly a great number for that time. In fact, when he died, he left his books to Calvin who sold them all except for the Biblia Rabbinica of Daniel Bomberg. This Hebrew Bible with Targums and commentary would have cited Maimonides. So we know that Olivétan had some exposure to Maimonides.

Maimonides, in his Guide to the Perplexed cites Targum Onkelos saying, “Eternal, Eternal, All-powerful, All-merciful, All-gracious,” with reference to Exodus 34:6. However, Olivétan does not actually use “L’Eternel” in Ex. 34:6. He does use the term in Ex. 3 but it is later French translators who used it consistently throughout the Hebrew Bible. Without a copy of the Biblia Rabbinica of Bomberg, or a list of his other books, we don’t know exactly what Olivétan had exposure to and what he had read about the use of “Eternel” for God, but probably something.

In an aside, Olivétan seems to have been a least partially responsible for the use of accents in the French language.

As Nina Catach does not exactly place Olivétan with respect to the orthographic revolution of his time, I would like to present a summary. Olivétan proposed his definition of the correct spelling in a little school manual in 1533, of which the printing is produced by Pierre de Vingle: “L’Instruction des enfans contenant la maniere de prononcer et escrire en francoys … ” He showed his concern to promote the usage of diacritics, accents aigu, grave, and circonflexe, tréma, trait d’union, apostrophe. If these signs do not appear [and they don’t usually] in the publications which he confided to Pierre de Vingle, en particular in the Bible, the fault falls to the printer. Vingle only had old materials, limited to the Gothic Batarde. In this script, not an accent, not an apostrophe, not a hyphen: the break that we mark with a comma is indicated by an oblique stroke. Dans L’Instruction of 1533, the reader is warned “You will also have to excuse the printer who has not observed the manner of writing and punctuating, by the lack of characters which he does not have at the moment.”

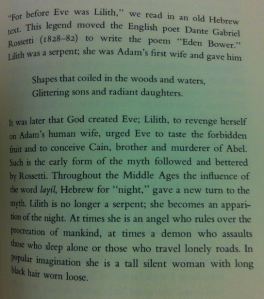

Borges and Guerrero on לִילִית

Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero together wrote a series of essays on various deities and monsters in literature. These were compiled and published in book form under titles such as Manual de zoología fantástica and El libro de los seres imaginarios. Two different English translations were produced respectively by Norman Thomas di Giovanni and by Andrew Hurley.

Borges and Guerrero likely collaborated with di Giovanni on the one English translation of the original Spanish. But “original Spanish” is open to dispute. Hurley explains this:

It it clear that for much of the material in the original Spanish [book] — sometimes entire “entries” — Borges was translating directly from a source, acknowledged in some cases, unacknowledged in many others, or was using a Spanish translation of a “classic.” Quite often, he seems to have been translating (or rewriting) into Spanish from an English translation from, for example, the Greek…. The nature of Borges’ erudition, creativity, and sense of fun is such that it has been simply impossible to ferret out all the originals, where originals in fact ever existed (some of his “quotations” are almost certainly apocrypha, put-ons)…. [My own translator notes] may make the book [in English language] seem stodgier, more academic, less fun that it was clearly always meant to be. I hope that readers of this volume [translated by me], dipping into it here and there as Borges hoped they would, will not lose (or be stripped of) their sense of playfulness by feeling that they have to go look up the page numbers for Pliny [for example] — think of it as just another of Borges’ ways of blurring lines between the serious and the playful.

I have dipped into just one entry for this particular blogpost. Below is the essay entitled “Lilith” in the Spanish and in the two respective English translations.

—-

For more on Lilith, blog readers may want to consider this BLT Blogpost written by Ann Nyland.

In addition, here is the entry in the online work, Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, written by Rebecca Lesses.