Love subjectively: translating Luke 10

This post of mine takes a rather subjective perspective. You could call it my commentary.

This morning I’m struck by what I perceive as the Greek Rhetoric influence on the gospel of Luke. And the text, its language, seems quite aware of the Hebraic construction of the Hellene of the Septuagint. Luke Chapter 10, in particular, is an example. The first pericope, or episode, has the didactic Jesus engaged in the speech-act of sending his students (disciples, learners, talmidim) out in groups. Note the number, the nod to the LXX. Within the instruction is Greek simile, Hellenic fable/parable, and Hebraic metaphors. Through the larger story, readers find allusion both to the Hebrew Bible and also to the Greek of the translation done in Alexandria, Egypt; and so there are literary hints of insider cultural coded language. There are aphorisms and there are hidden gems and there are revelations, letting the reader in on the joke, so to speak.

Then we readers come to what is famously known as the parable/fable of the good Samaritan. The Greek readers are to this point siding with the pure Jewish interlocutors, Jesus, and his talmidim apprentices, and their god, who is called (in Hellene) Kyrios. But the surprise turn in the fable/parable is that the hero is not pure racially.

The set up, rhetorically and literaturally, is the Socratic dialectic between Jesus and one of the experts in the writings of the Five Books of Moses (a Talmid Chacham, a Torah scholar). The latter questions the former first. His is a very seemingly personal question:

Διδάσκαλε, τί ποιήσας ζωὴν αἰώνιον κληρονομήσω;

Didactic-Teacher, What do I do for life on and on? What do I do to inherit that?

And so the former, in return, questions the latter. Again, it is highly personal and intensely subjective:

Ἐν τῷ νόμῳ τί γέγραπται; πῶς ἀναγινώσκεις;

In the Torah what is written? How do you read it?

The reply, the ἀπό-κρισις, the retort if you will, might seem, to us readers of Luke, to be simply only merely a direct quotation from The Shema of the Torah. At the very least, we might expect the Hebraic Hellene of the Septuagint’s version we call Deuteronomy 6.

But there’s a twist. Or a twisting. An interpreting, a changing up, an addition to what is verbatim in the Law. It’s not even the gospel writer’s clearer Greek translating of the Hebrew text, clearer than the Hellene translation of the Hebrew translators who lived before him so far away in Egypt. No, out of the mouth of the Torah scholar, this Talmid Chacham, comes a new take in Greek, with a mashup of what’s in the Hellene of Levitikus 19:

οὐ μισήσεις τὸν ἀδελφόν σου τῇ διανοίᾳ σου,

ἐλεγμῷ ἐλέγξεις τὸν πλησίον σουκαὶ οὐ λήμψῃ δι’ αὐτὸν ἁμαρτίαν.

καὶ οὐκ ἐκδικᾶταί σου ἡ χείρ,

καὶ οὐ μηνιεῖς τοῖς υἱοῖς τοῦ λαοῦ σου

καὶ ἀγαπήσεις τὸν πλησίον σου ὡς σεαυτόν·ἐγώ εἰμι κύριος.

Which roughly can be Englished this way:

thou shalt not hate that brother of yours in that mind of yours,

reproofing you shall reproof those in that near space of yoursand thou shalt not bear sin on his account

and it shall not be vengeance of yours, thine hand,

and thou shalt not be angry with the children of those people of yours,

and thou shalt love those neigh youI am kyrios [master]

Granted, the “dia-noia,” or διανοίᾳ σου, is a very good Greek translation of the Hebrew in the sense that it captures the profound subjectivity of the requirement of this law, this teaching. The prohibition against “hate” puts it in the individual, in his or her heart, or in the Hellene, deep in the mind’s thoughts.

And so when the one rabbi retorts to the other, and when that other (Jesus) validates the answer as “correct,” the translation or interpretation or hermeneutic here expressed is very, very singularly personal and very, very profoundly subjective.

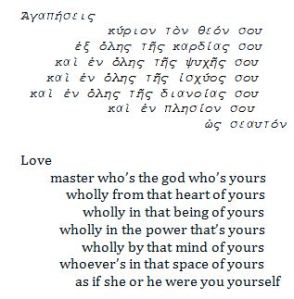

If you won’t mind, then, let me verbatim reproduce Luke’s Greek. And my English:

The universal requirement of love, and the object of that comprehensive love, wholly falls on the individual. This law, in my view, deconstructs the hierarchy of the Kyriarchy, bringing within close proximity of the Shema the additional command to love thy neighbor and in thine own mind and heart to not hate thine own brother.

Of course, Luke 10 goes on. The two rabbis get into their dialectic over “neighbor.” And didactic Jesus tells the fable that deconstructs the pure notion of the near or neigh one as a pure breed like these two pure teachers talking.

In this literary, rhetorical, fable-parable-law context, love deconstructs and love is very very subjective universally.

The best reading of the law that I have seen ever. That’s the way inside these commonly reproduced separately known ‘commandments’. O play on, Kurk … And damned be him that first cries, that’s not cricket.

Thanks so much, Bob. I was afraid too much of what and how I wrote obscured – especially since the swath of texts and the array of textuality around the commandments really needs some sort of presentation that a little blog post can’t afford. You encourage me, and your last note made me laugh out loud. 🙂