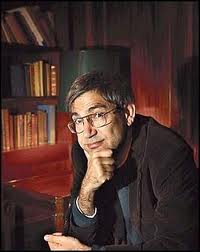

The universal dreams and ironies of Orhan Pamuk

Nobel prize winning novelist, Orhan Pamuk recently complained: “When I write about love, critics in the US and Britain say ‘this Turkish writer writes very interesting things about Turkish love’. Why can’t love be general?”

Now, is Pamuk really complaining that he wants his novels to appreciated as more generally human and less specifically Turkish? Well, at first glance it would seem that’s what he’s saying. And his fiercest critics have said this is exactly what he wants: to insult Turkish identity. After publishing his novels Kar and İstanbul: Hatıralar ve Şehir, and after these were translated into English by Maureen Freely (as Snow and Istanbul: Memories and the City) and after these were read more widely, Pamuk began receiving death threats from Turkish nationalists, who despised how his works made their Turkey look. Nonetheless, Pamuk famously spoke out and spoke up all the more, in an interview with Peer Teuwsen published in Tages-Anzeiger, the Zurich-based Swiss-German journal. And for that interview, Pamuk went on trial for having “publicly denigrated Turkish identity” — here’s where he’s commented on that in The New Yorker, as Freely translates for him again. That was June 2005, and then the world, and the world of literary scholars began to protest until, the week when the EU was to investigate the judicial system of Turkey, in late January 2006, the charges were dropped.

It’s quite clear, then, that Pamuk finds himself embraced by citizens of the world and by some of the world’s most recognized authors as one of their own. Is this the sort of “general love” that his fiction speaks of, that he’s complaining “critics in the US and Britain” are ignoring? If not officially insulting Turkish identity, then is Pamuk at least denigrating Turkish literature or Turkish culture in any way?

The answer: No.

When receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2006, he discussed with pride his Turkish heritage. At one point, he said:

Çocukluğumda, gençliğimde hissettiğimin tam tersine benim için artık dünyanın merkezi İstanbul’dur. Neredeyse bütün hayatımı orada geçirdiğim için değil yalnızca, otuz üç yıldır tek tek sokaklarını, köprülerini, insanlarını, köpeklerini, evlerini, camilerini, çeşmelerini, tuhaf kahramanlarını, dükkanlarını, tanıdık kişilerini, karanlık noktalarını, gecelerini ve gündüzlerini kendimi onların hepsiyle özdeşleştirerek anlattığım için. Bir noktadan sonra, hayal ettiğim bu dünya da benim elimden çıkar ve kafamın içinde yaşadığım şehirden daha da gerçek olur. O zaman, bütün o insanlar ve sokaklar, eşyalar ve binalar sanki hep birlikte aralarında konuşmaya, sanki kendi aralarında benim önceden hissedemediğim ilişkiler kurmaya, sanki benim hayalimde ve kitaplarımda değil, kendi kendilerine yaşamaya başlarlar. İğneyle kuyu kazar gibi sabırla hayal ederek kurduğum bu alem bana o zaman her şeyden daha gerçekmiş gibi gelir.

What I feel now is the opposite of what I felt as a child and a young man: for me the centre of the world is Istanbul. This is not just because I have lived there all my life, but because, for the last 33 years, I have been narrating its streets, its bridges, its people, its dogs, its houses, its mosques, its fountains, its strange heroes, its shops, its famous characters, its dark spots, its days and its nights, making them part of me, embracing them all. A point arrived when this world I had made with my own hands, this world that existed only in my head, was more real to me than the city in which I actually lived. That was when all these people and streets, objects and buildings would seem to begin to talk amongst themselves, and begin to interact in ways I had not anticipated, as if they lived not just in my imagination or my books, but for themselves. This world that I had created like a man digging a well with a needle would then seem truer than all else. (trans., Freely)

And he was repeating something he’d already alluded to, something that he loved as a Turk: “That lovely Turkish saying – to dig a well with a needle” (Türkçe’deki o güzel deyiş, iğneyle kuyu kazmak). So Pamuk is not, and never will be, erasing the culture, or the language, of Turkey. Rather, as he’s calling for English translations and as he’s listening to critics in English speaking nations, he’s reminding us that human dreams, that love, must be understood and experienced and given and read in literature – ironically even in great, particularly Turkish literature – as universal.

It’s hard not to love Istanbul – all my memories of Turkey from 6 weeks in 1997 are full.

That’s wonderful, Bob! (All my images are from Pamuk, from films, and from high school friends and university students from Turkey.)

And is not the US also complicit in the slaughter of the Kurds, whose rights we support in Iraq but not in Turkey? And why, after all these years, cannot we not have a serious discussion in the US government about the Armenian Genocide?

I put our 1997 Christmas letter up here – who was I then?

I always thought that what Pamuk wrote about love was universal. I love his books as a woman, and feel that he is not writing about love and life as a man or as a Turk, but as a human being in modern society.

Theophrastus,

Although the post didn’t quite bring this out, it’s precisely Pamuk’s point! Thank you very much for making clear our American complicity in the horrors of the Turkish genocide of the Armenians and the Kurds.

Bob,

Thanks again for sharing.

Suzanne,

Yes! Pamuk, a man, a Turk, speaks with all of us, of love.