King’s LiteratureS, and ours

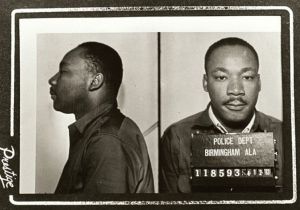

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” This week Barnett Wright, journalist and author of 1963: How the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement Changed America and the World, blogged to remind us all how Martin Luther King Jr. came “to pen what many consider a jewel of American literature.”

Because King has through the decades been accused of plagiarism, it’s important to consider the composing process for this particular letter. History records the facts of its composition particularly as a most difficult construct solely from the memory of King and mainly penned literally in the dark. (Theophrastus alludes to the alleged plagiarisms in his post here. A book length history, written perhaps as a culture wars piece itself, is Plagiarism and the Culture War: The Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr, and Other Prominent Americans by Theodore Pappas. One of the best responses from outside the King estate is Voice of Deliverance: The Language of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Its Sources by Keith D. Miller. None of this analysis examines the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” And yet, I think it is important to consider the various and varied accounts of the different versions of this letter for insights into the controversy surrounding the plagiarism accounts for King’s other writings and speeches and sermons.)

Because this letter is part of the “essay cannon” of higher education in America, it’s important to consider the material conditions under which it was composed. Let me just repeat some things here in this post that I’d observed in another:

King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” also known as “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” also known as “The Negro Is Your Brother,” has three distinct variants. I discovered this after talking with Lynn Z. Bloom by email, after she included this in her fabulous “Essay Canon.” I noticed that what Bloom included in her textbook for the canon was not the same text I had studied. But then that was to be expected. King himself published various versions for different audiences and different journals and books. And his story of how the document first came to be was not always the same. Sometimes the claim was he mainly only had jail toilet paper and old newspaper margins to write on. Other times he was not so descriptive of the detail, saying (or writing) things with more propriety like, “Begun on the margins of the newspaper in which the statement appeared while I was in jail, the letter was continued on scraps of writing paper supplied by a friendly Negro trusty, and concluded on a pad my attorneys were eventually permitted to leave me.”

Wright’s blogpost quotes “Samford University history professor Jonathan Bass [who] calls the letter the single most influential writing of the civil rights era.” Indeed, and Bass does more for all of us.

In his book, Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the “Letters from Birmingham Jail”, Bass provides the most complete account of King’s plans for the letter. This includes King’s beginning to compose it in 1962, well before he was jailed in Birmingham, well before his memory was his only source for writing, scribbling in the dark on toilet paper. The Bass account is also important because it shows very well how King’s writing was collaborative, and not just solitary as in the jail cell. The letter took a community to compose. There was planning, sharing, scribbling, writing, revising, typing, publishing, public relations, and republishing. Wyatt Tee Walker and Willie Pearl Mackey and the unnamed jailer are key persons in the composing and the publications of this important essay. This sort of community collaborative writing, I believe, is the case for much of King’s literature. It belongs to a community, even its composition. It belongs to our communities now, even its canonization as an exemplary essay, even its translation into scores of languages, even its memory half a century later.

I would like to clarify: the allegations of plagiarism against King I have read relate to his doctoral thesis. I am not aware of any allegations that he plagiarized material any of his major civil rights speeches or essays. (Of course, King freely draws on many parallels and references in those speeches and essays, but I do not view that as “plagiarism” — if it were, then writers from Shakespeare to Thomas Pynchon would be plagiarists!)

I was hoping to develop this point at length elsewhere, but here it is:

I do not think it matters that King plagiarized a portion of his doctoral thesis. King’s contribution to society did not lie in the realm of academic discourse. I think a good case can be made that King perhaps did not deserve his Ph.D. (although a Boston University committee found that despite his plagiarism that it would not revoke his doctoral degree because the dissertation made “an intelligent contribution to scholarship.”) However, King was not a professor or an academic; and his academic achievements are not relevant to King’s central messages.

Gilles Bernheim, who held the chief rabbi position in France, tried to make a similar argument when his plagiarism and resume-inflation was discovered; reportedly claiming “I have not committed fault in the exercise of my functions. To resign would be an act of vanity and desertion.”

However, I think that Bernheim was in the wrong. First, Bernheim clearly did rely on his resume inflation to achieve his post as chief rabbi; further, Bernheim’s plagiarism was in a pastoral work that was published during his tenure as chief rabbi. Thus, Bernheim did, contrary to his statement, commit plagiarism in the exercise of his functions. Further, Bernheim went on the attack; accusing other of plagiarizing his works, denying the resume inflation, and acting intellectually dishonestly under press scrutiny. In other circumstances, this may have been forgivable, but not for a chief rabbi — Bernheim committed an offense called in Jewish law a chillul Hashem.

—————————–

Let me take another example to sharpen my point — comparing King to Clarence Thomas.

Some people have claimed that King had sexual affairs — if these allegations are true, I do not see how they bear on King’s main contribution as a civil rights activist. I am unaware of any allegations that King ever engaged in harassment or other non-consensual, predatory behavior.

But, I object most strongly to Clarence Thomas’s appointment to the Supreme Court. We properly expect a higher standard for judges; all the more for those serving on the highest US court. The evidence is overwhelming that Thomas committed sexual harassment against Anita Hill; even worse, the evidence is strong that he lied about it under oath. I might be inclined to forgive such behavior in ordinary citizen, but not to someone who is given the role of being a high judge.

… a Boston University committee found that despite his plagiarism that it would not revoke his doctoral degree because the dissertation made “an intelligent contribution to scholarship.”

…. King was not a professor or an academic

…. his academic achievements are not relevant to King’s central messages

Theophrastus,

You point to why it does not, or perhaps should not, matter that King plagiarized his dissertation. He is not an academic, at least not in the senses that more narrowly the largely white academy of his day would define that.

Keith Miller similarly argues that the plagiarism really does matter to King’s theology perhaps but definitely to his delivery, both his message and that very strong communal and yet deeply distinct voice. Miller contends how it matters as a point of difference between the merely academic and the largely rhetorical, a difference between the ivory tower and the African American pulpit:

An amazon reader reviewer, who self-identifies without any reference to his own race (but rather as an award winning journalist) and who redirects the readers of his reviews to his various blogs (including one with the subtitle: “Chronicling Black Supremacism Since 1990”), protests the following:

It’s important to respond. Miller points his own readers to King’s uses of words. These words are not hidden away from the public and are probably some of the most scrutinized and remembered words in the history of the Civil Rights conflict in particular and of the United States in general. The allegations of plagiarism can be proven true in some cases — and Miller of course, even in the brief excerpts I’ve quoted above, does concede that King’s dissertation plagiarized. So Miller’s point is not that King or “that blacks cannot commit plagiarism.” Miller’s point is not that “voice merging” is some sort of sophism that receives a pass on the claims of intellectual property rights as a squatter might claim the right to sit on somebody else’s front yard. Rather, we are asked by Miller, especially white intellectuals and academics like himself are asked by Miller, to read and to listen to what King wrote and what he said. And how he used language.

If this amazon reviewer who works for his “Chronicling” is really interested in correct statements of “the black … tradition,” then he would do well to read Toni Morrison’s essay, in an important book by the same title, “Playing in the Dark.” She starts in by declaring:

Morrison’s thesis, if an excerpt suffices, is the following:

What Morrison does is to look at “whiteness” in American literature, as it trends in academic writings by whites as if “original,” as if unplagiarized. It responds, she contends, invariably to the presence of blackness. This, I would argue, is what the would-be raceless self-promoting award-winning journalist writing as “Chronicling Black Supremacism Since 1990” is found doing, even in his misreading of Keith Miller’s study of the rhetorics of Martin Luther King, Jr. The profound thing here, something both King and Morrison do with their own words, is that they do not allow the white majority in the United States, even in the academy or in journalism or in amazon.com reader reviews, to ignore the fact that they are only pretending to ignore their own uses of the African American minority among them. If we listen and read carefully, whoever we are and whatever our constructed race in society, then we see some profound irony in the definitions of and especially the real practices of “plagiarism.”

Morrison’s book looks interesting, but I do not understand your reference to the essay with “the same title” — you mean the first chapter of her book (“Black Matters”), right?

Yes, Morrison’s first chapter (actually a lecture transpositioned and transcribed as an essay on literary criticism) is entitled, “Black Matters.” That was an unnecessary mistake of mine to write what I did — writing way too quickly I’m afraid. Morrison, of course, is playing with the word “play” in this first chapter. And she turns it around on “white” unmarked majority literature, the word as if there’s a childlike “playing.” (Not long after this lecture was published, she lectures now as the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature of 1993, on a very similar theme — her wordplay much more obviously dealing, as a parable, with tricky children trying to trick the wise, except “In the version I know [she asserts] the woman is the daughter of slaves, black, American, and lives alone in a small house outside of town.” And she runs through images of the ostensible insignificance of “the woman … black” when setting up what she knows, and what she must watch though blind — even children playing on a playground: “The old woman is keenly aware that no intellectual mercenary, nor insatiable dictator, no paid-for politician or demagogue; no counterfeit journalist would be persuaded by her thoughts. There is and will be rousing language to keep citizens armed and arming; slaughtered and slaughtering in the malls, courthouses, post offices, playgrounds, bedrooms and boulevards; stirring, memorializing language to mask the pity and waste of needless death.”) I really didn’t mean to digress so much here. “Playing” is such a theme for Morrison, and in “Black Matters” in Playing in the Dark, she says and writes:

—

As an unrelated pr perhaps related aside, some of the African American literary critics I know have been engaged in a social media conversation around the American media’s stereotypes for the two suspects in the recent Boston Marathon bombings. At first there was suspicion that these individuals were “dark-skinned or black.” When it became clear that these were rather not African, not Middle Eastern, not South or East or Southeast Asian, not Hispanic but were European, if East European and, of course, Muslim, radicals, there was no reporting of their whiteness. Only the FBI posters listed their race as white, but the media reports did not use “white” to describe them. The surprise, instead, reported regularly was/ is how “American” they looked and acted, how regular, normal, like the rest of us.

It would certainly be interesting to study the relative impact of racial vs religious stereotypes when it comes mental images of terrorism. When we think of “Beltway snipers” Lee Boyd Malvo and John Allen Mohammad, for example, do we first think of their race or their religion?

Interesting examples. We might add to the list John Walker Lindh, Timothy McVeigh, Ted Kaczynski, and Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris.

Here’s a fascinating blogpost related to our comments so tangential to this post.

Right — those names are clearly perceived as nut-cases — political opponents from the extreme right or left (so we view them as radical extremists). They don’t match any religious or racial categories, so they fall into the “political category.”

I don’t think that is what is happening with Malvo and Mohammad, though. I think most people think of them first as “Black” or “Muslim,” because that is how they were characterized by the media, and that also fits some preconceptions borne from our stereotypical views of “Blacks” and “Muslims.”

I guess the question I am wondering is which adjective comes to mind first for most people. In other words, if I asked the random person “give me a list of adjectives describing Malvo and Mohammad” I wonder which would appear higher in the list: terms describing race or terms describing religion.

By the way, I finally got a copy of Pappas’s book. It is a very odd book and racist, which deserves full comment on its own. My surprise (which I will elaborate on later) is that such a book managed to to get the blurbs it did.

It does not surprise me that Pappas’s fellow-paleoconservative Barry Gross wrote a blurb, but I was a bit shocked to realize that Jacob Neusner and John Lukacs had written blurbs for it — I thought they had more sense.

Thanks for your comments. I’m especially grateful for your assessment of Pappa’s book and of Neusner’s an Lukacs’s blurbs. Any who would read it would do as well to consider Keith Miller’s book as giving a much needed response and a studied understanding of the rhetorics of MLKJr.

On race and religion and alleged terrorists and their profiles, did you see this? In his comment responding to the Huffington Post article announcing his arrest for building bombs, Mykyta Panasenko self identifies this way:

“White (caucasian). Religiously, I suppose I am Christian if I am anything, but I haven’t been to church for a long time, though still keep a Bible on my bookshelf.”

Whiteness and Christianity and the possession of the Bible (vs. their respective opposites) are used to calm the public.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/04/25/mykyta-panasenko-arrested_n_3158241.html

If I get a chance, I’ll post a full review of Pappas’s book. It is full of animus.

On another topic, I am wondering if you saw this article (or Rieder’s books): http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/15/us/martin-luther-king-jr-sermons.html

Theophratus,

Sorry to reply so late. No, I hadn’t seen the article nor have I read Rieder’s newest book mentioned in it. But did you see this article in the nytimes written earlier in the year, by Rieder himself, where he gives an interpretation of the intent of MLK Jr: